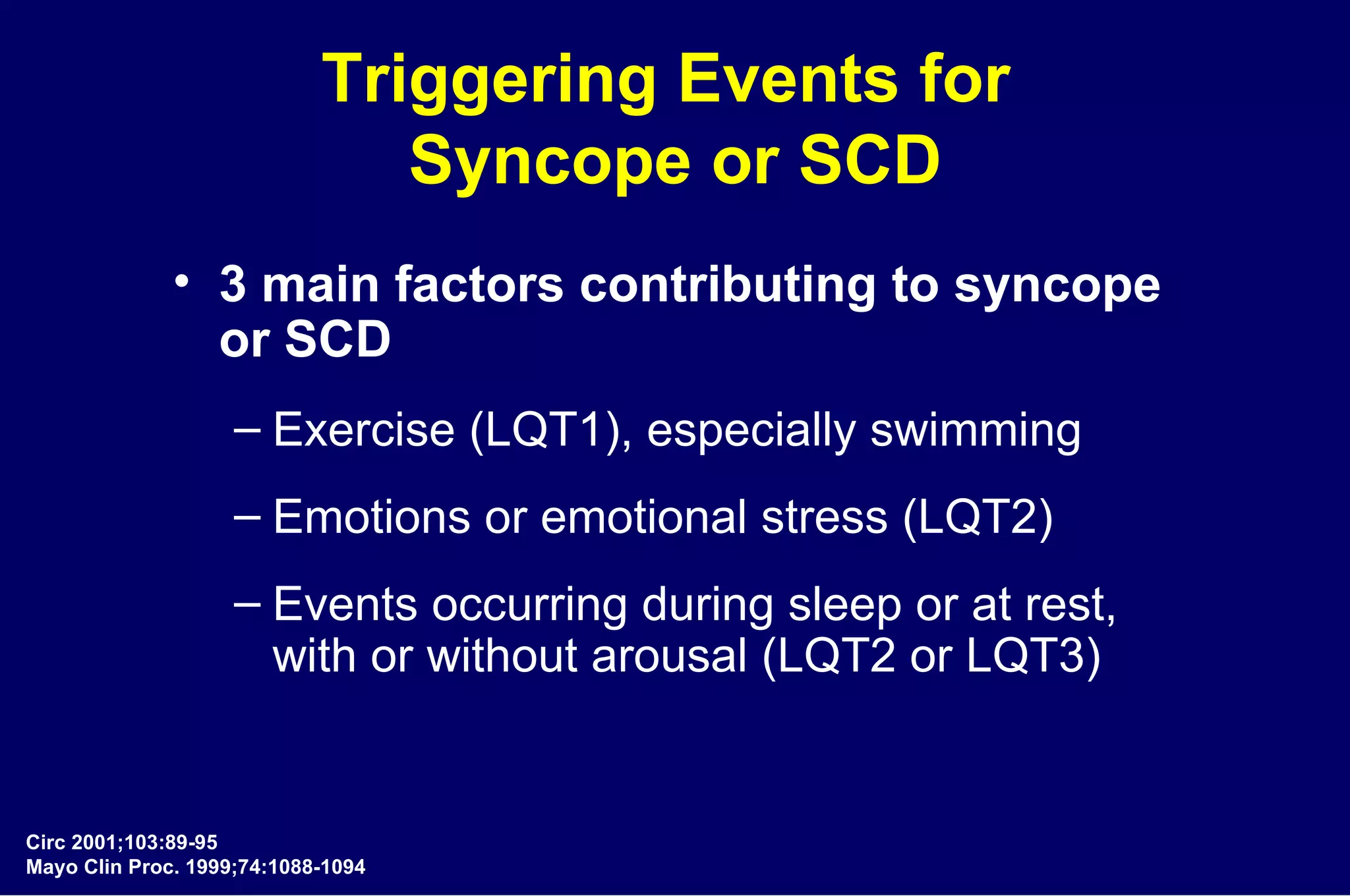

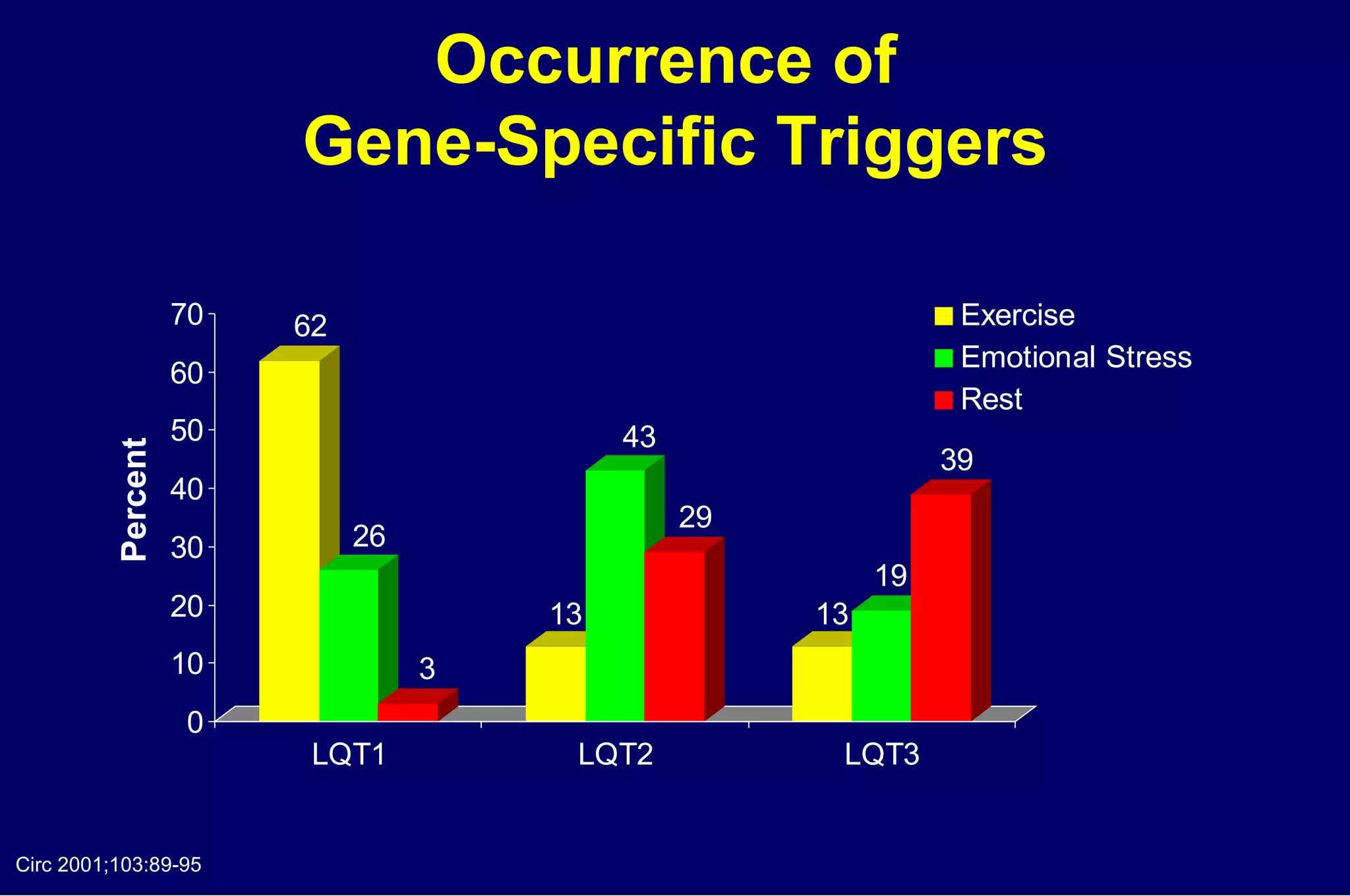

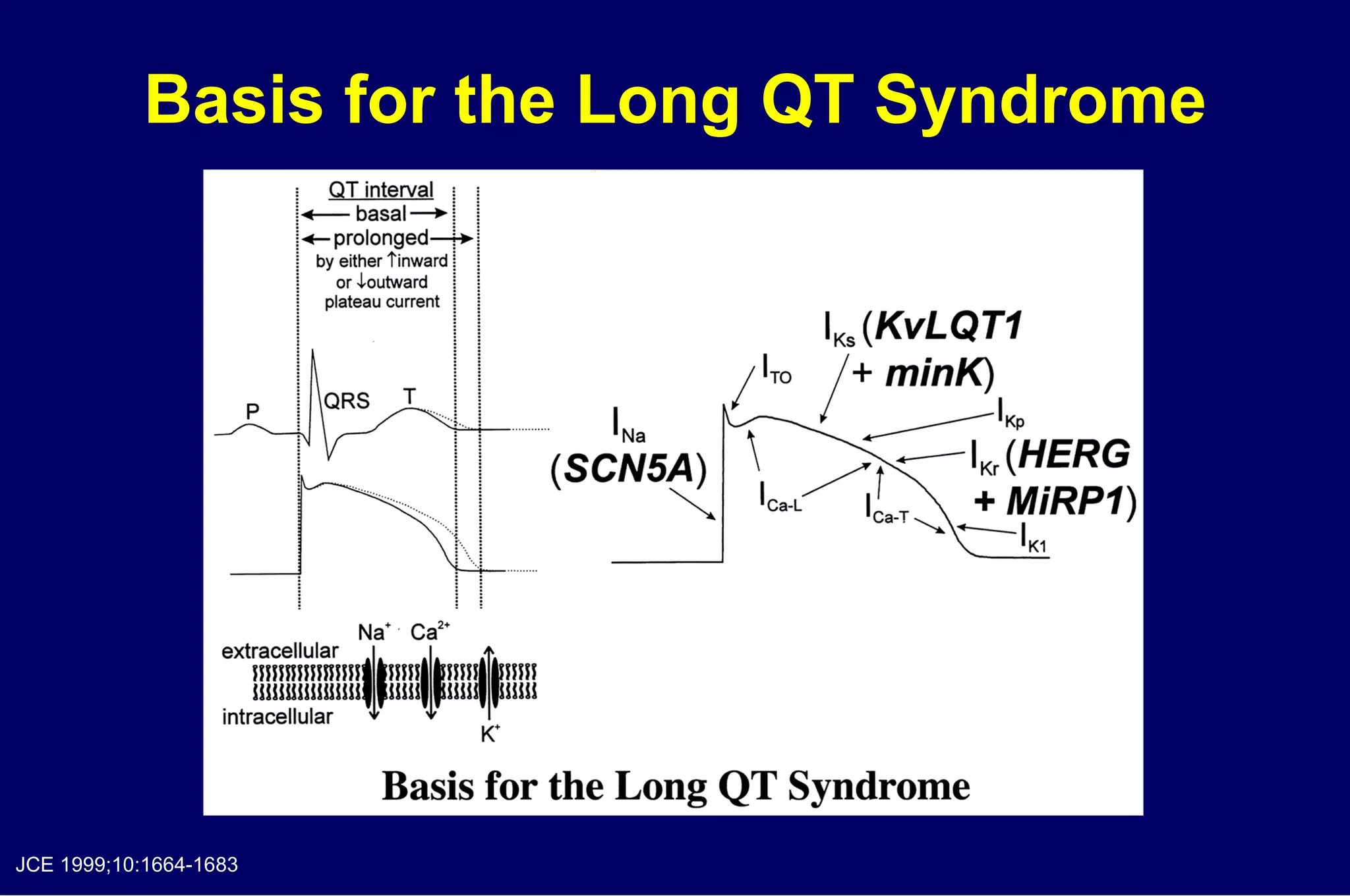

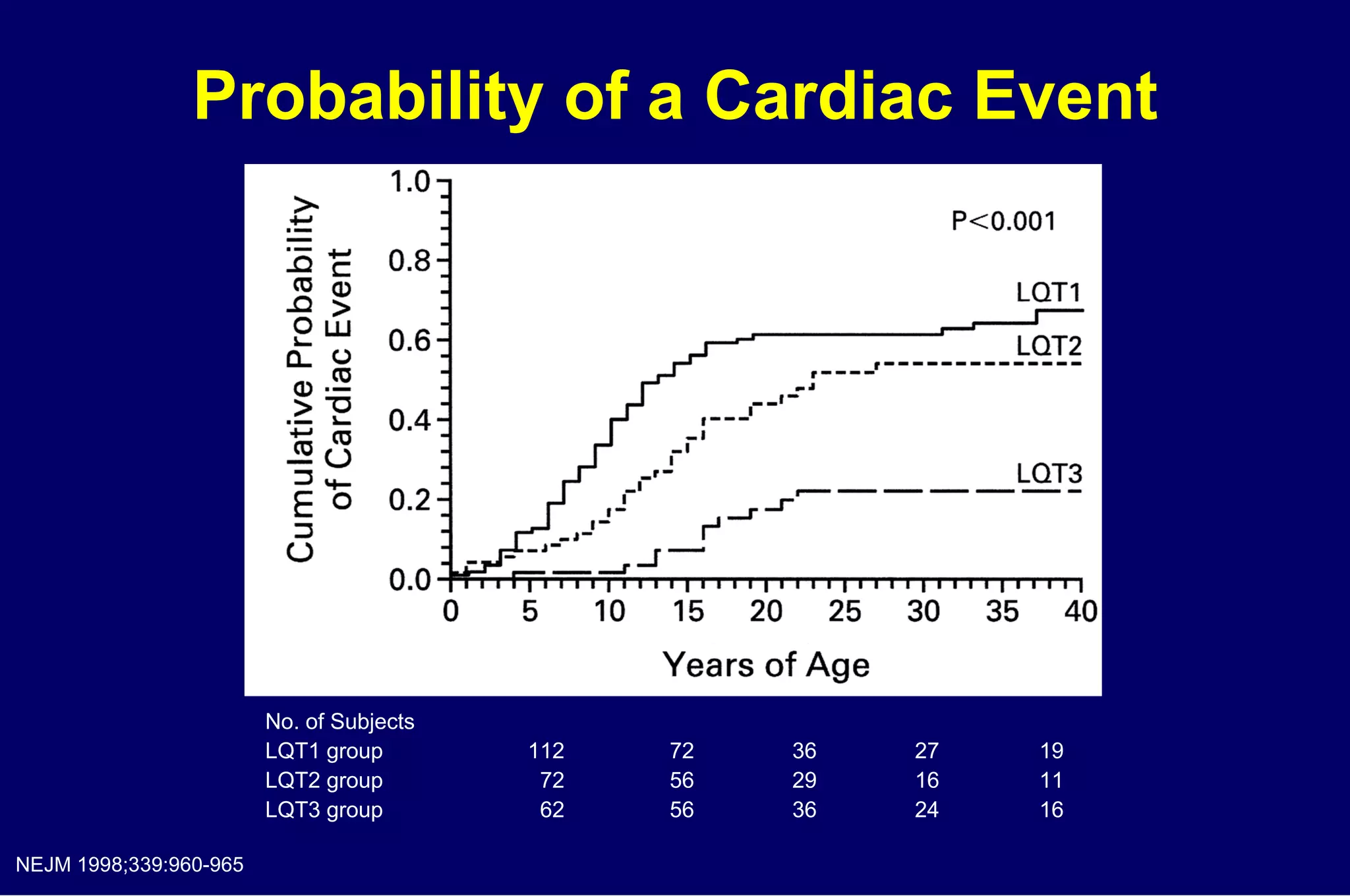

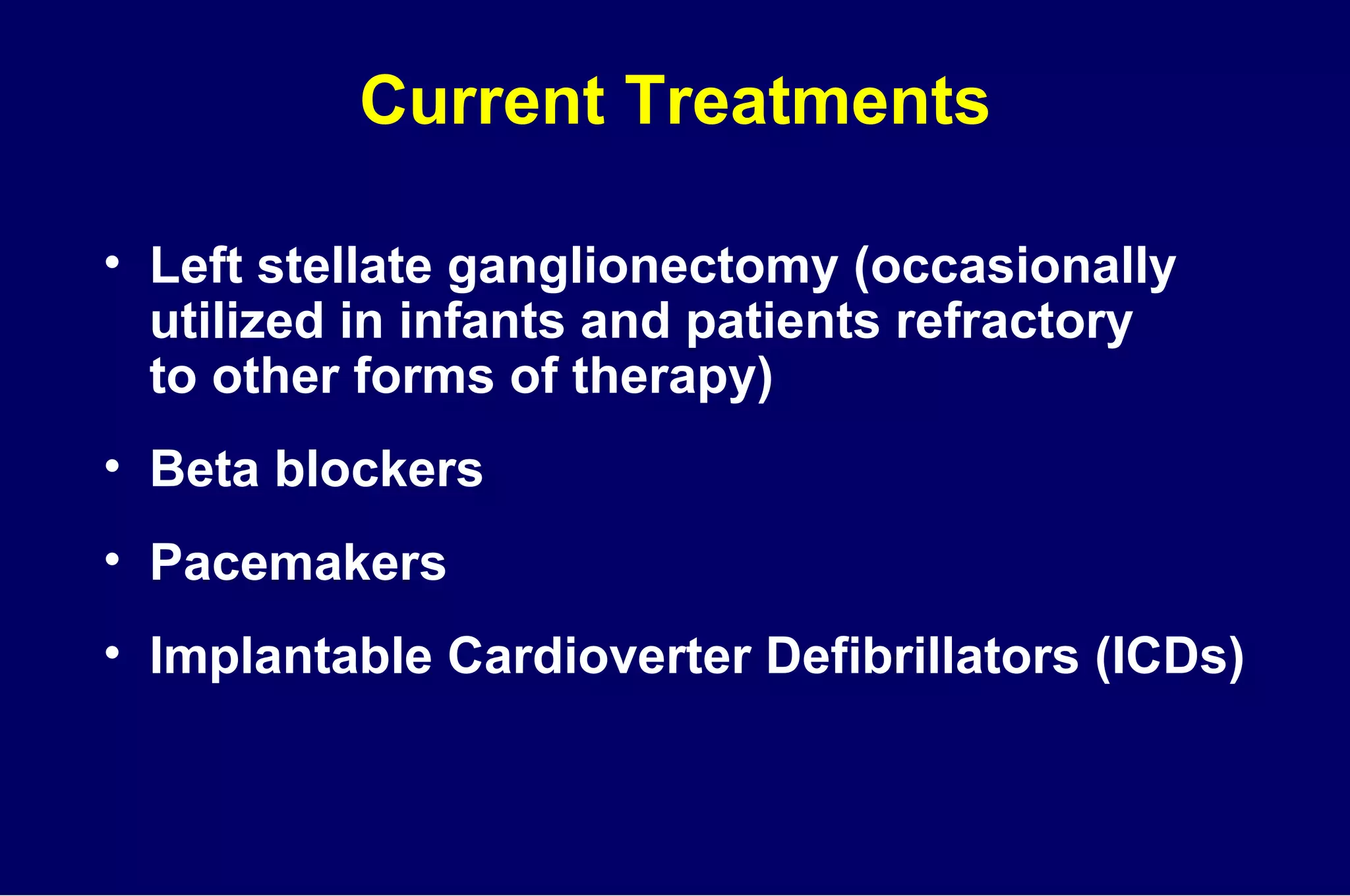

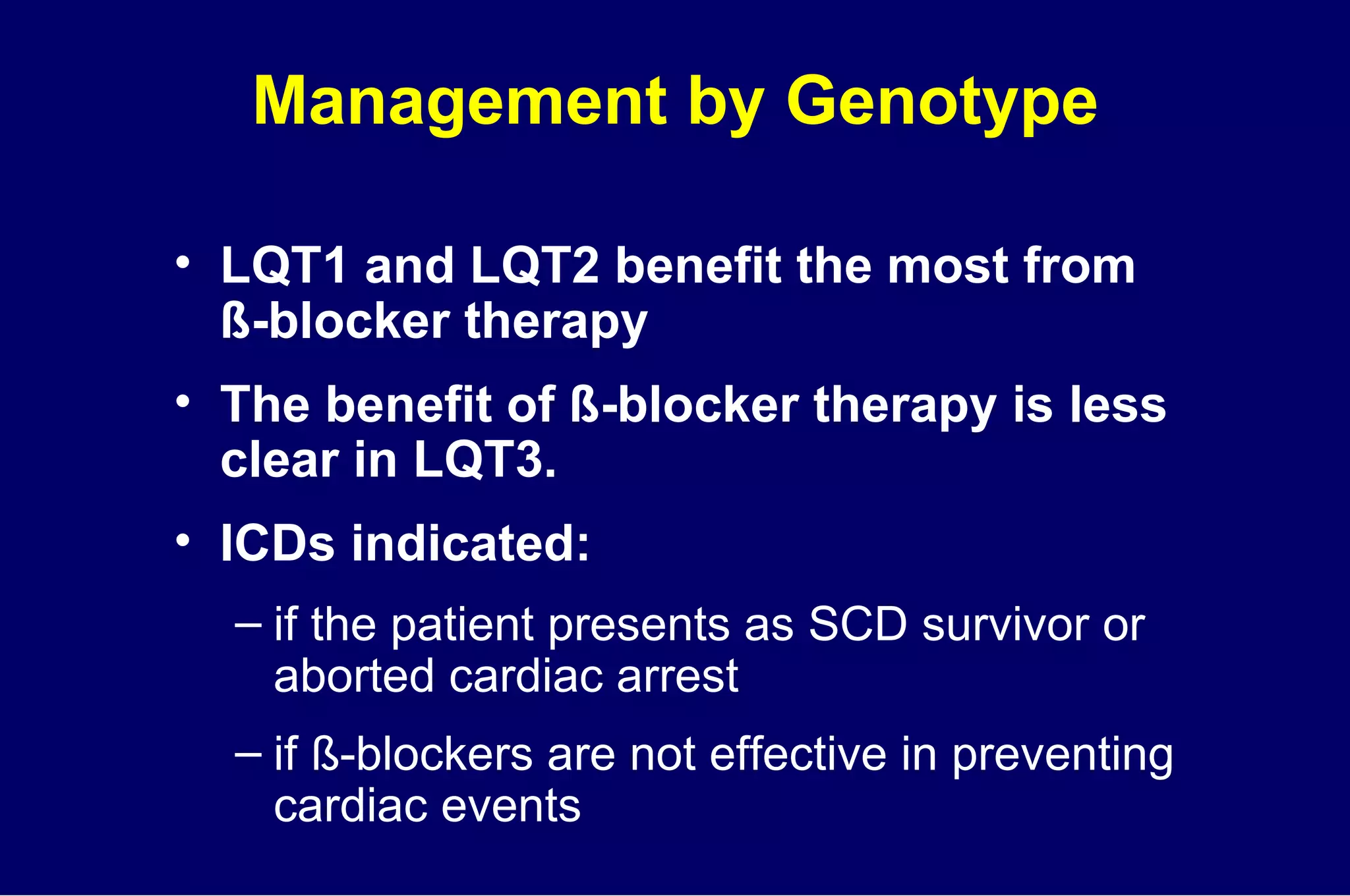

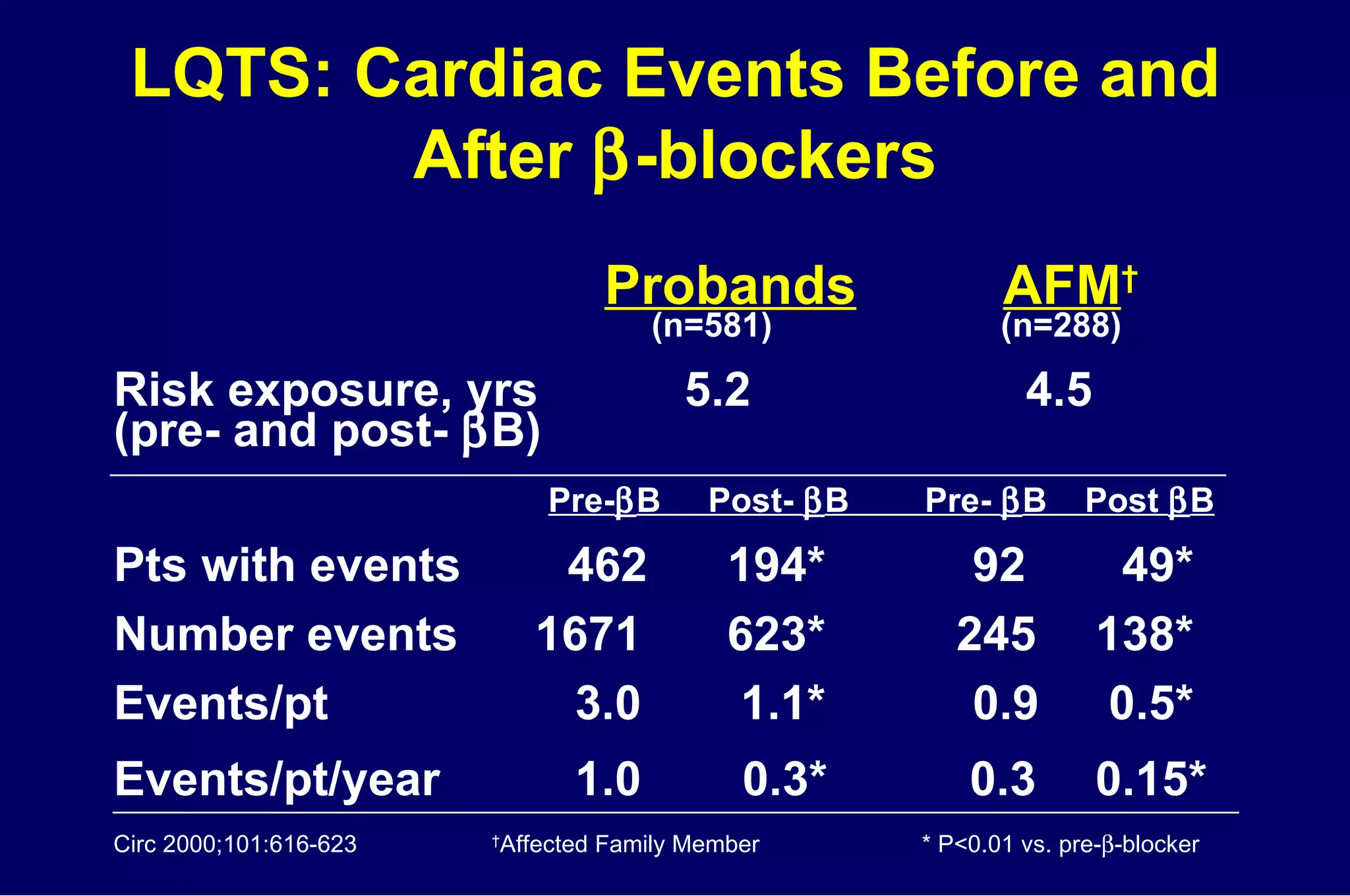

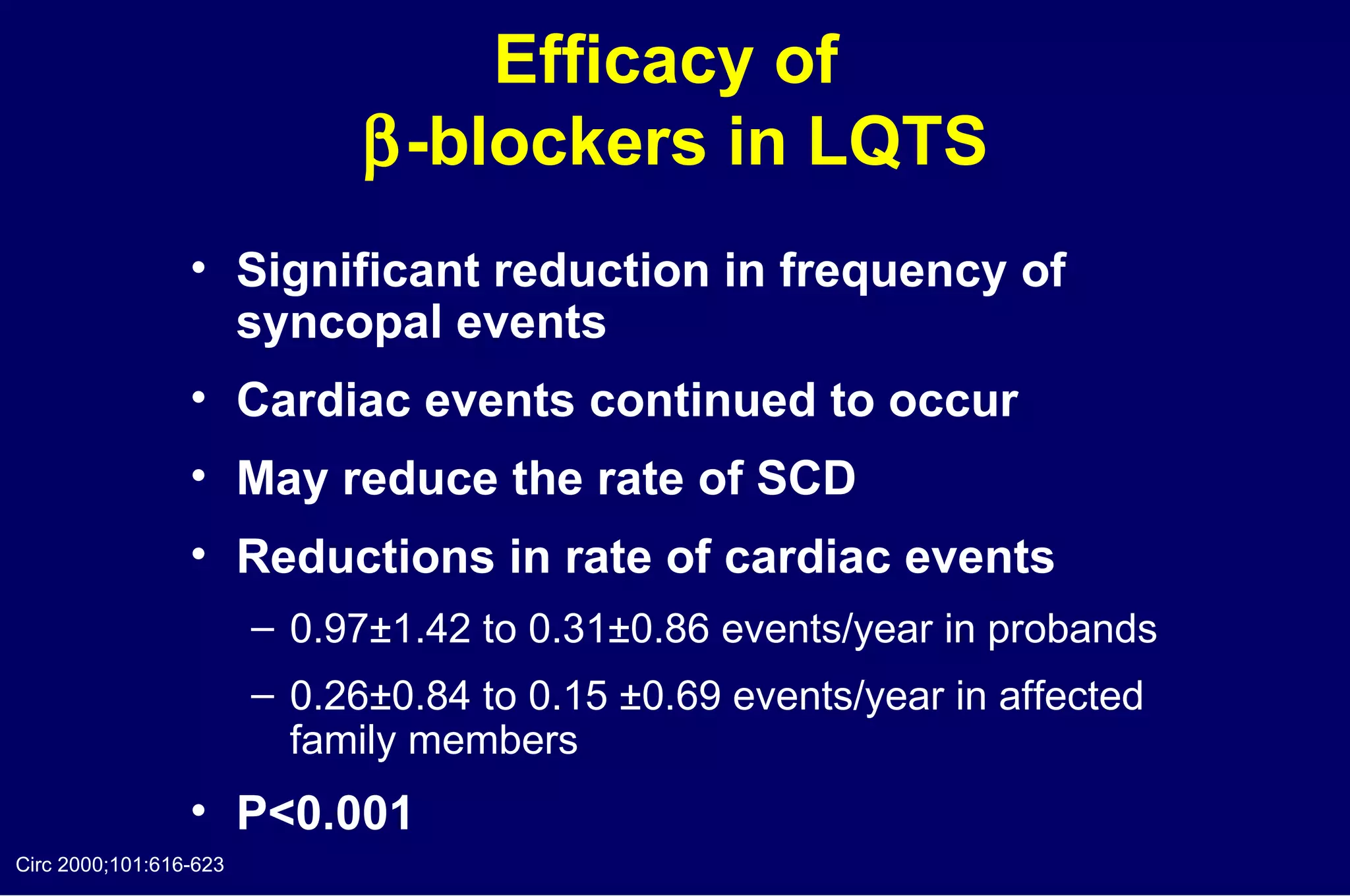

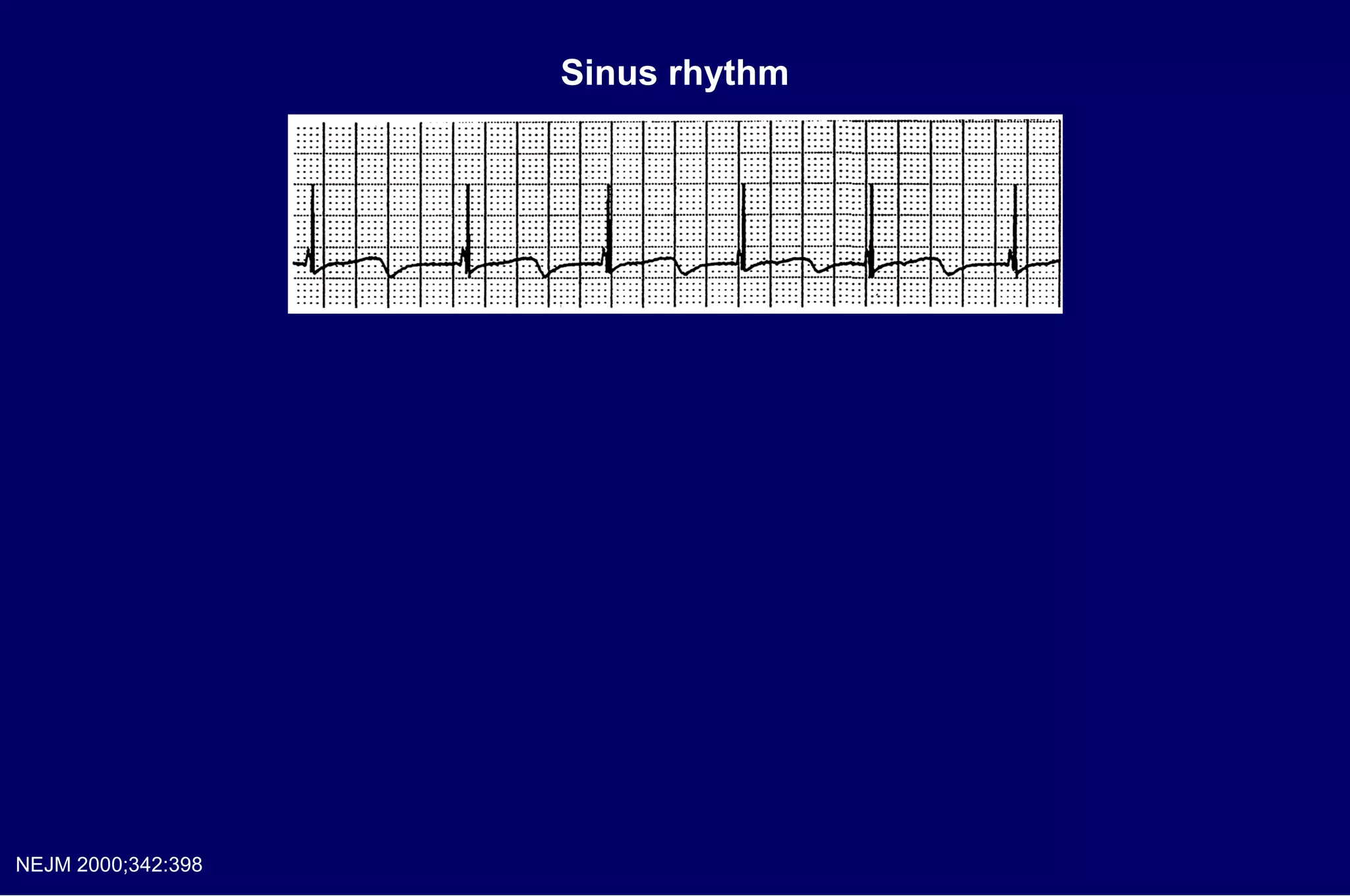

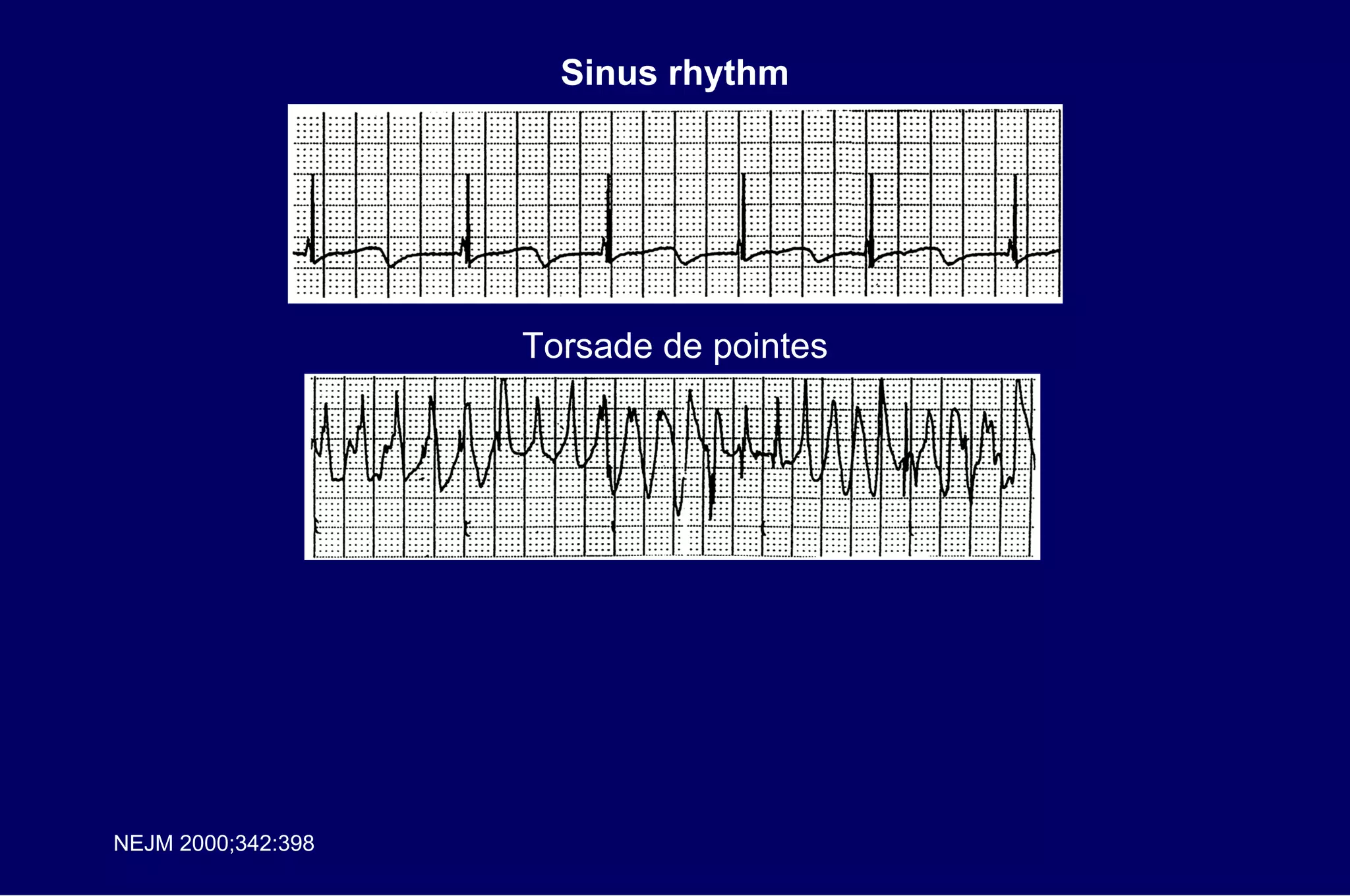

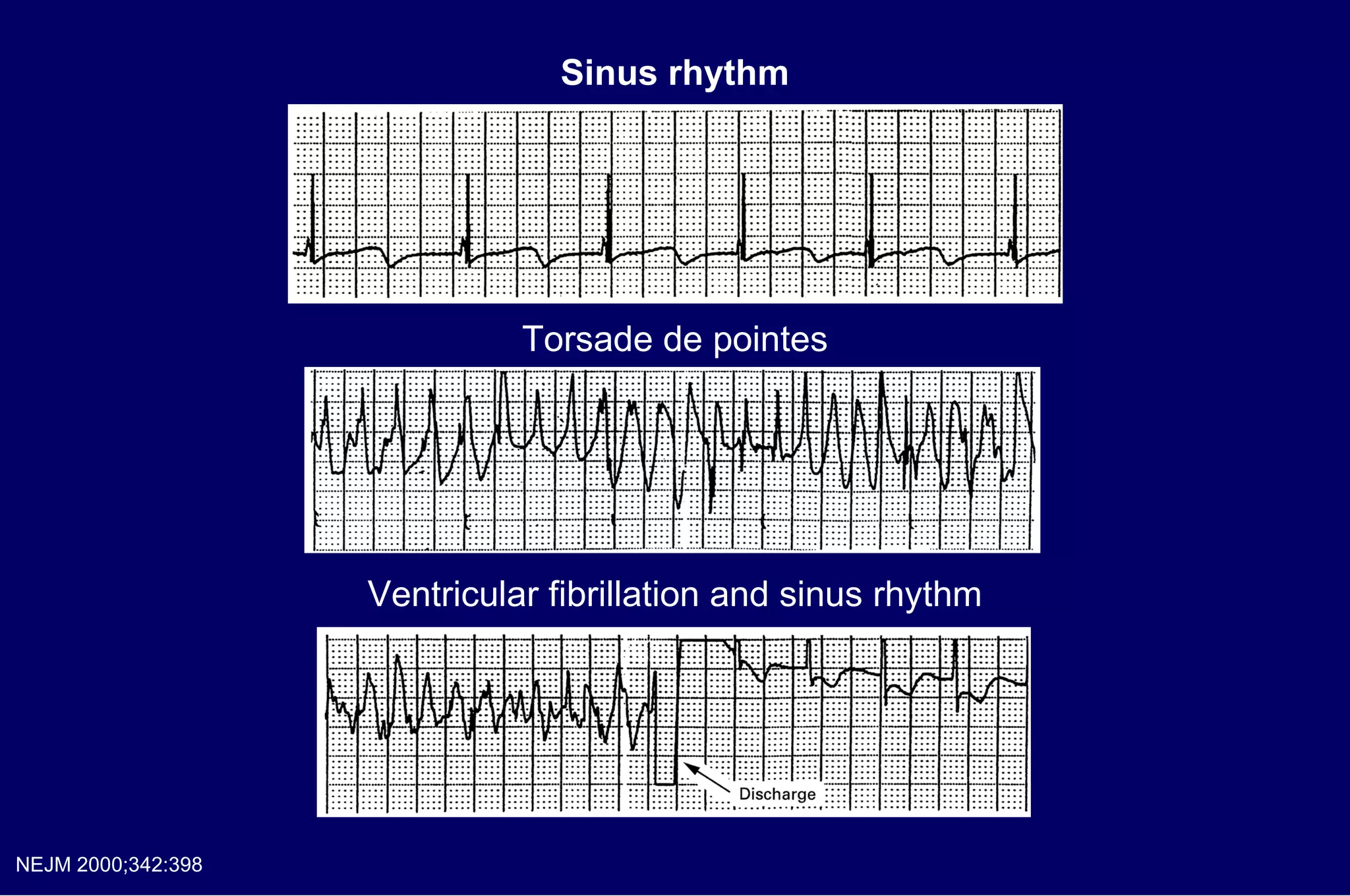

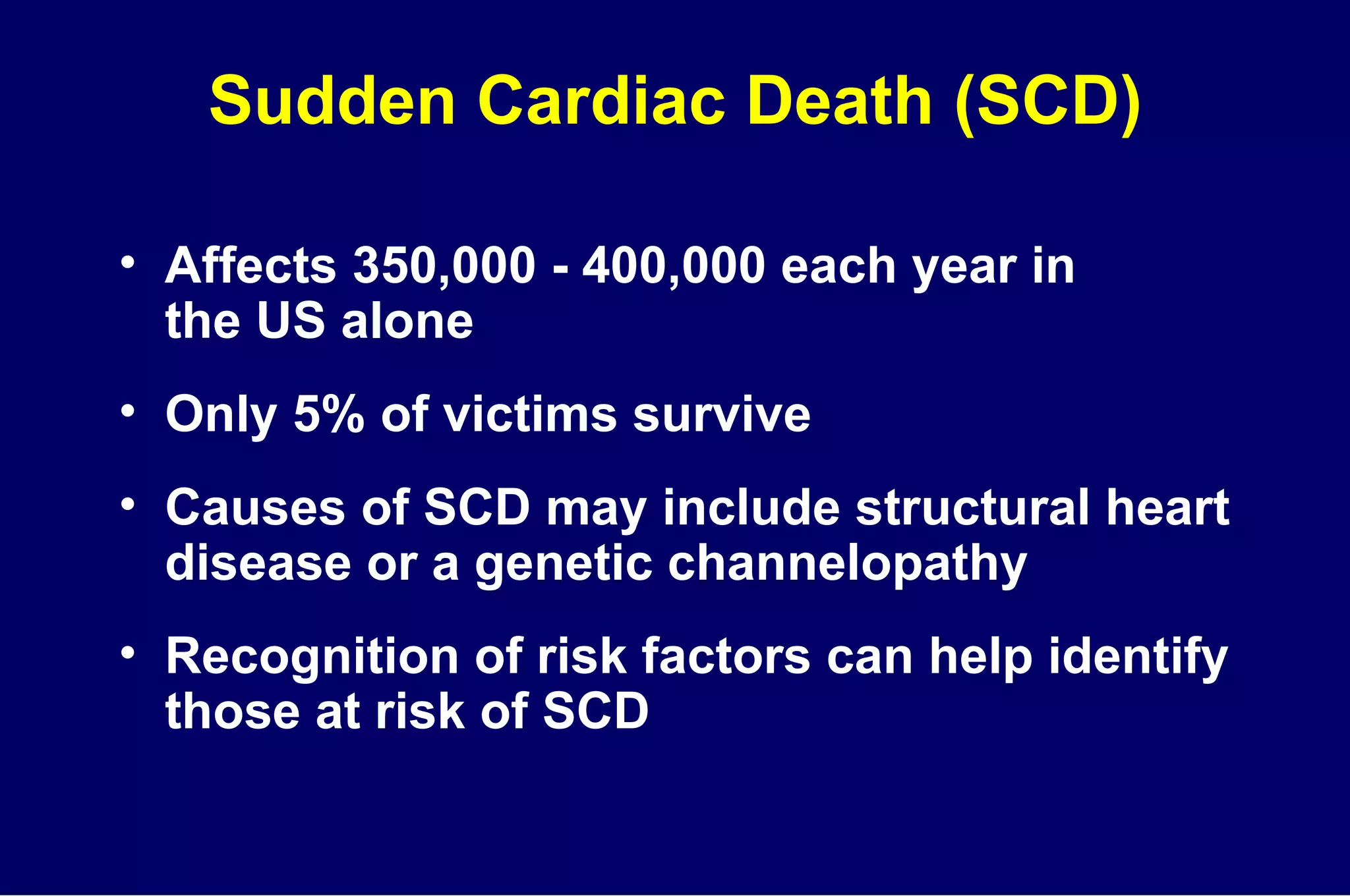

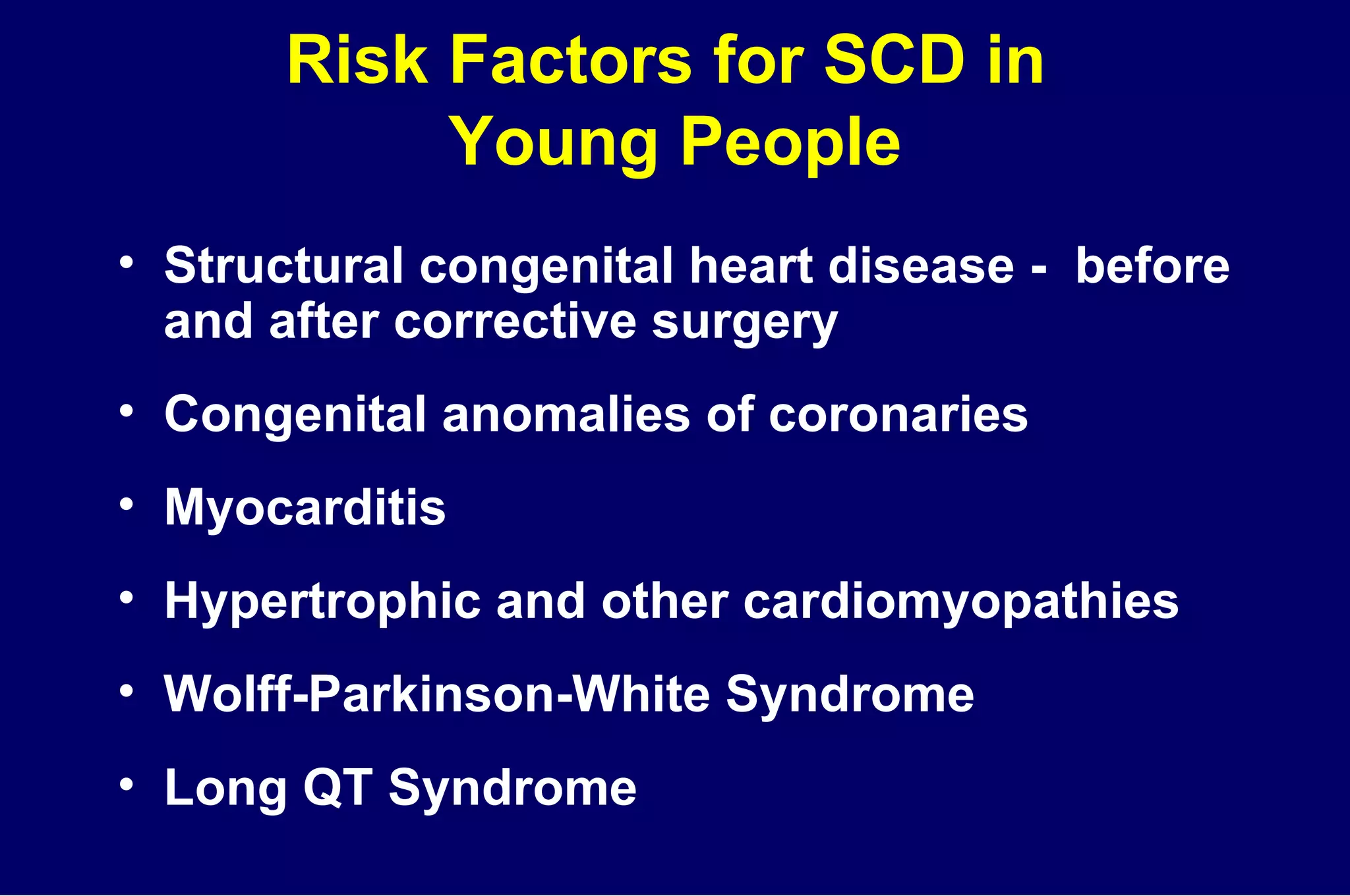

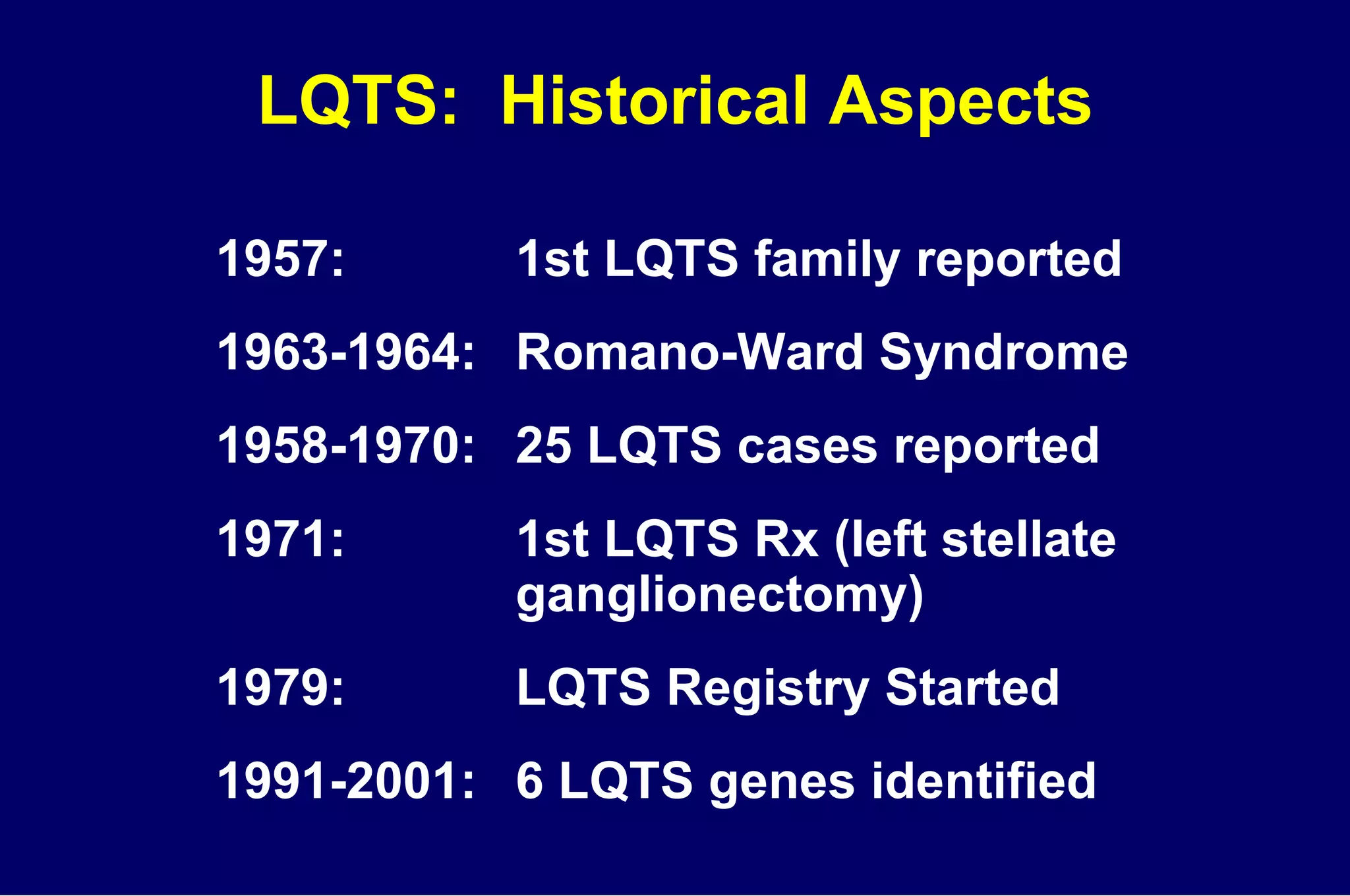

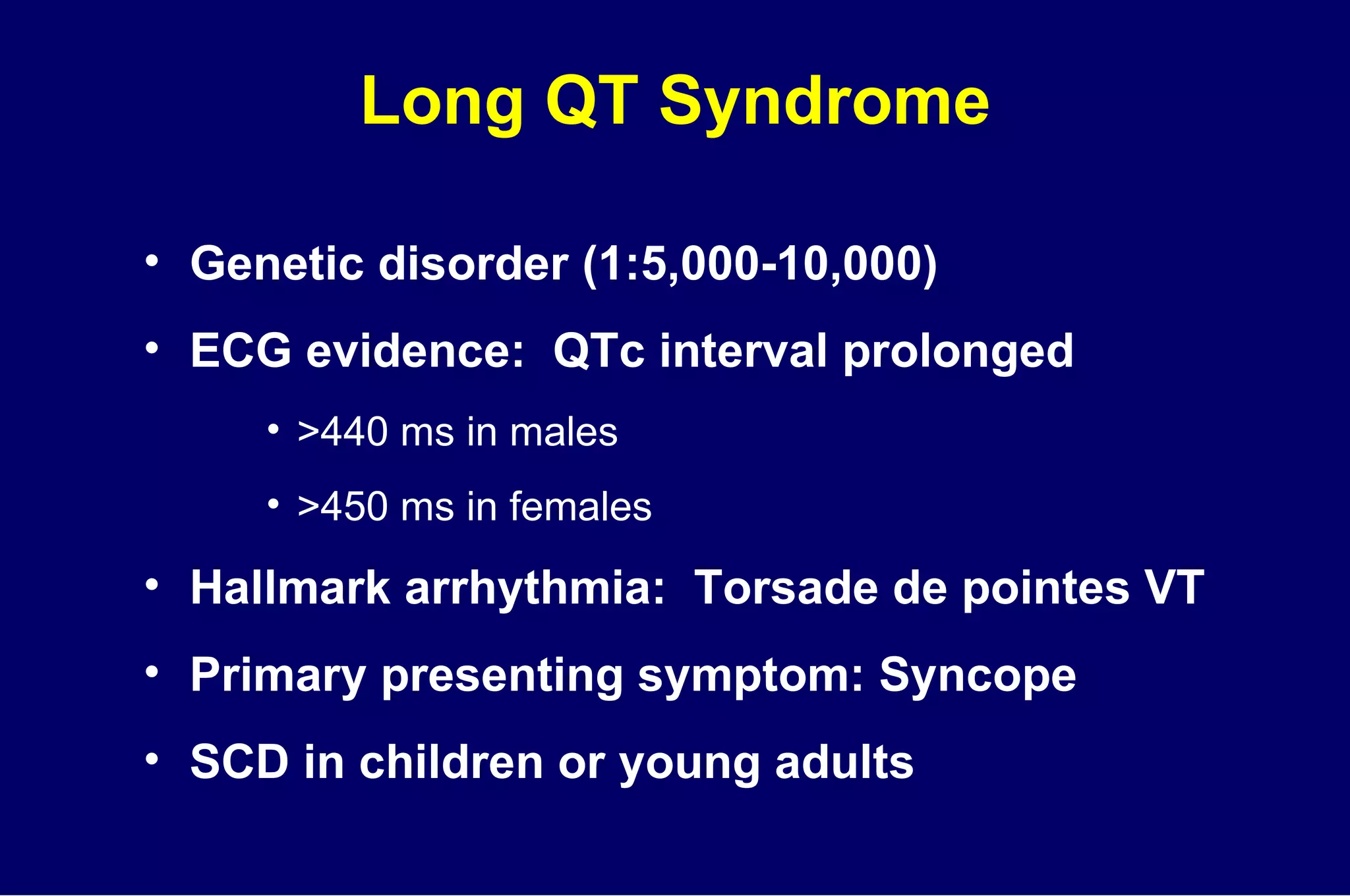

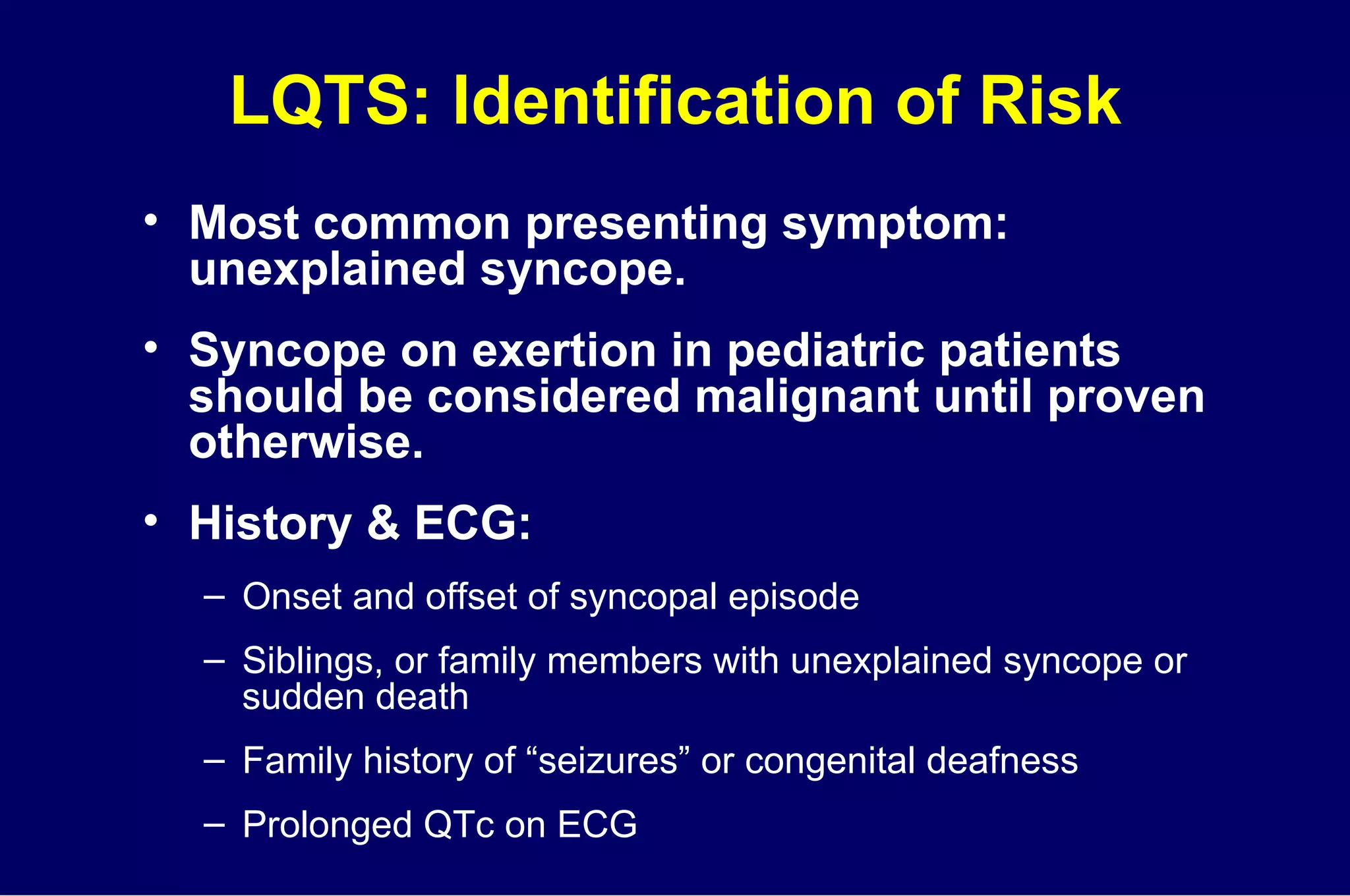

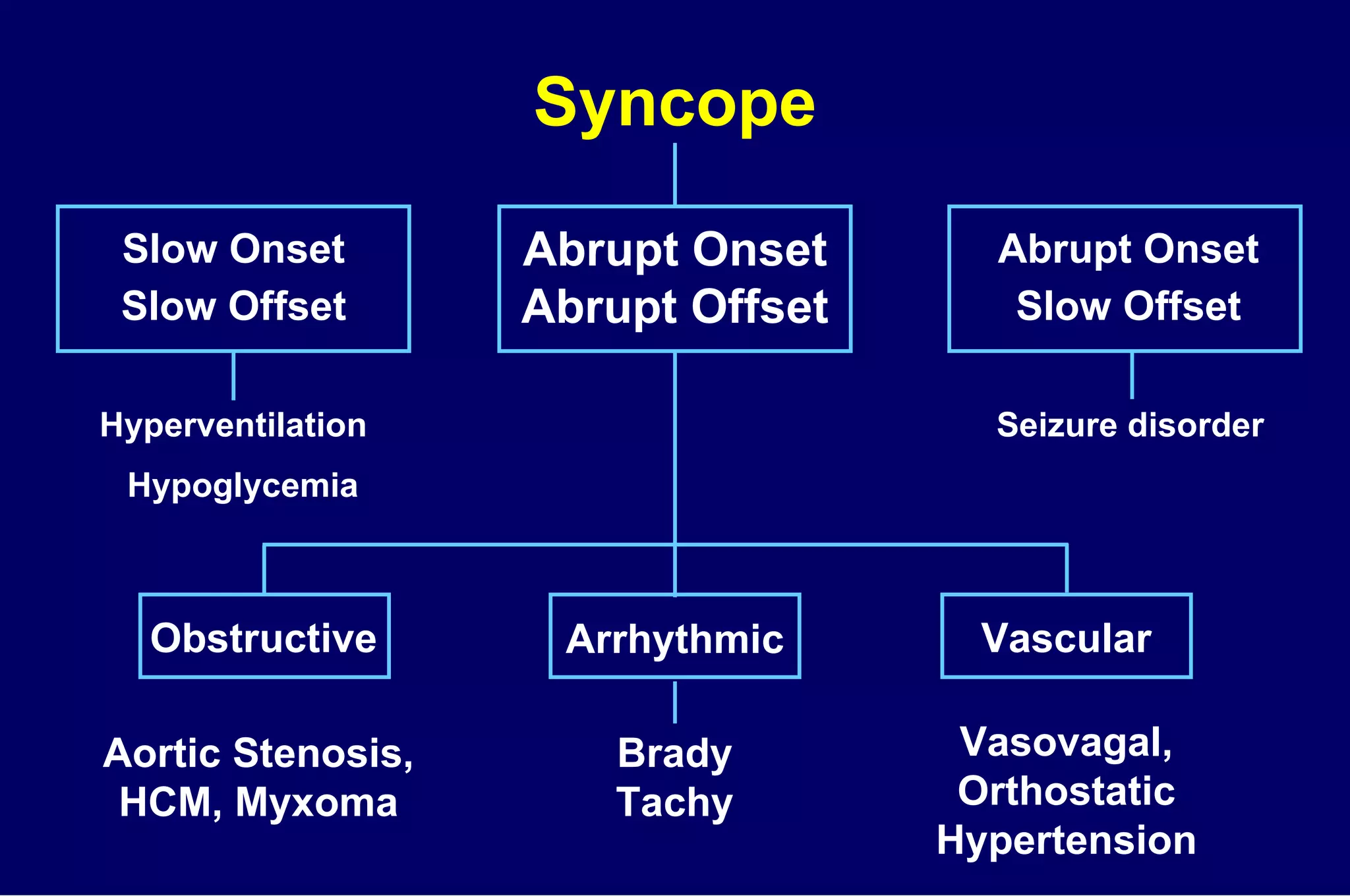

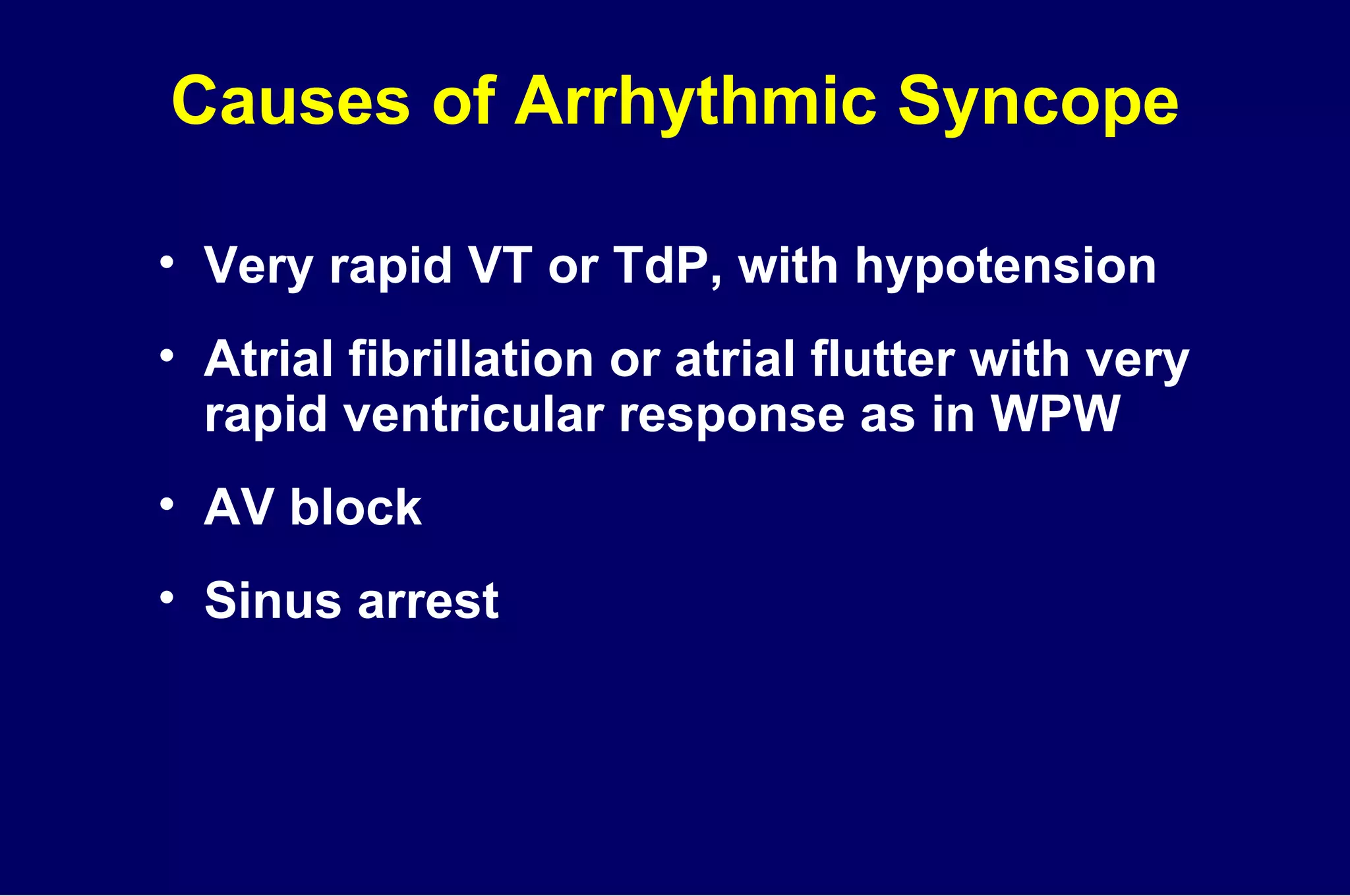

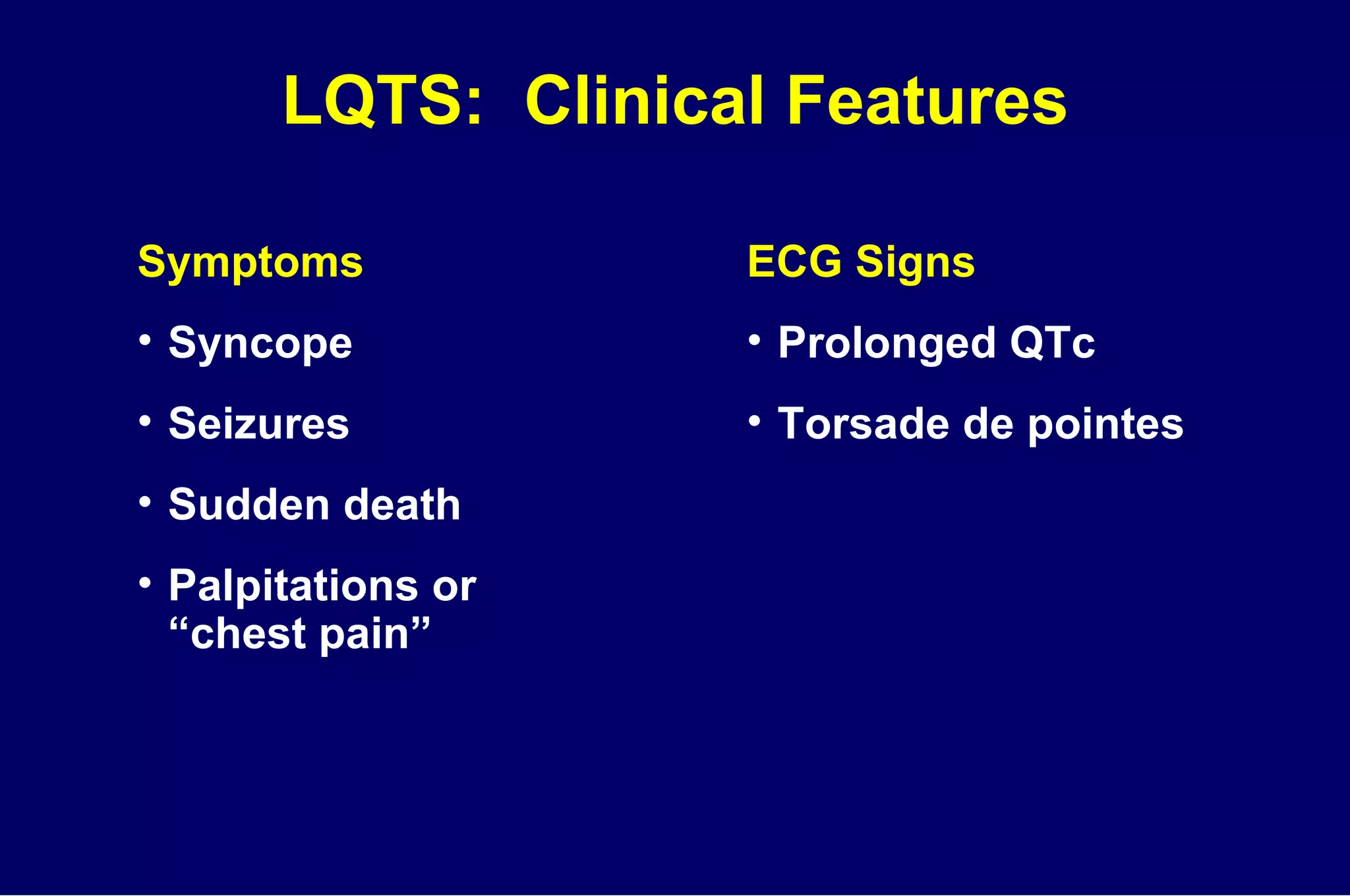

Long QT Syndrome is a genetic disorder characterized by a prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram that can cause dangerous arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Symptoms include unexplained fainting, seizures, or sudden death, especially with exercise or emotions. Treatment involves beta blockers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, or left stellate ganglionectomy depending on risk level and genotype. Ongoing research seeks to better understand genotype-phenotype relationships and develop mutation-specific therapies.

![LQTS ECG Patterns Circ 1992;85[Suppl I]:I140-I144](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/longqtsyn-1233754534676529-1/75/The-Long-QT-Syndrome-Overview-and-Management-The-Long-QT-Syndrome-Overview-and-Management-15-2048.jpg)

![Additional LQTS ECG Patterns Circ 1992;85[Suppl I]:I140-I144](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/longqtsyn-1233754534676529-1/75/The-Long-QT-Syndrome-Overview-and-Management-The-Long-QT-Syndrome-Overview-and-Management-16-2048.jpg)