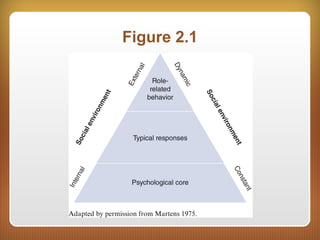

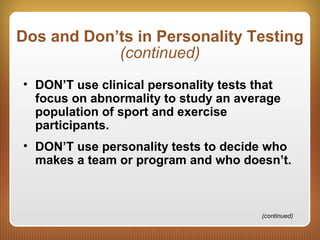

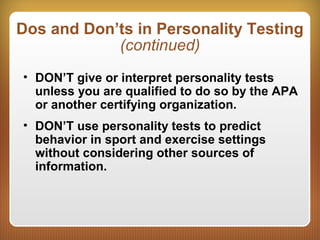

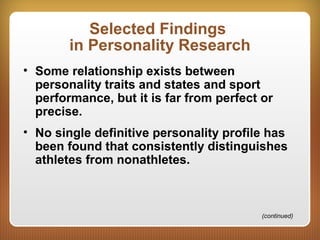

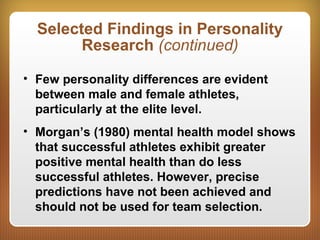

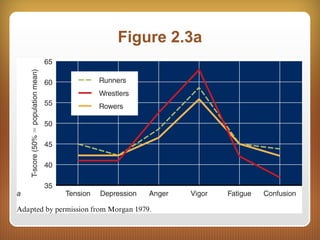

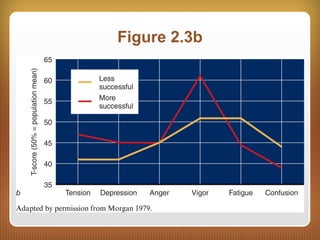

This document discusses personality and its relationship to sport performance. It defines personality and outlines several approaches to understanding it, including the psychodynamic, trait, situational, interactional, and phenomenological approaches. Research support for each approach is provided. The document also discusses measuring personality, selected findings in personality research related to sport, cognitive strategies and their link to athletic success, and guidelines for the reader's role in understanding personality.