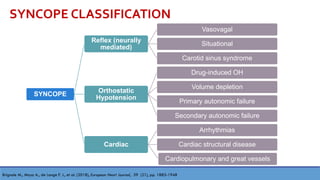

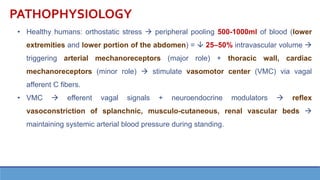

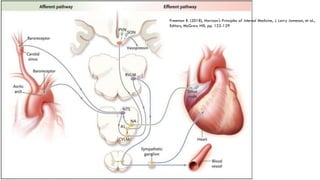

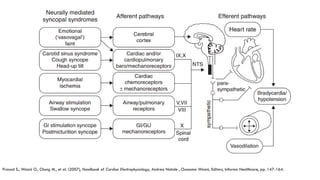

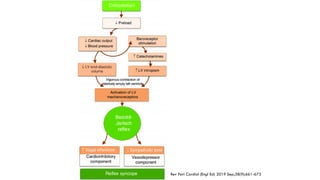

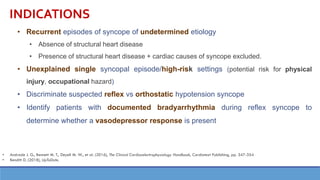

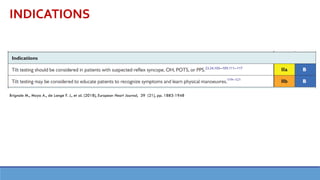

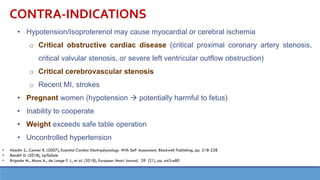

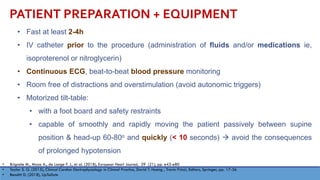

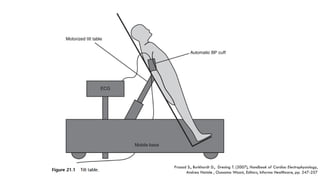

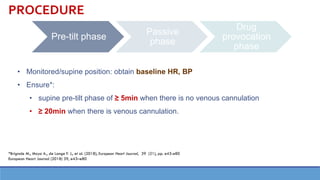

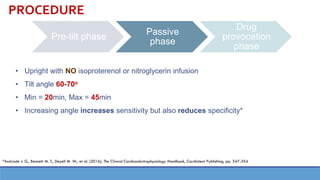

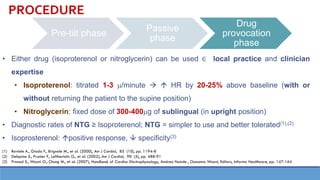

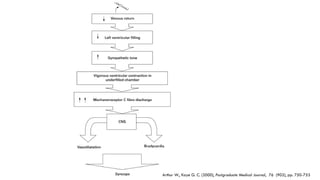

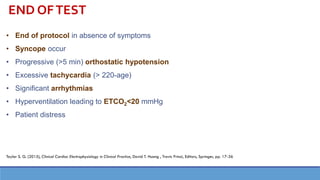

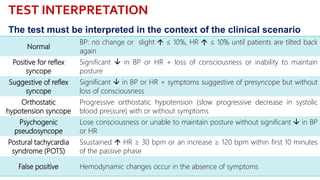

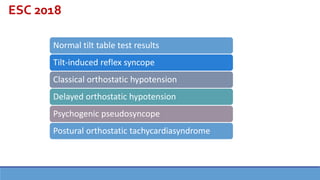

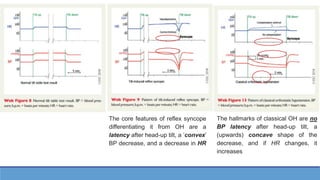

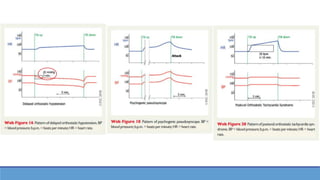

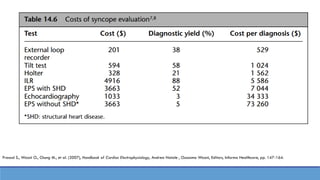

This document provides information about the tilt table test procedure for evaluating syncope of unknown cause. It describes the indications, contraindications, preparation, phases of the procedure including pre-tilt, passive, and drug provocation. Interpretation of normal and abnormal responses is outlined. Caveats are discussed that the test has limited specificity and sensitivity and a positive result may not reflect the mechanism of spontaneous syncope. Complications are typically minor. Overall, the tilt table test is a commonly used procedure to help classify syncope and determine if reflex vasovagal mechanisms are involved.