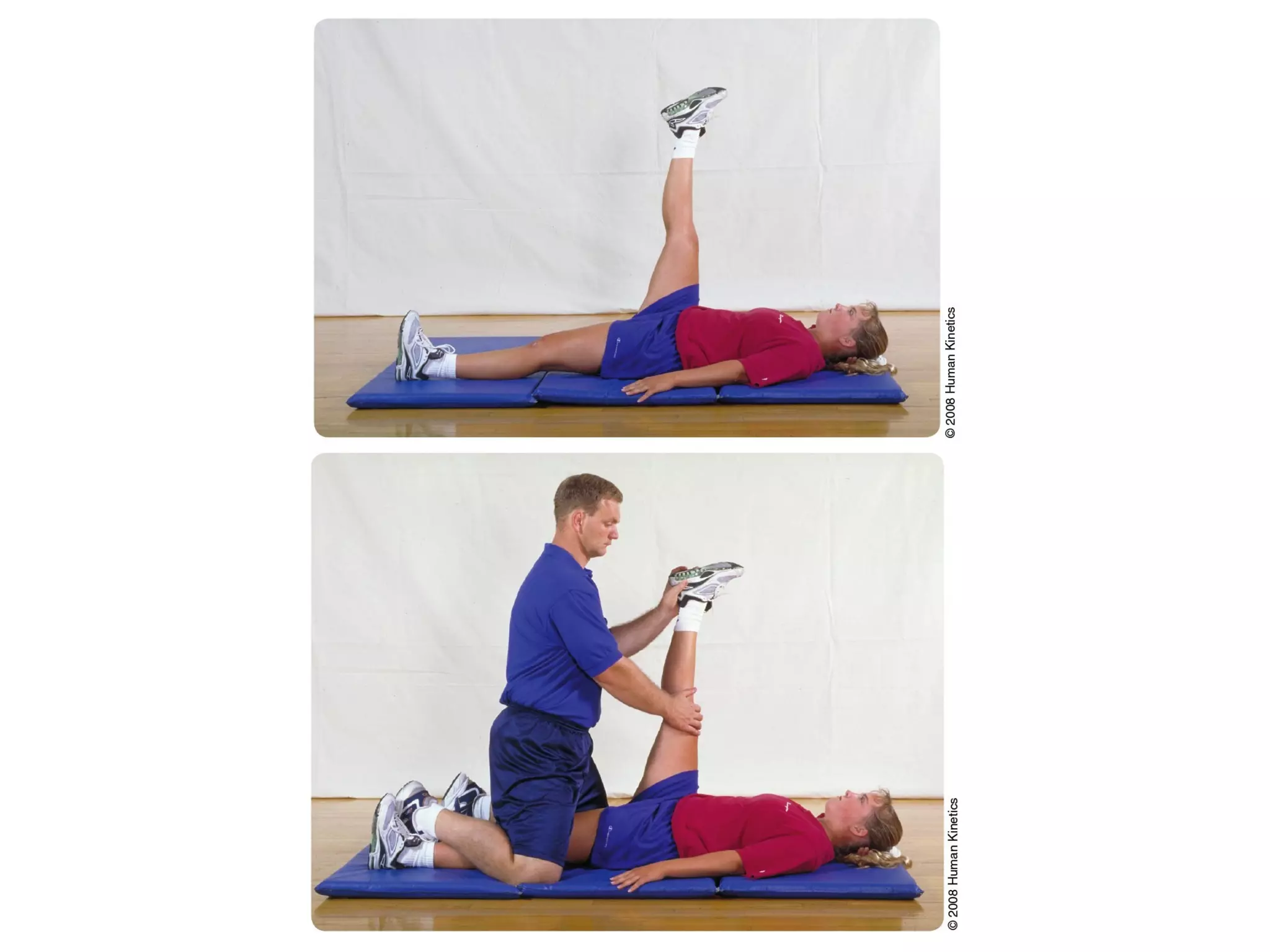

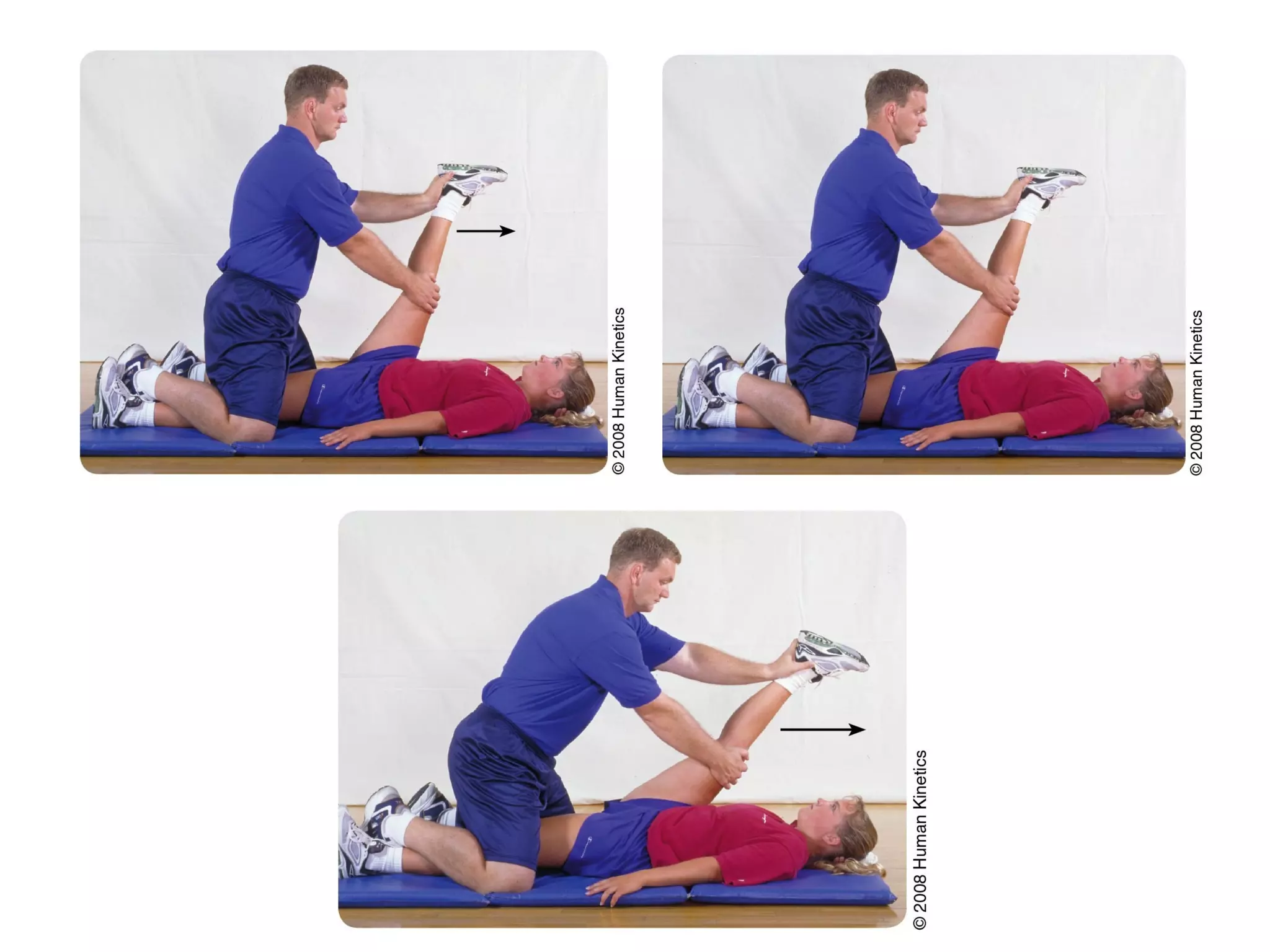

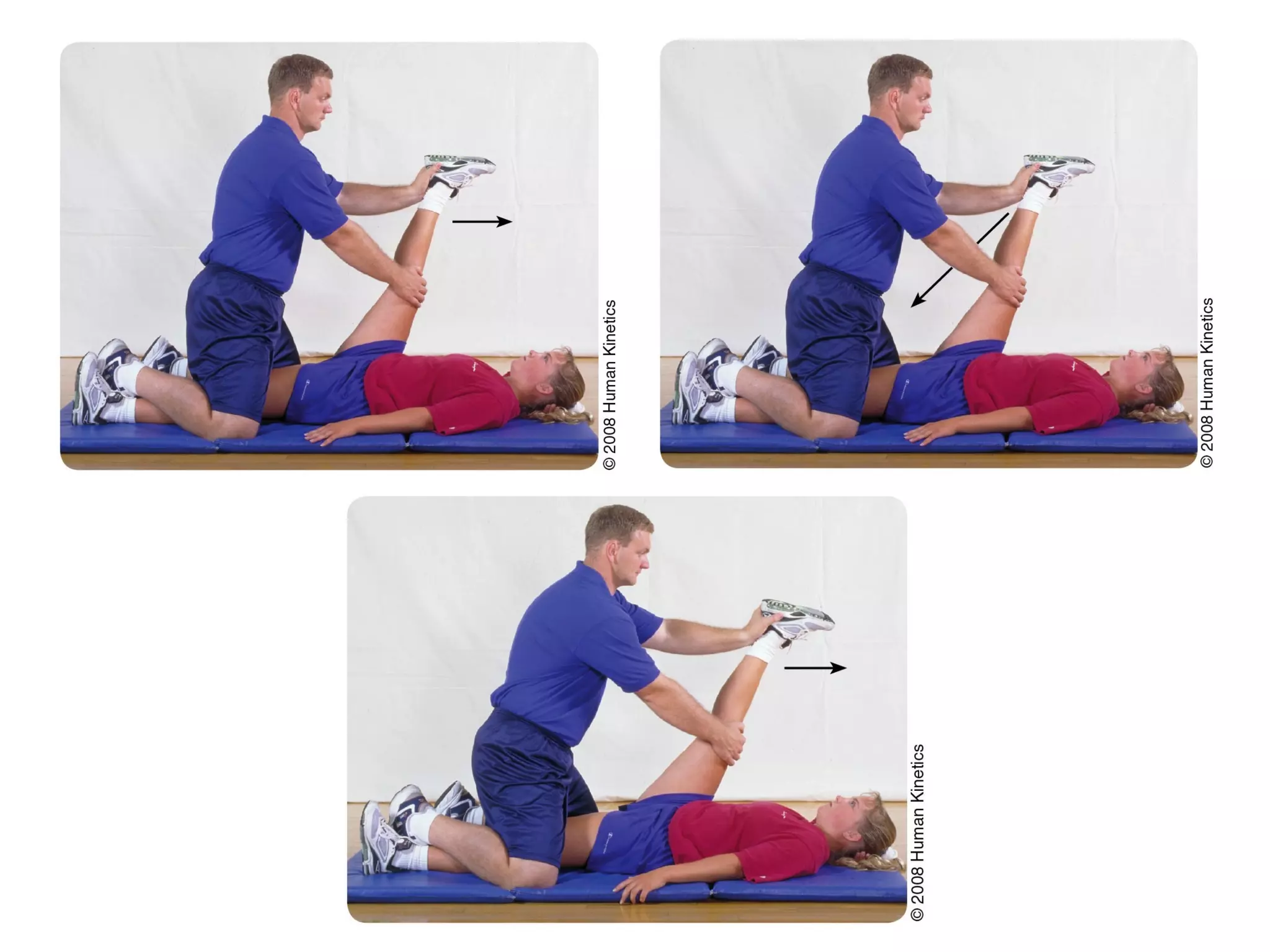

This document discusses warm-up and stretching. It defines warm-up as activities that increase muscle temperature and blood flow, improving performance. An effective warm-up has general and sport-specific components lasting 5-12 minutes. Stretching is most effective post-exercise and should involve dynamic motions. Flexibility depends on factors like age, sex, activity level and can be improved through regular stretching, especially PNF techniques using partner assistance or agonist muscle contraction. Guidelines are provided for static, dynamic and PNF stretching techniques.