1) The document discusses vascular anomalies, specifically infantile hemangiomas.

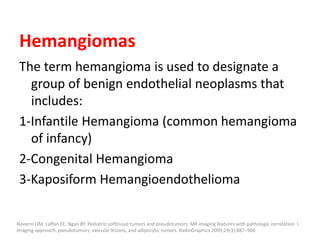

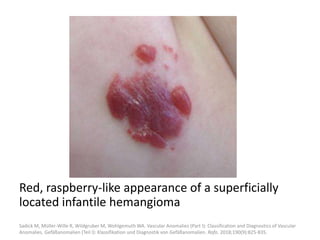

2) Infantile hemangiomas are the most common vascular tumor of infancy, affecting around 2-3% of children, most commonly on the face and neck.

3) They typically appear as red, raised lesions within the first few months of life and then slowly involute over 5-10 years, leaving residual discoloration or texture changes to the skin.

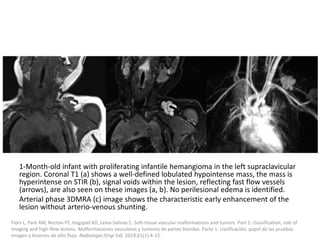

![b) MRI: Differ according to the biologic phase.

Proliferating phase:

they present as well-defined masses, hypointense

on T1 and hyperintense on T2, often with

presence of internal flow voids on spin-echo (SE)

imaging reflecting high-flow vessels.

High-flow vessels appear hyperintense on GRE

permitting the distinction with phlebolitis or

other calcifications, which are hypointense on all

imaging sequences.

. Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged IM, Norton PT, Matsumoto AH, Angle JF, et al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations:

diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics. 2011;31:321---40 [discussion 1340-1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-35-320.jpg)

![Medical treatment is usually attempted first,

with propranolol used as a first-line therapy

with excellent results.

it reduces the expression of VEGF and other

proangiogenic factors while also inducing

apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells;

excellent results have been reported.

Léauté-Labrèze C, Taïeb A. Efficacy of betablockers in infantile capillary haemangiomas: the physiopathological significance and

therapeutic consequences [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2008;135(12):860–862.

Dubois J, Alison M. Vascular anomalies: what a radiologist needs to know. Pediatr Radiol 2010;40(6): 895–905.

Mulligan PR, Prajapati HJ, Martin LG, Patel TH. Vascular anomalies: classification, imaging characteristics and implications for

interventional radiology treatment approaches. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130392.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-43-320.jpg)

![b) MRI:

Present as lobulated, non-mass like lesions with

low to intermediate signal intensity on T1 and

hyperintensity on T2 and STIR.

Occasionally, hemorrhage or high protein

content may cause internal fluid-fluid levels.

In cases of thrombosis or hemorrhage,

heterogeneous signal intensity can be

observed on T1.

Ernemann U, Kramer U, Miller S, et al. Current concepts in the classification, diagnosis and treatment of vascular anomalies. Eur J

Radiol 2010;75 (1):2–11.

Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged IM, Norton PT, Matsumoto AH, Angle JF, et al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations:

diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics. 2011;31:1321-40 [discussion 1340-1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-79-320.jpg)

![VMs may infiltrate multiple tissue planes and fat

suppressed T2 and STIR provide excellent

delineation of the extension of the lesions.

Contrast administration is helpful and often

shows slow, gradual, delayed heterogeneous

contrast filling with characteristic diffuse

enhancement of the slow flowing venous

channels on delayed post-contrast T1.

Dubois J, Alison M. Vascular anomalies: what a radiologist needs to know. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:895-905.

Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged IM, Norton PT, Matsumoto AH, Angle JF, et al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations:

diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics. 2011;31:1321---40 [discussion 1340-1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-81-320.jpg)

![Treatment

Conservative management

Sclerotherapy

Endovenous ablation techniques

Post-procedural care

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-88-320.jpg)

![Polidocanol foam

Preparation of

Aethoxysklerol foam.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-97-320.jpg)

![Venous malformation

(a) STIR sequence showed

a hyperintense venous

malformation with central

phleboliths (arrow)

(b) Percutaneous

puncture of the venous

malformation.

(c) Injection of contrast

media into the venous

malformation

(d) Injection of Polidocanol

foam.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-102-320.jpg)

![Classification of venous

malformations

Type I lesions are

isolated

malformations

without

phlebographically

visible venous

drainage.

Type II lesions

demonstrate normal-

sized venous drainage.

Type III lesions

demonstrate enlarged

venous drainage.

Type IV lesions are

composed of

essentially ectatic

dysplastic veins.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-104-320.jpg)

![Additionally, local compression of visible

draining veins may be considered.

In some cases it is necessary to puncture the VM

more than once to treat the lesion completely.

However, injection has to be stopped if there is

increased resistance, extravasation of the

sclerosant, or skin blanching.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-106-320.jpg)

![Post-procedural care

Patients should wear their compression garments

to help involution of the lesion.

Limb elevation, ice packs, and pain medication (an

NSAID is normally sufficient) may be indicated.

To prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT),

prophylactic anticoagulation with LMWH is

recommended.

Ultrasound should be performed to exclude DVT

one day after therapy of limb VMs.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-109-320.jpg)

![Applications techniques

Cysts are cannulated with a needle under real-time

ultrasound guidance.

Alternatively, a pigtail catheter (3 to 5 French) can

be inserted in larger cysts, as the multiple side

holes facilitate aspiration of the lymphatic fluid

before injection of the sclerosing agent.

Contrast media can be injected to visualize the

whole lesion under fluoroscopy.

After aspiration of the entire cyst content, the LM

can then be treated with the sclerosant.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-142-320.jpg)

![Clinical presentation

Unlike VMs, CMs are usually present as a

macular pink to dark red patch with irregular

borders without bruit or local warmth.

Like LMs, they are usually localized in the head

and neck region.

Symptoms may be the result of deeper

associated malformations.

Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:412-22.

Berenguer B, Burrows PE, Zurakowski D, Mulliken JB. Sclerotherapy of craniofacial venous malformations: complications and results. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1999;104:1-11 [discussion 12-5].

Fayad LM, Hazirolan T, Bluemke D, Mitchell S. Vascular malformations in the extremities: emphasis on MR imaging features that guide treatment options.

Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35: 127-37.

Ernemann U, Kramer U, Miller S, Bisdas S, Rebmann H, Breuninger H, et al. Current concepts in the classification, diagnosis and treatment of vascular

anomalies. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:2-11.

Behr GG, Johnson CM. Vascular anomalies: hemangiomas and beyond -part 2, slow-flow lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:423-36.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-147-320.jpg)

![The goal of endovascular embolotherapy is to

occlude the nidus or fistula completely.

Commonly used agents are:

Ethanol

N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA)

Ethylene-vinyl-alcohol-copolymer (EVOH)

Coils and plugs

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-208-320.jpg)

![Because of its low viscosity, ethanol passes the

nidus very quickly into the lung circulation.

Therefore, the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP)

should be monitored continuously during ethanol

application.

PAP above 25mmHg systolic can be found 10 to 15

minutes after application.

To avoid side effects, it is preferred to administer

less than 0.5 ml per kg bodyweight in small

aliquots.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-210-320.jpg)

![As the liquid agent strictly follows the blood

flow, it is rarely possible to occlude the

complete nidus in large peripheral AVMs.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-212-320.jpg)

![Ethylene-vinyl-alcohol-copolymer (EVOH), EVOH is a non-adhesive liquid

embolic agent mixed with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and radiopaque

tantalum powder.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-215-320.jpg)

![EVOH (*) can be administered in a controlled manner under fluoroscopy, the

distribution of EVOH can be followed easily using the “road map” technique

(arrow).

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-216-320.jpg)

![Plug and push

technique.

Using the reflux of

EVOH as a plug around

the detachable tip of

the microcatheter, an

active forward flow of

EVOH into the whole

nidus is possible

regardless of the flow

direction.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-217-320.jpg)

![Plugs and coils

Coils or vascular plugs are needed in some cases to

optimize hemodynamics for further treatment,

but those only occlude the feeding vessels and

never reach the actual nidus, therefore, their use

is considered as adjuvant, and mere coiling of

AMVs is obsolete nowadays.

Plugs and coils can be used in simple structured

AVMs (type 1), for example in pulmonary fast-flow

malformations, they also have a role as an embolic

agent for outflow occlusion (type II lesions).

Wohlgemuth WA, Muller-Wille R, Teusch VI et al. The retrograde transvenous push-through method: a novel treatment of peripheral

arteriovenous malformations with dominant venous outflow. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2015; 38: 623–63

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-218-320.jpg)

![Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-246-320.jpg)

![After embolization, long-term clinical

surveillance with intermittent imaging should

be performed to rule out recurrence.

Incomplete nidus embolization may stimulate

aggressive growth.

Müller-Wille R, Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Wohlgemuth WA. Vascular Anomalies (Part II): Interventional Therapy of Peripheral Vascular

Malformations [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Gefäßanomalien (Teil II): Interventionelle Therapie von peripheren

Gefäßmalformationen [published online ahead of print, 2018 Feb 7]. Rofo. 2018;10.1055/s-0044-101266.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vascularanomalies-220929223146-3387dd4d/85/Vascular-anomalies-pptx-248-320.jpg)