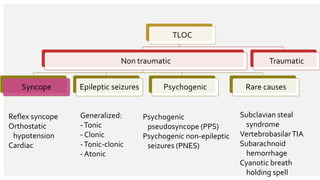

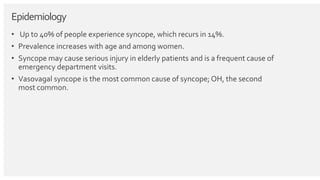

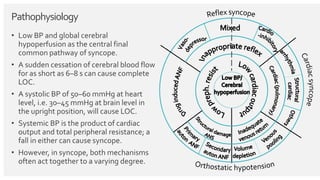

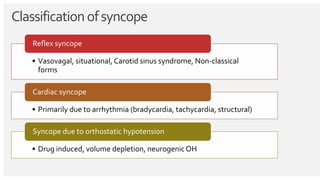

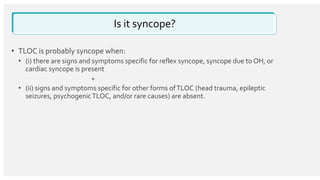

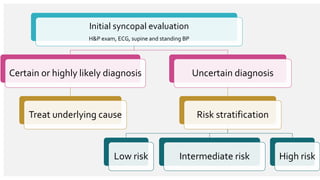

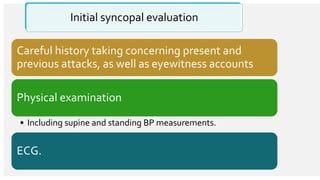

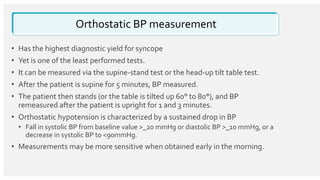

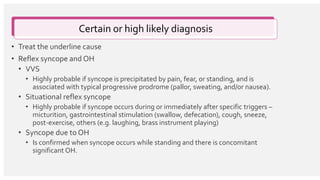

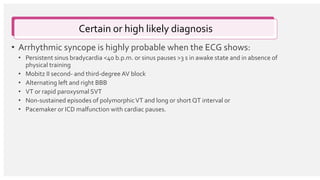

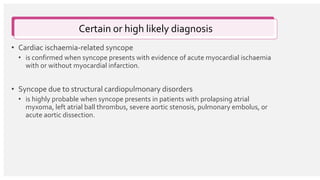

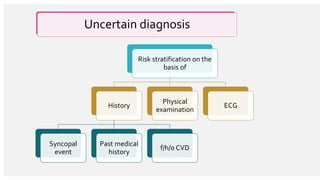

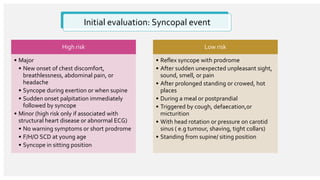

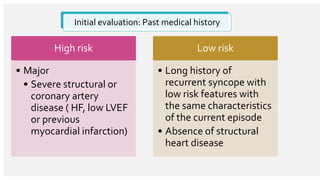

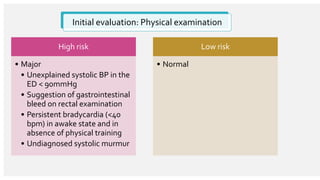

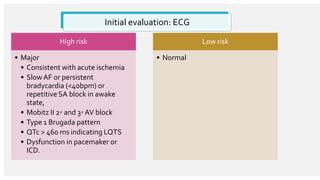

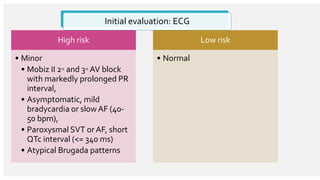

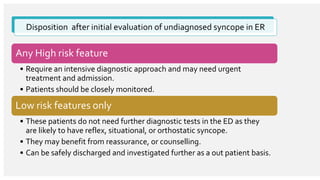

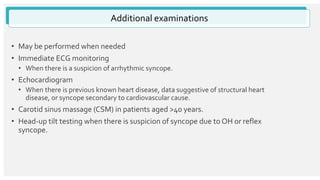

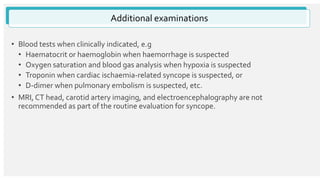

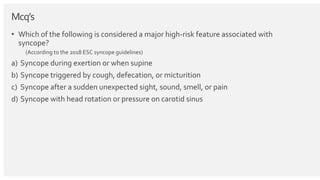

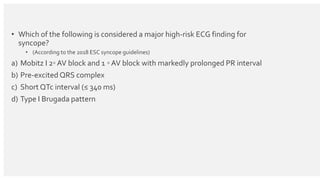

The document outlines the definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of syncope, which is characterized by brief loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion. It emphasizes the importance of initial patient evaluation in the emergency setting, including history taking, physical examination, and risk stratification, to identify high-risk features that may require intensive diagnostic approaches. Syncope management strategies are discussed, focusing on differentiating between various underlying causes such as reflex syncope, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac issues.

![Refrences

• Michele Brignole, Angel Moya, Frederik J de Lange, Jean-Claude Deharo, Perry

M Elliott, Alessandra Fanciulli, Artur Fedorowski, Raffaello Furlan, Rose Anne

Kenny, Alfonso Martín,Vincent Probst, Matthew J Reed, Ciara P Rice, Richard

Sutton, Andrea Ungar, J Gert van Dijk, ESC Scientific DocumentGroup; 2018

ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of

syncope, European Heart Journal,Volume 39, Issue 21, 1 June 2018, Pages

1883–1948, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy037

• emedicine.com. Accessed January 10, 2019].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/syncope-190112195920/85/Syncope-29-320.jpg)