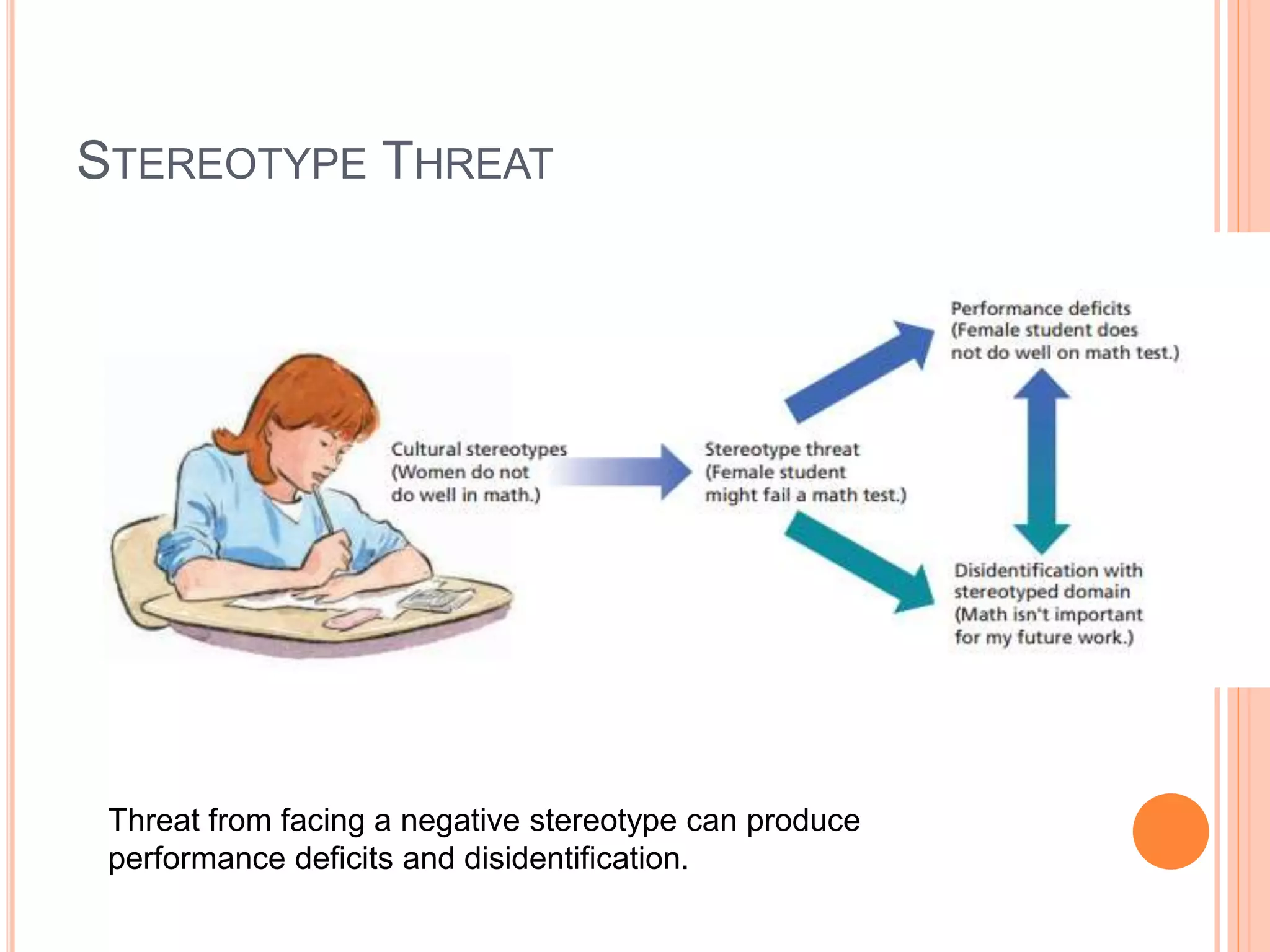

Prejudice and stereotypes are self-perpetuating and can bias our judgments of individuals. Stereotypes guide our attention and memories in ways that confirm our existing biases. They can also become self-fulfilling prophecies that affect victims' outcomes. Stereotype threat occurs when facing a negative stereotype undermines performance due to stress and worrying about confirming the stereotype. Strong stereotypes particularly color our judgments when information about people is limited.