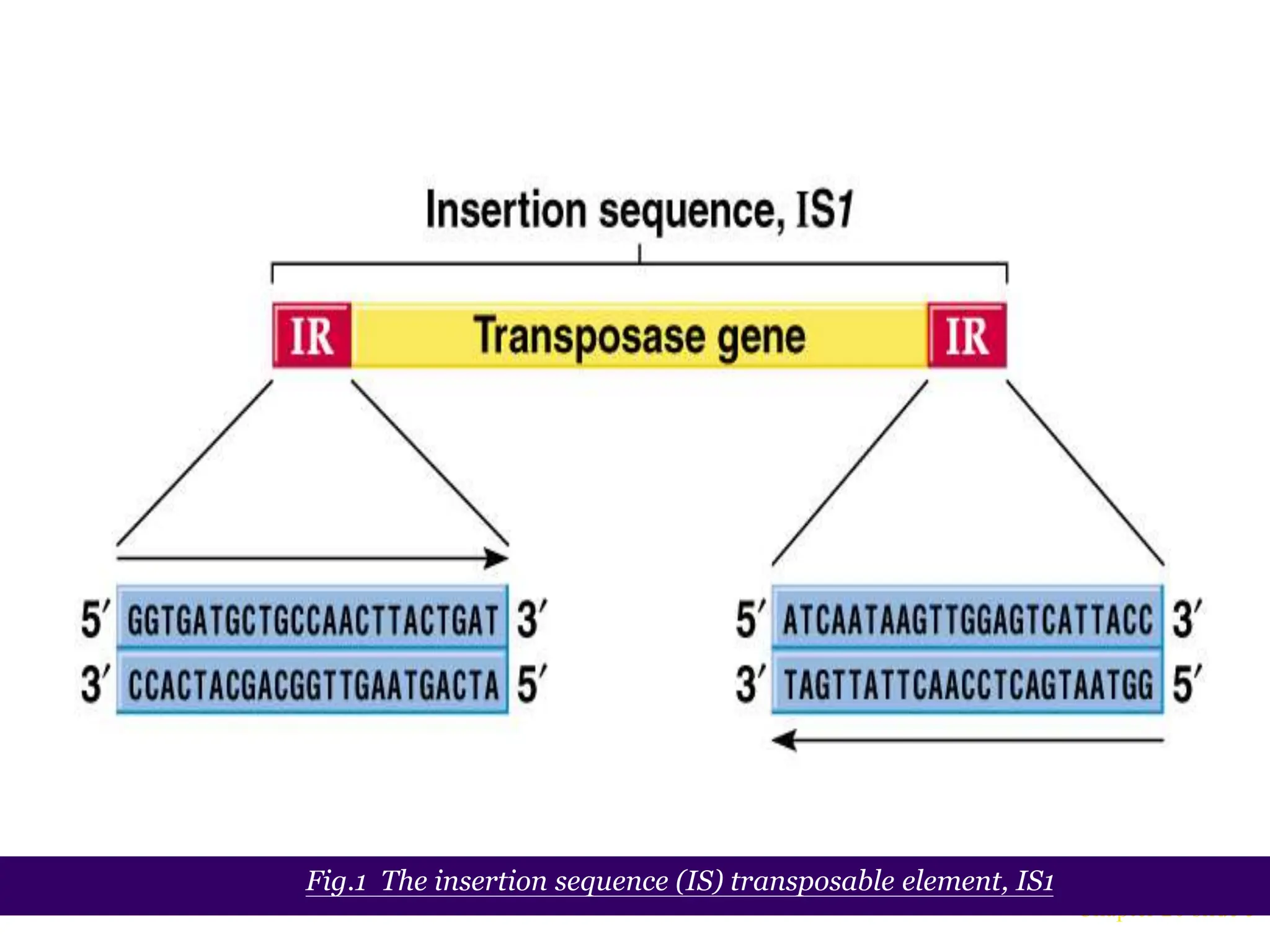

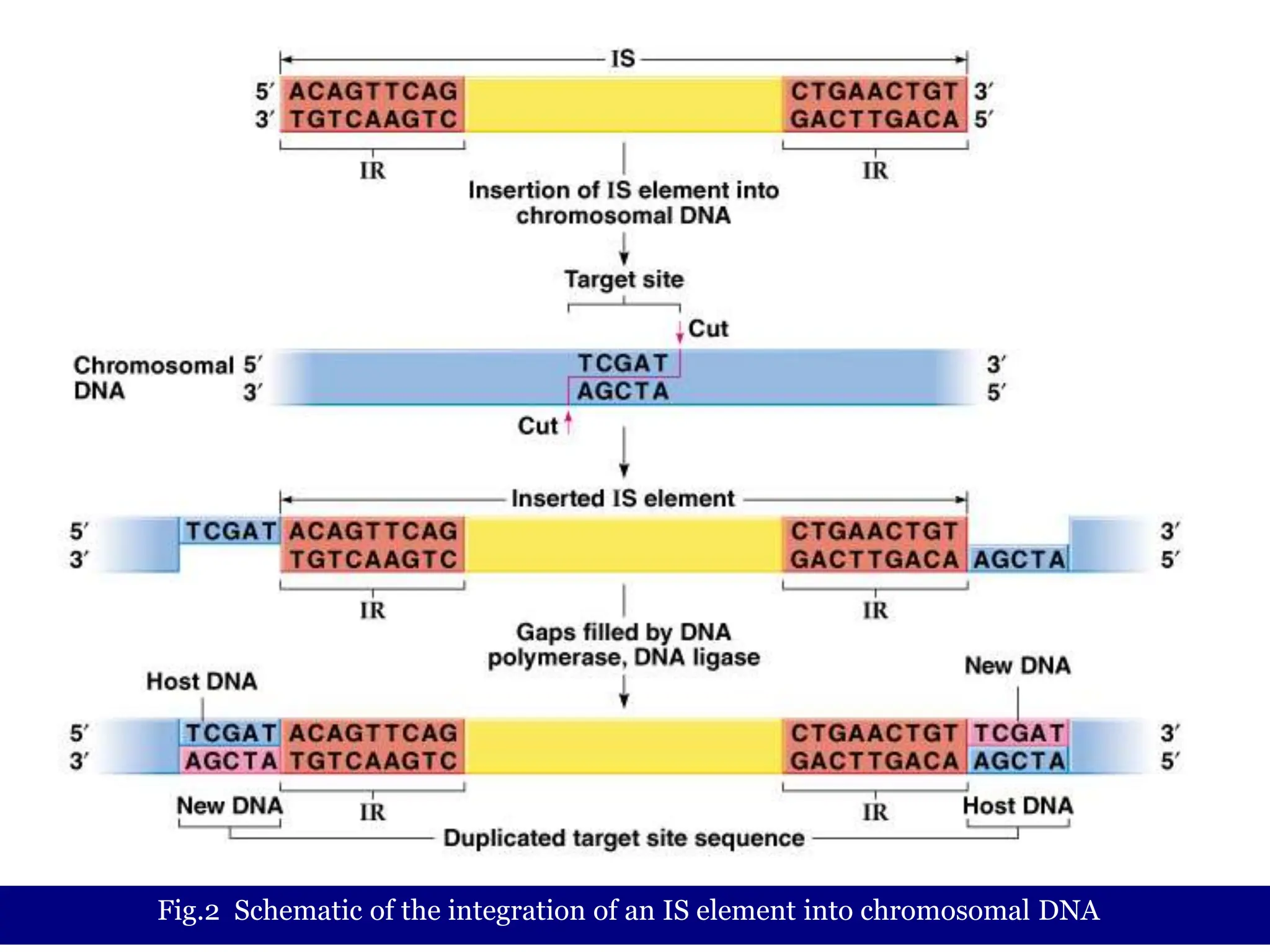

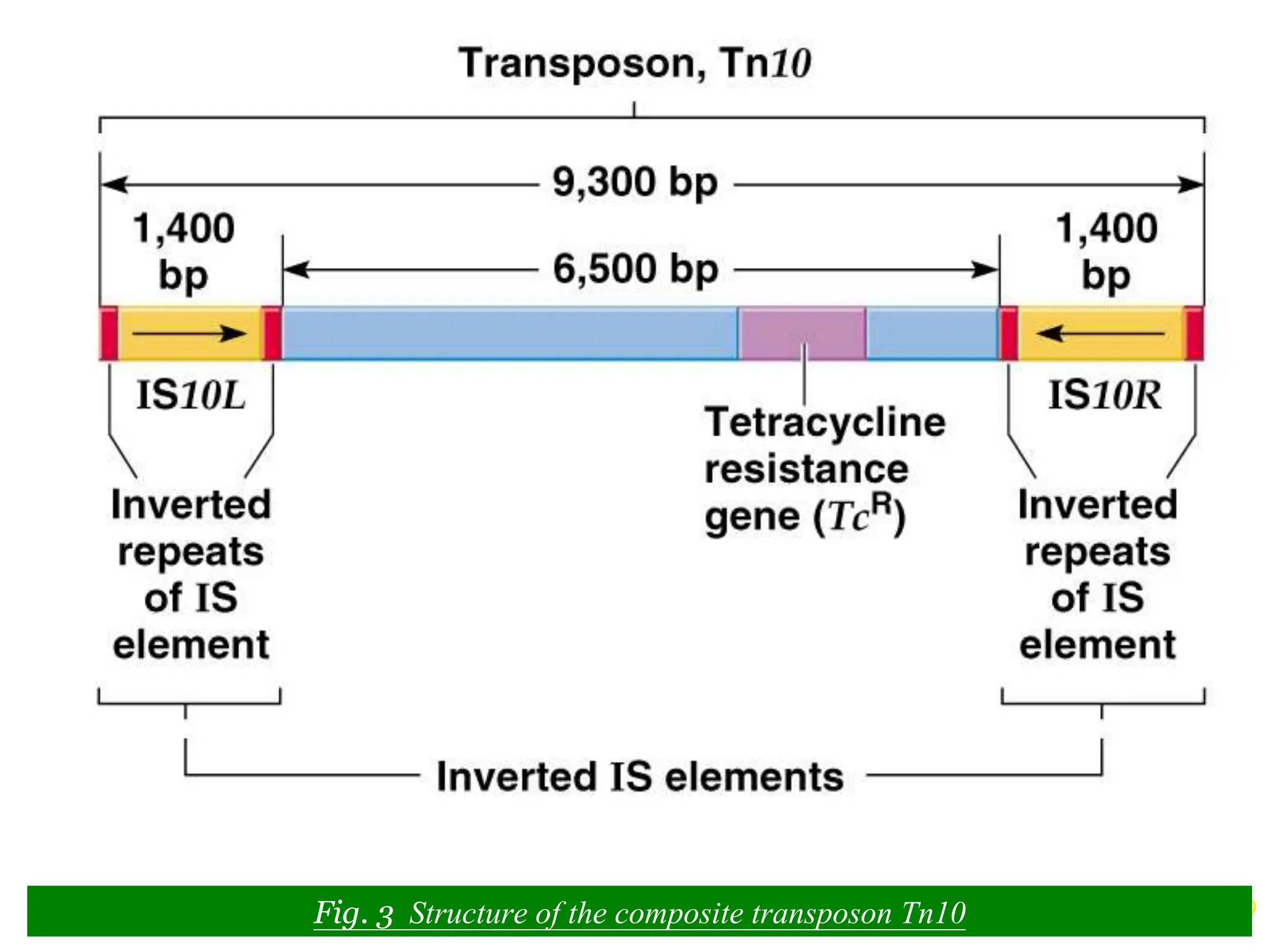

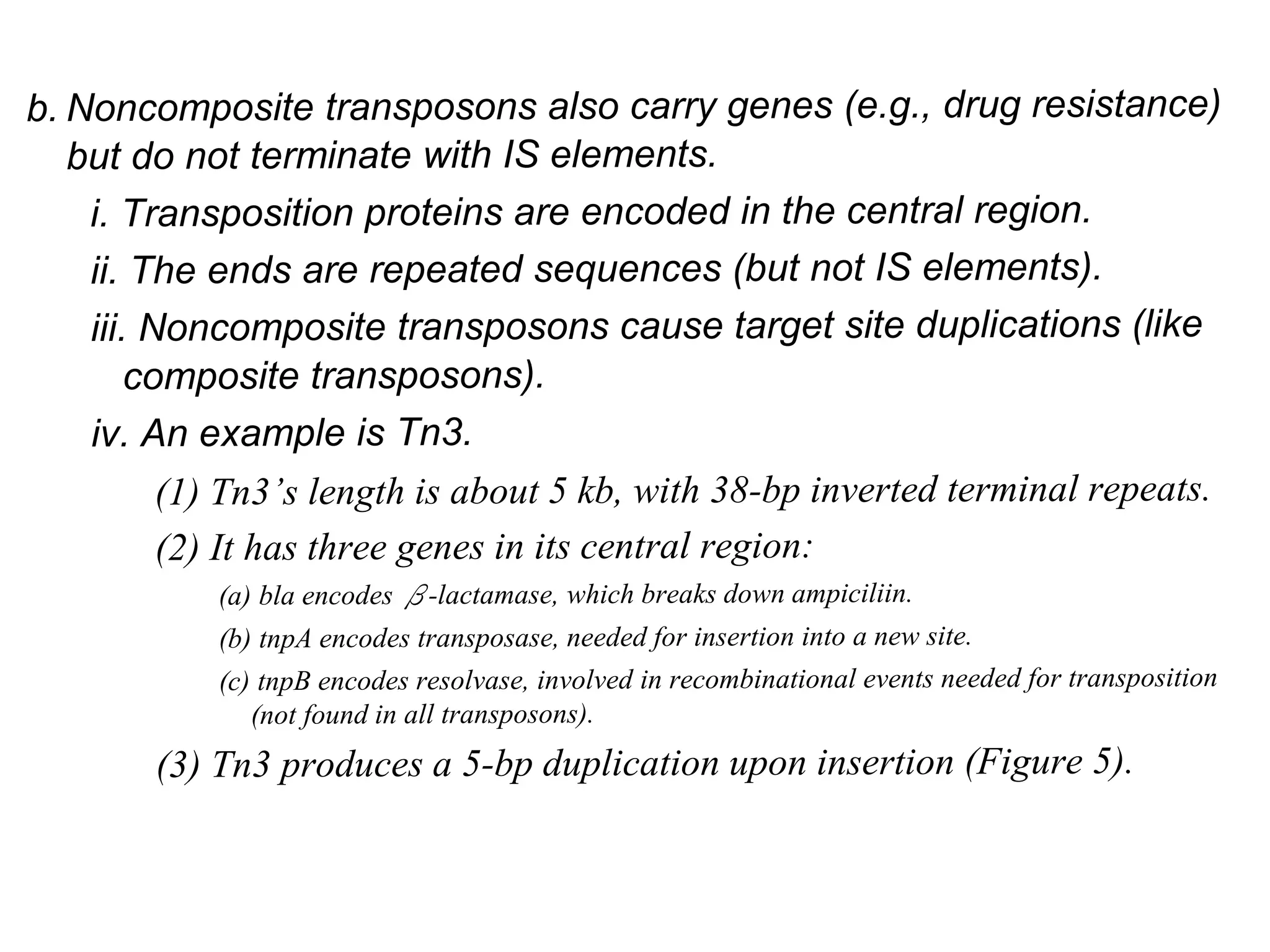

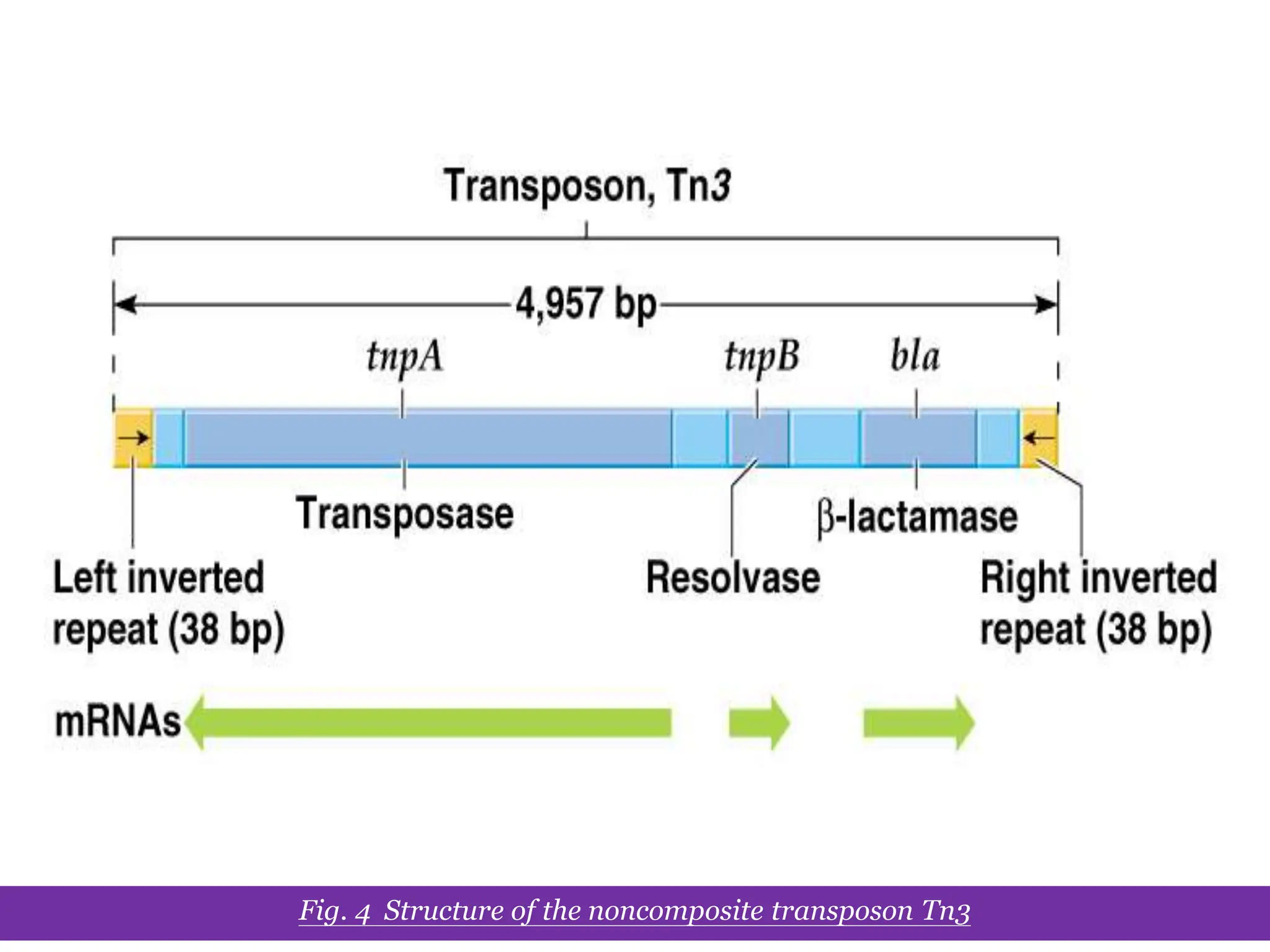

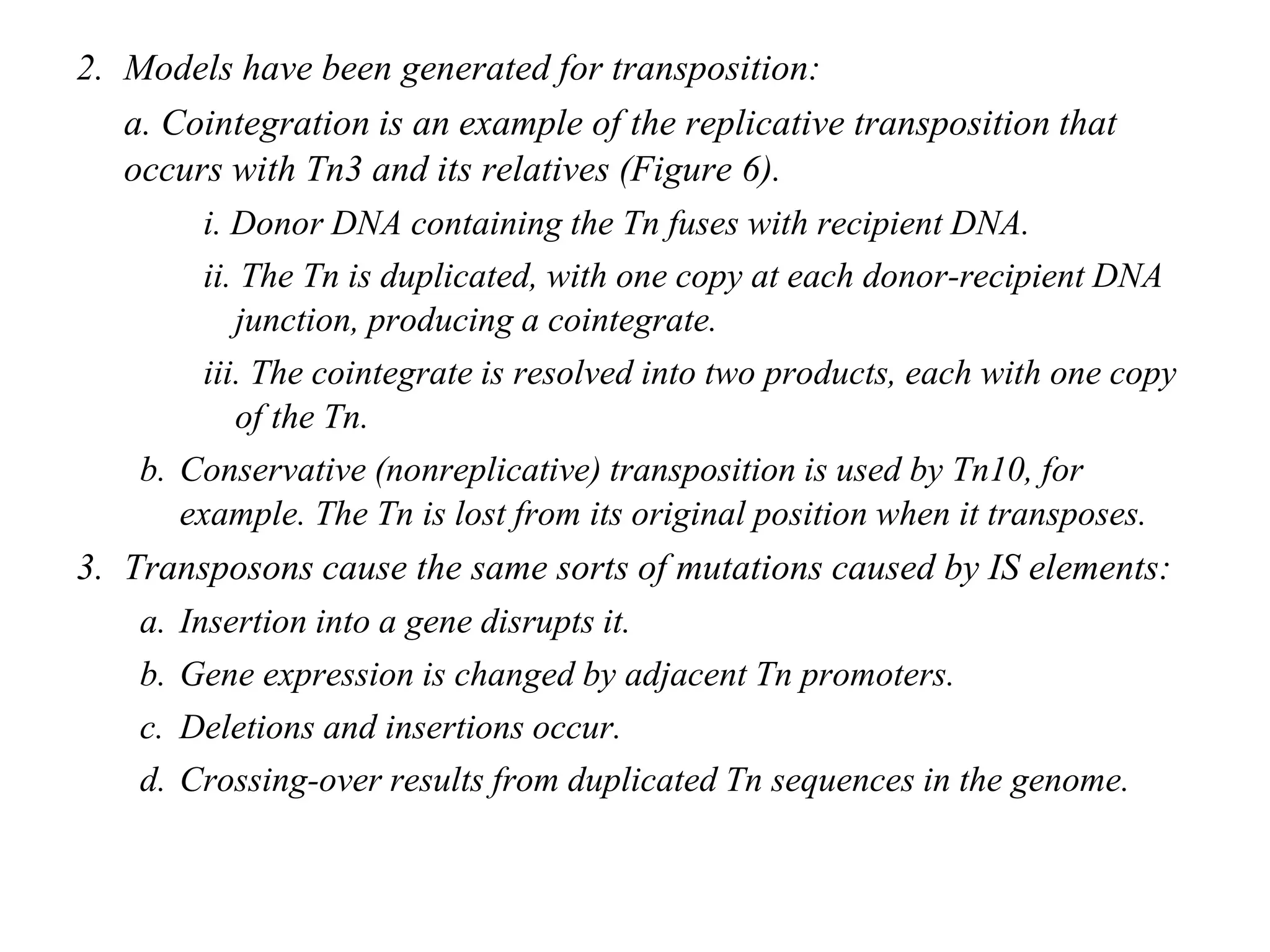

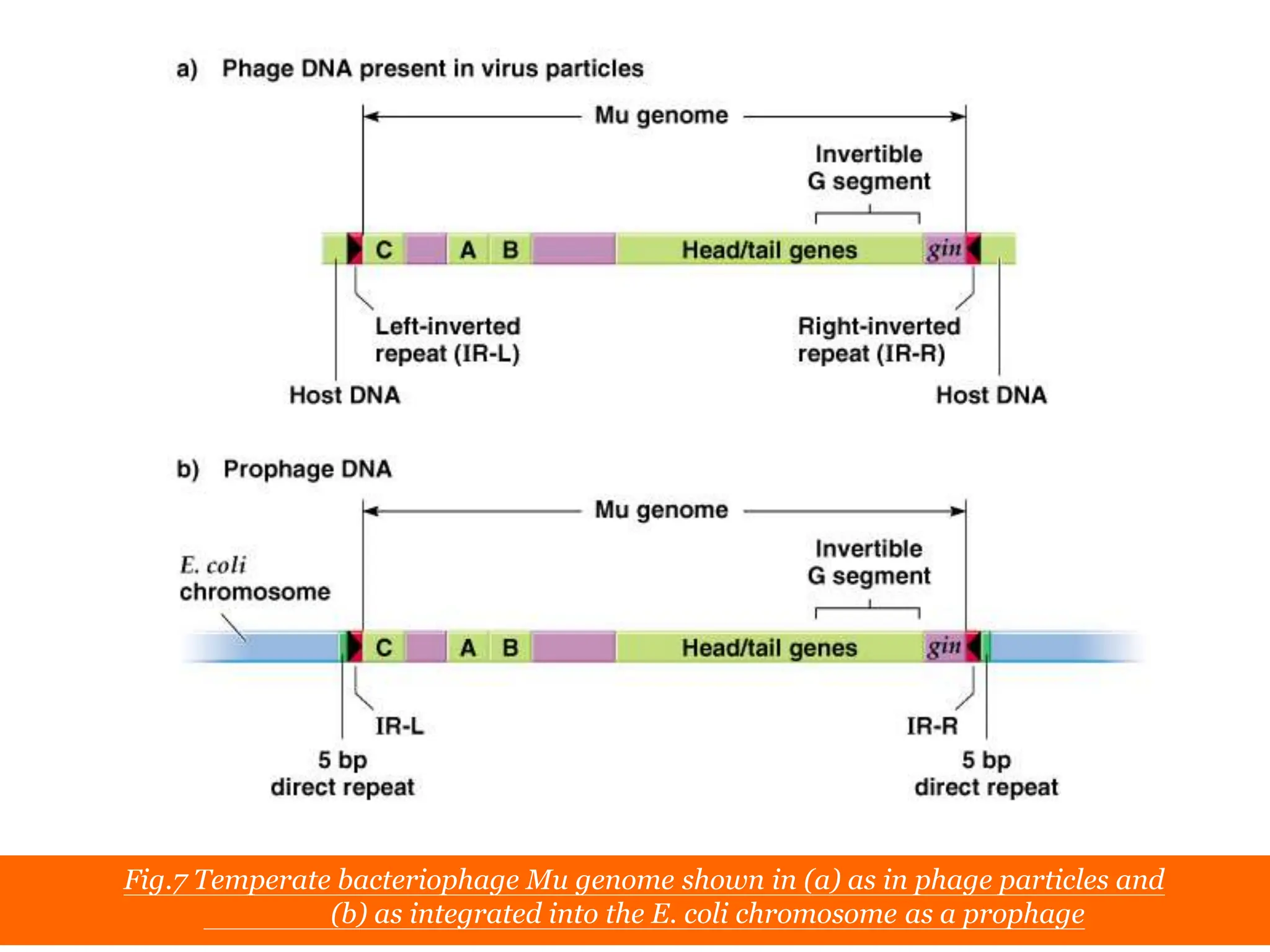

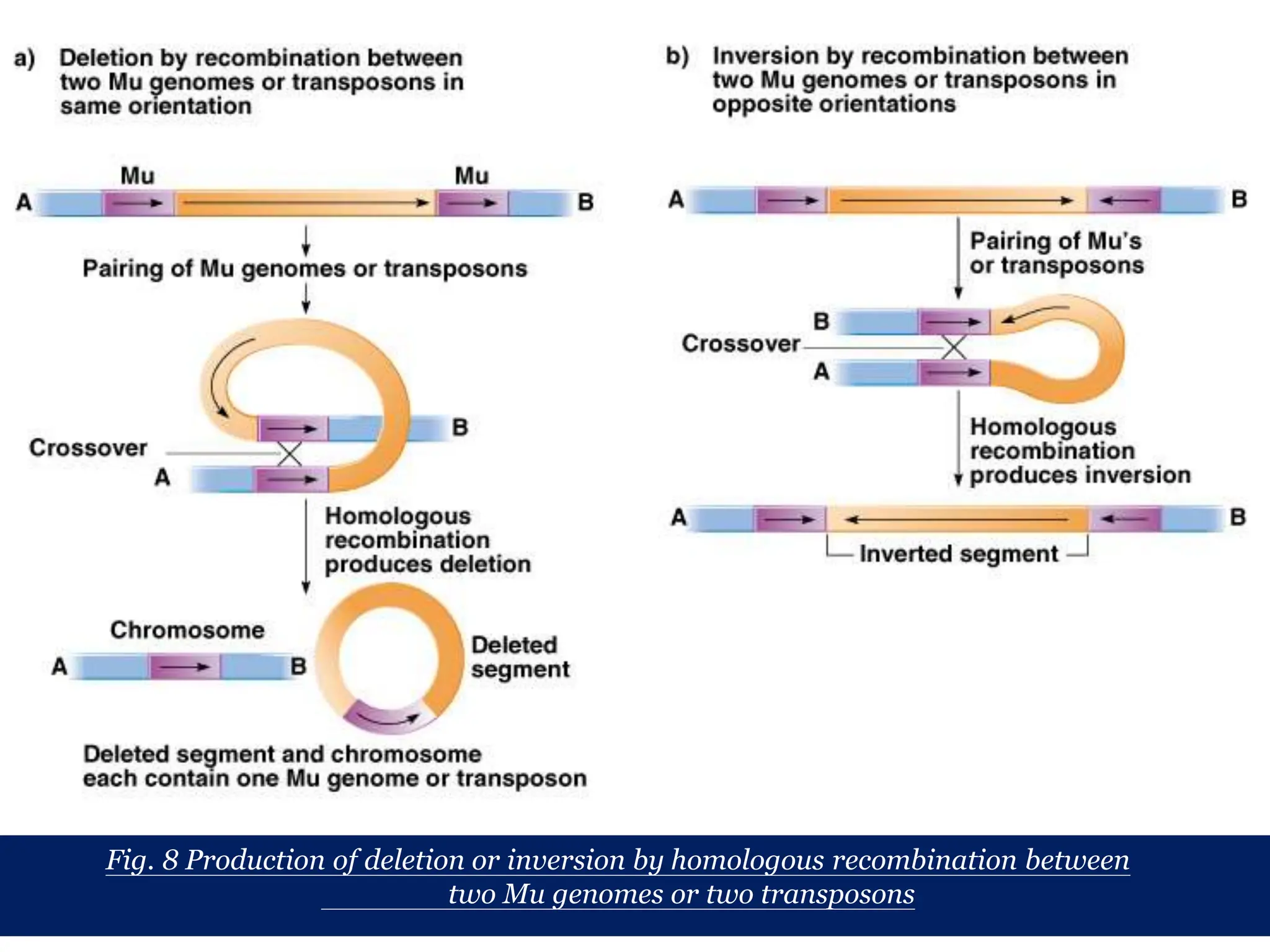

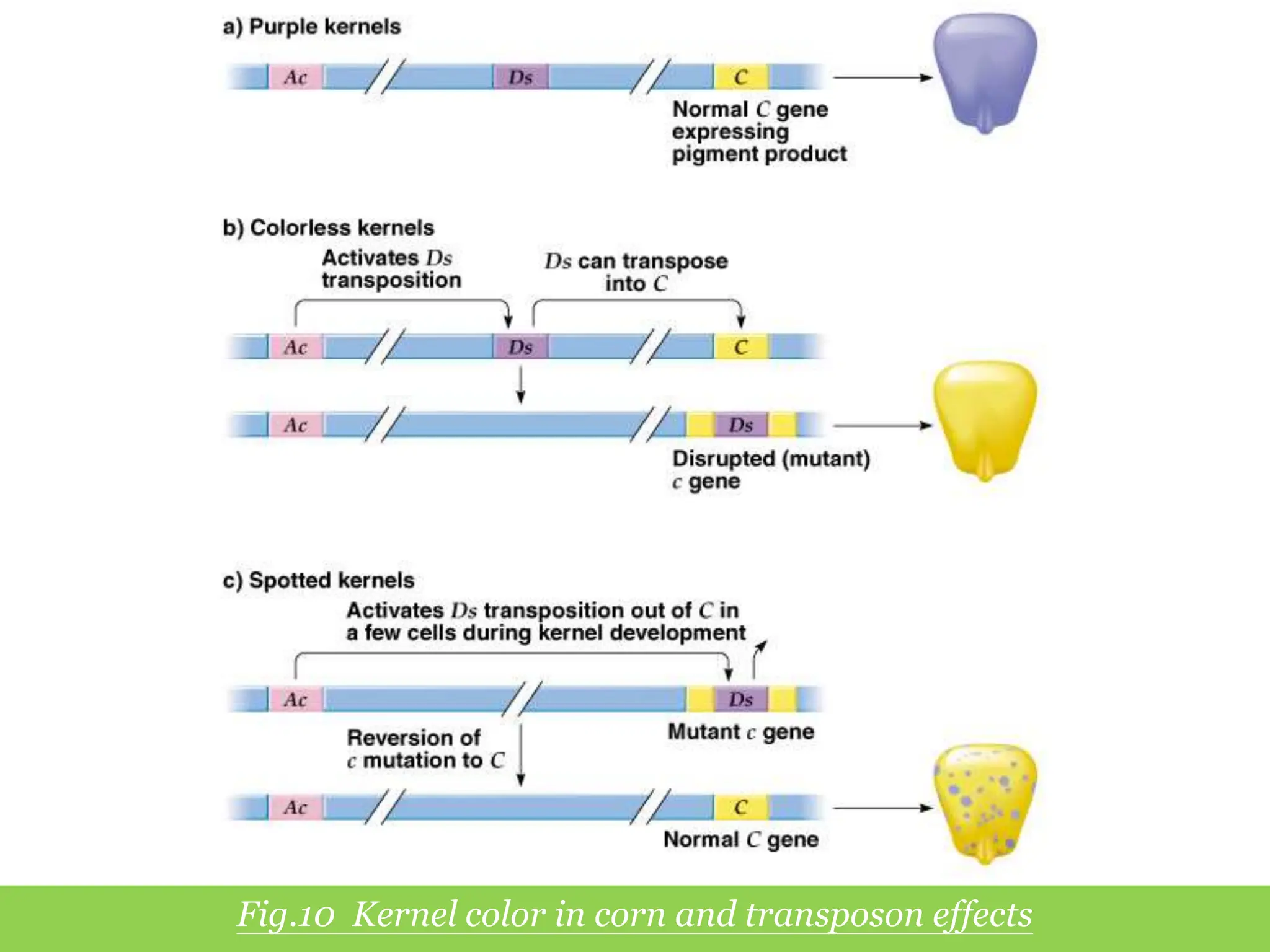

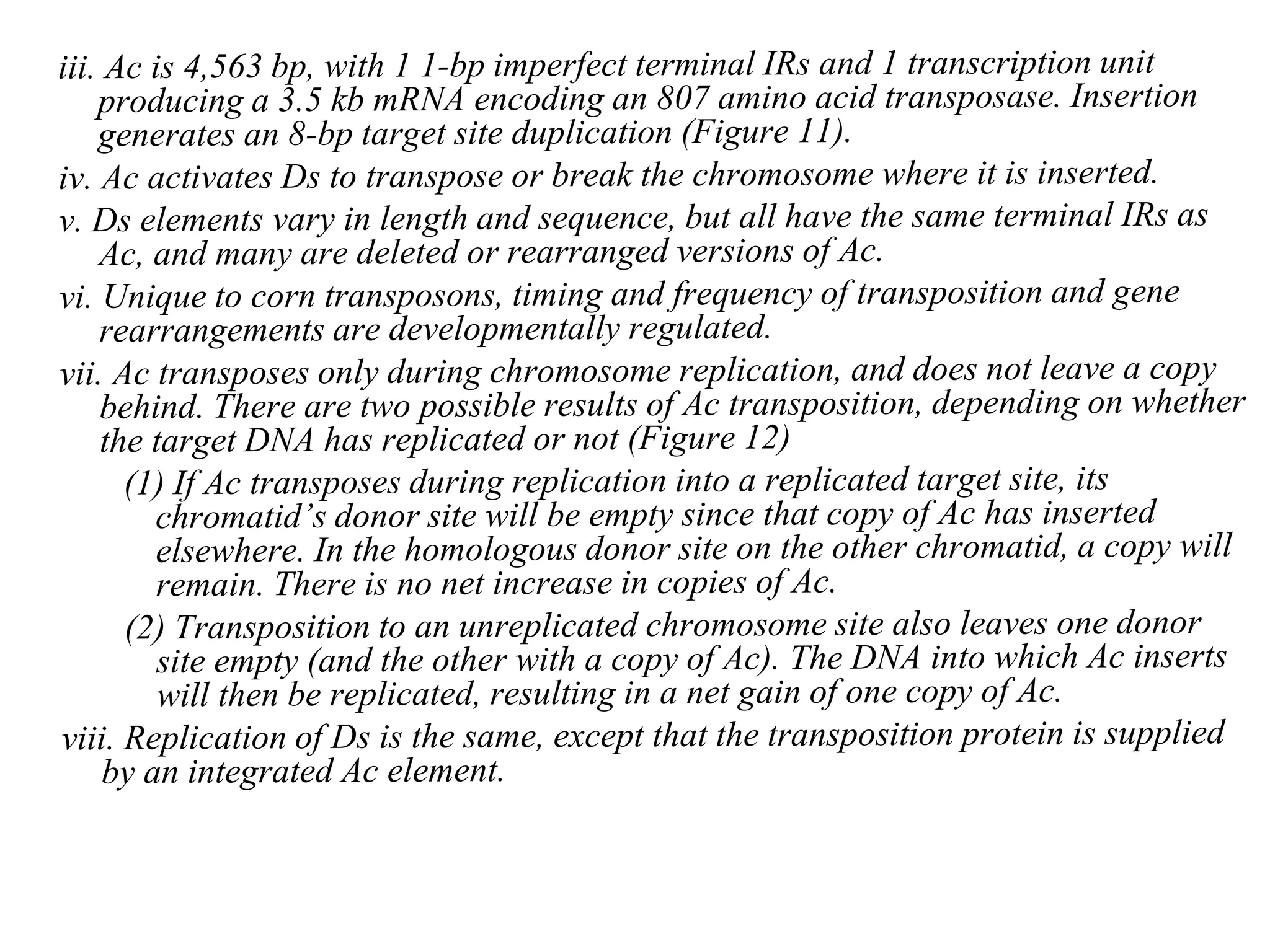

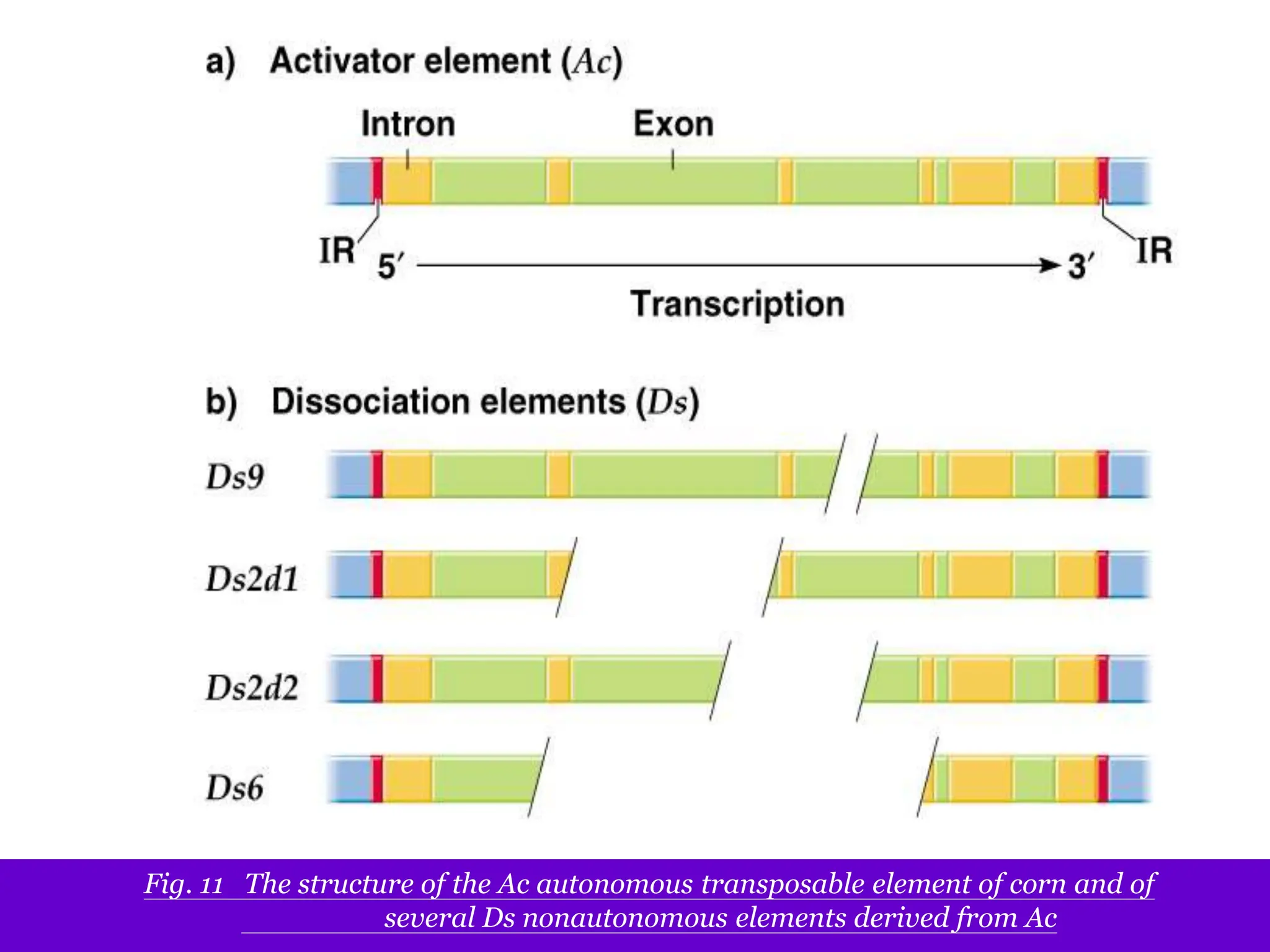

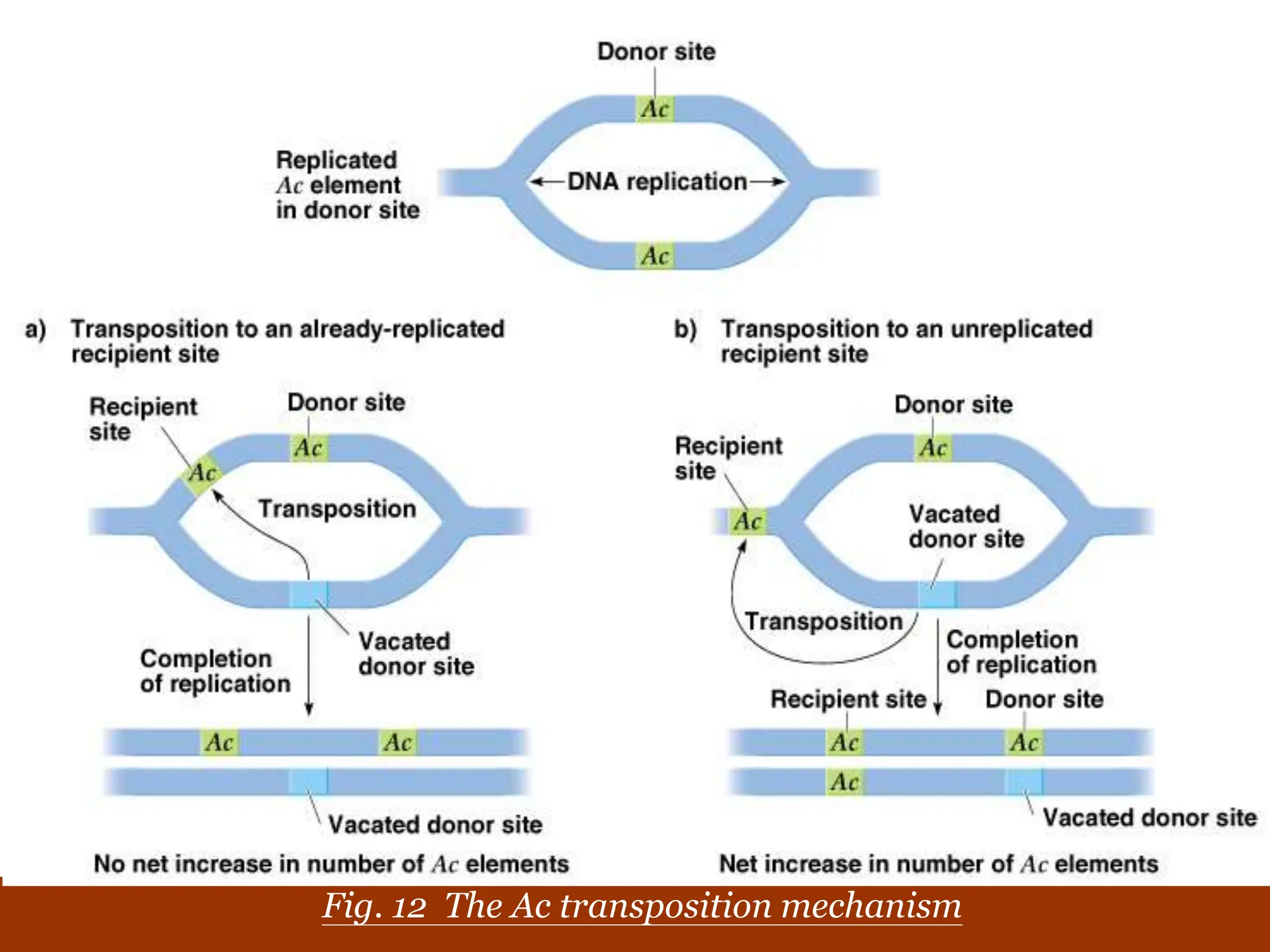

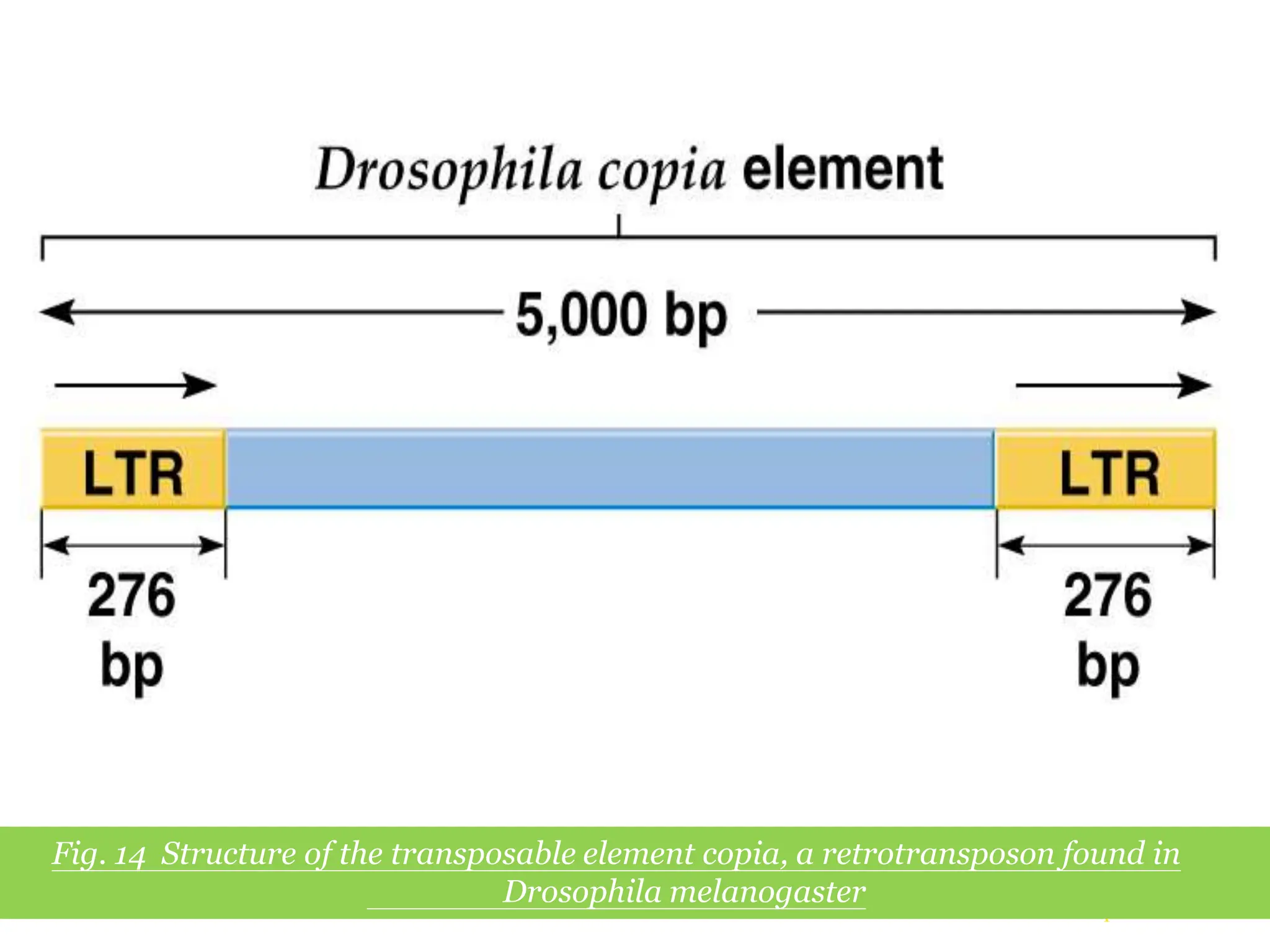

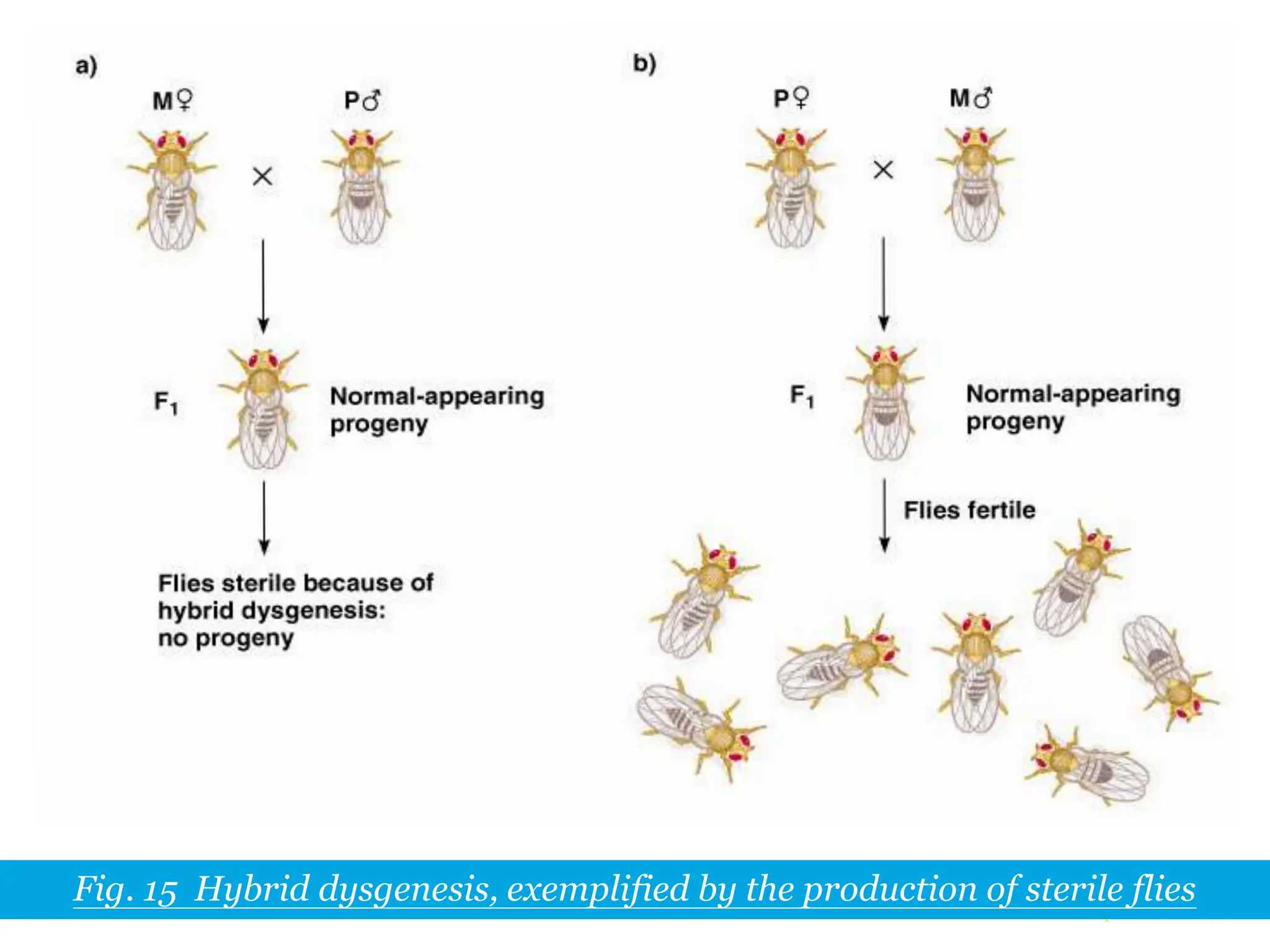

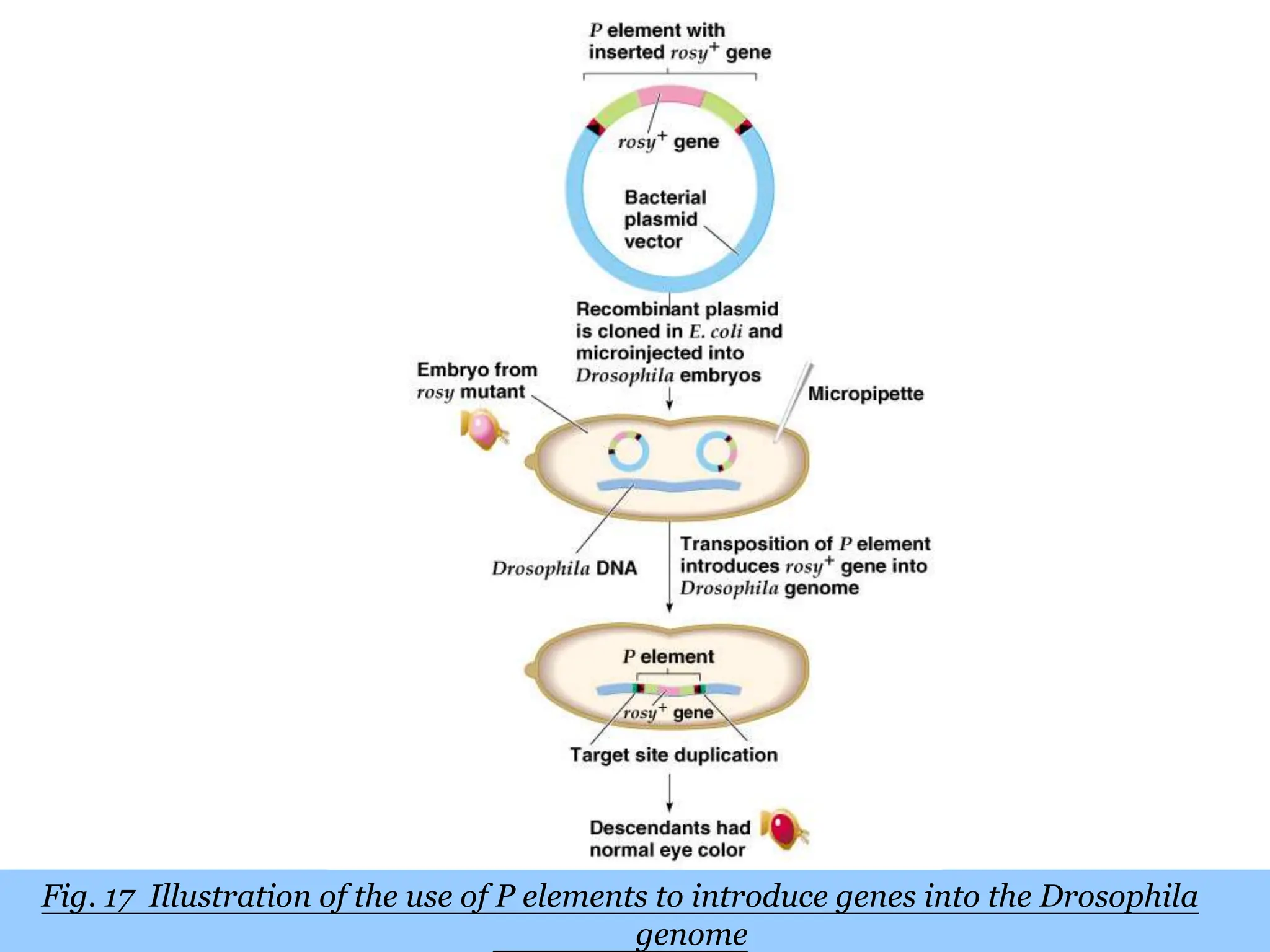

This document summarizes transposable elements and transposon mutagenesis. It discusses the general features of transposable elements, including their mechanisms of movement and ability to cause genetic changes. It then describes various types of transposable elements found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, examples discussed include insertion sequences, transposons like Tn10, and bacteriophage Mu. In eukaryotes, examples of plant transposons like Ac-Ds, yeast retrotransposons like Ty, and Drosophila transposons like copia and P elements are summarized. The structures, mechanisms of movement, and effects of insertion of several of these transposable elements