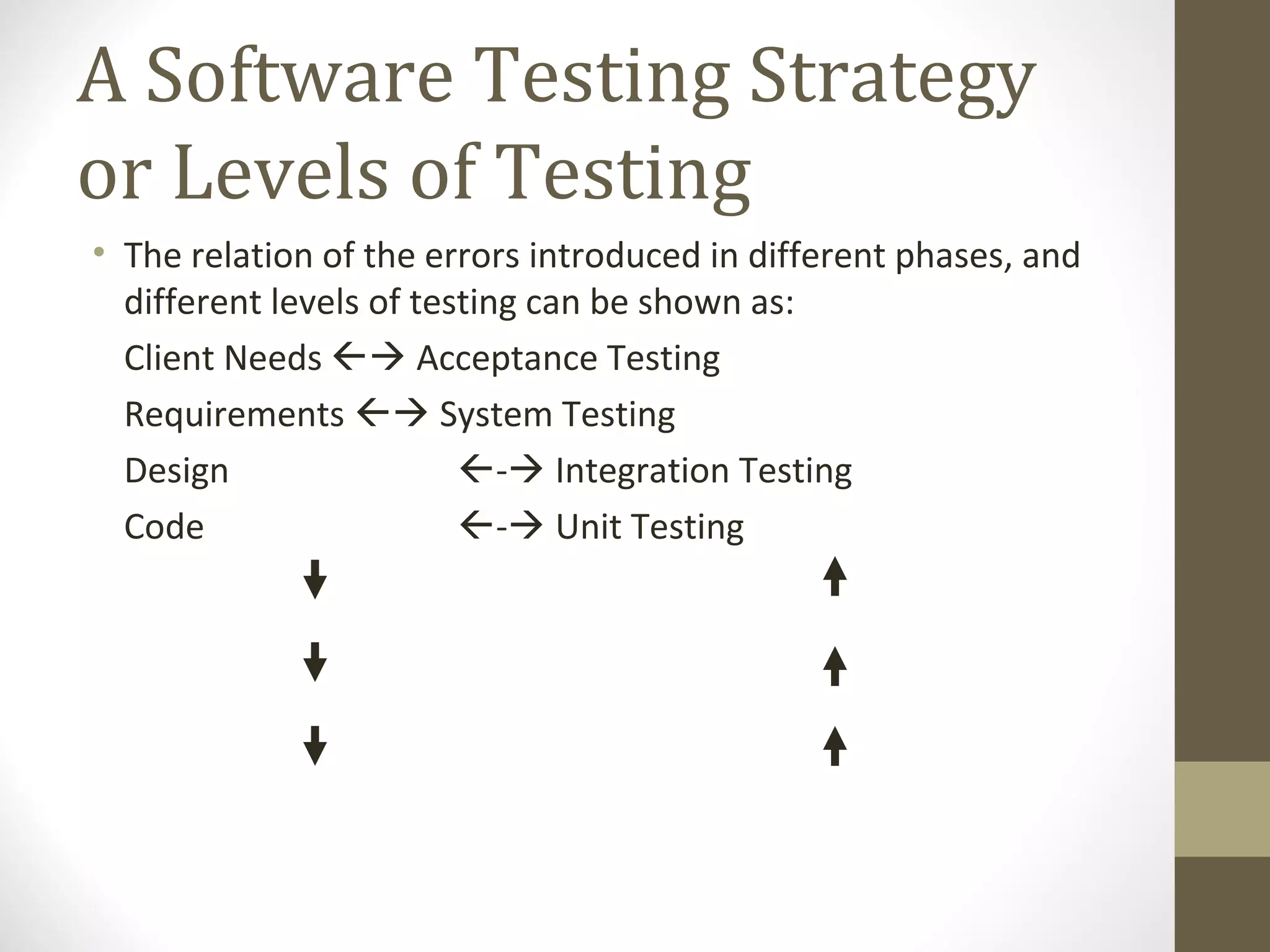

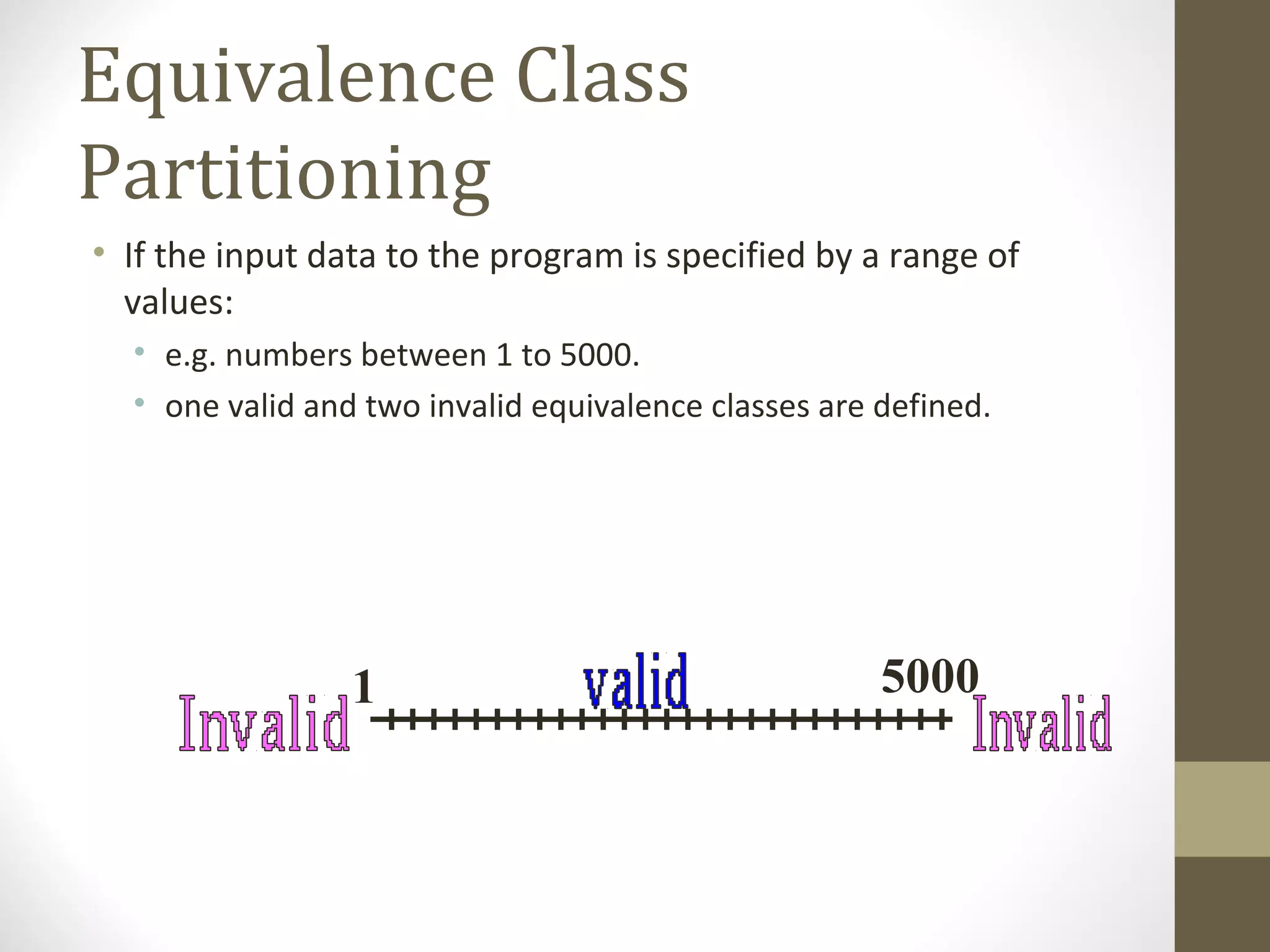

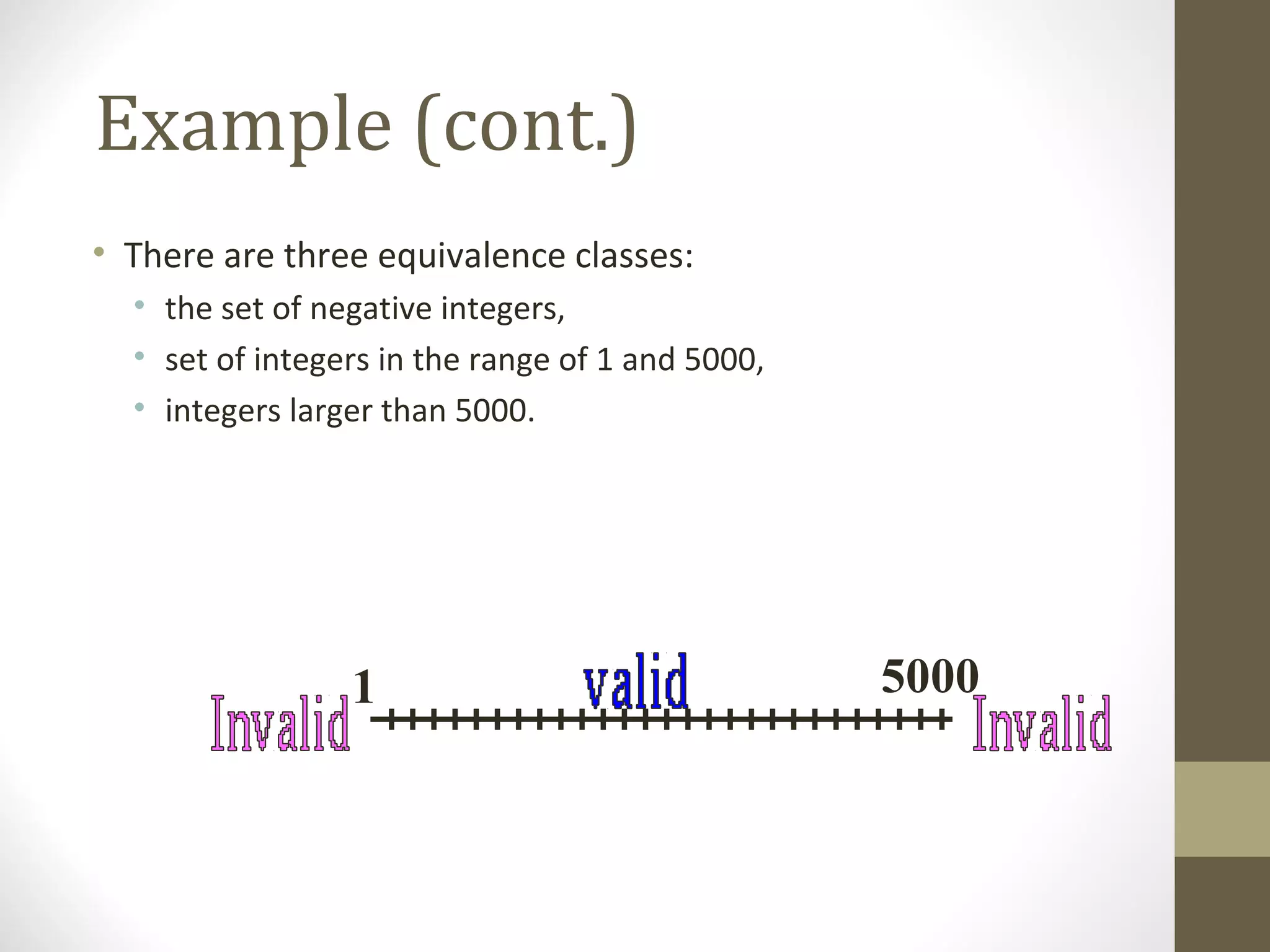

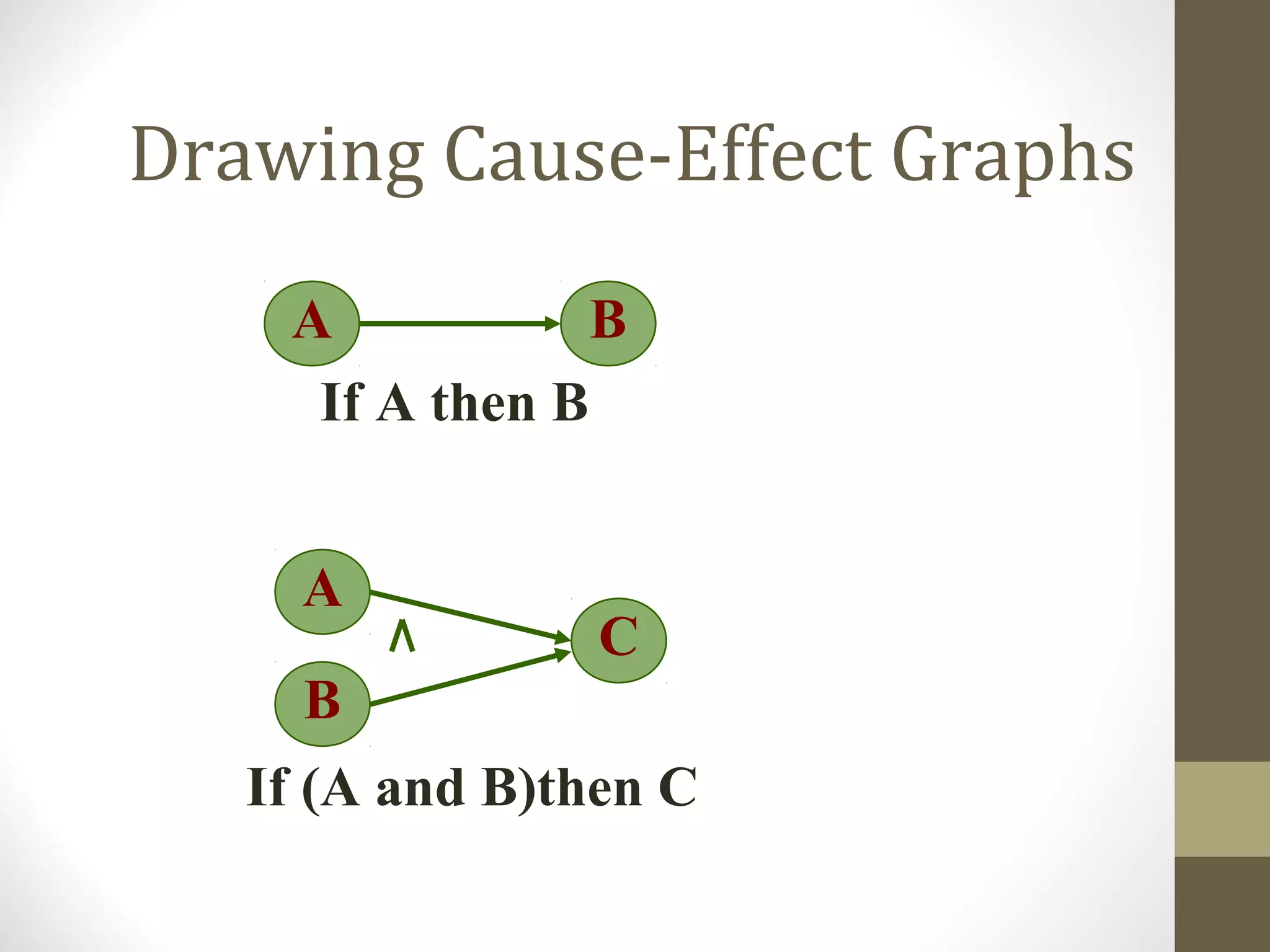

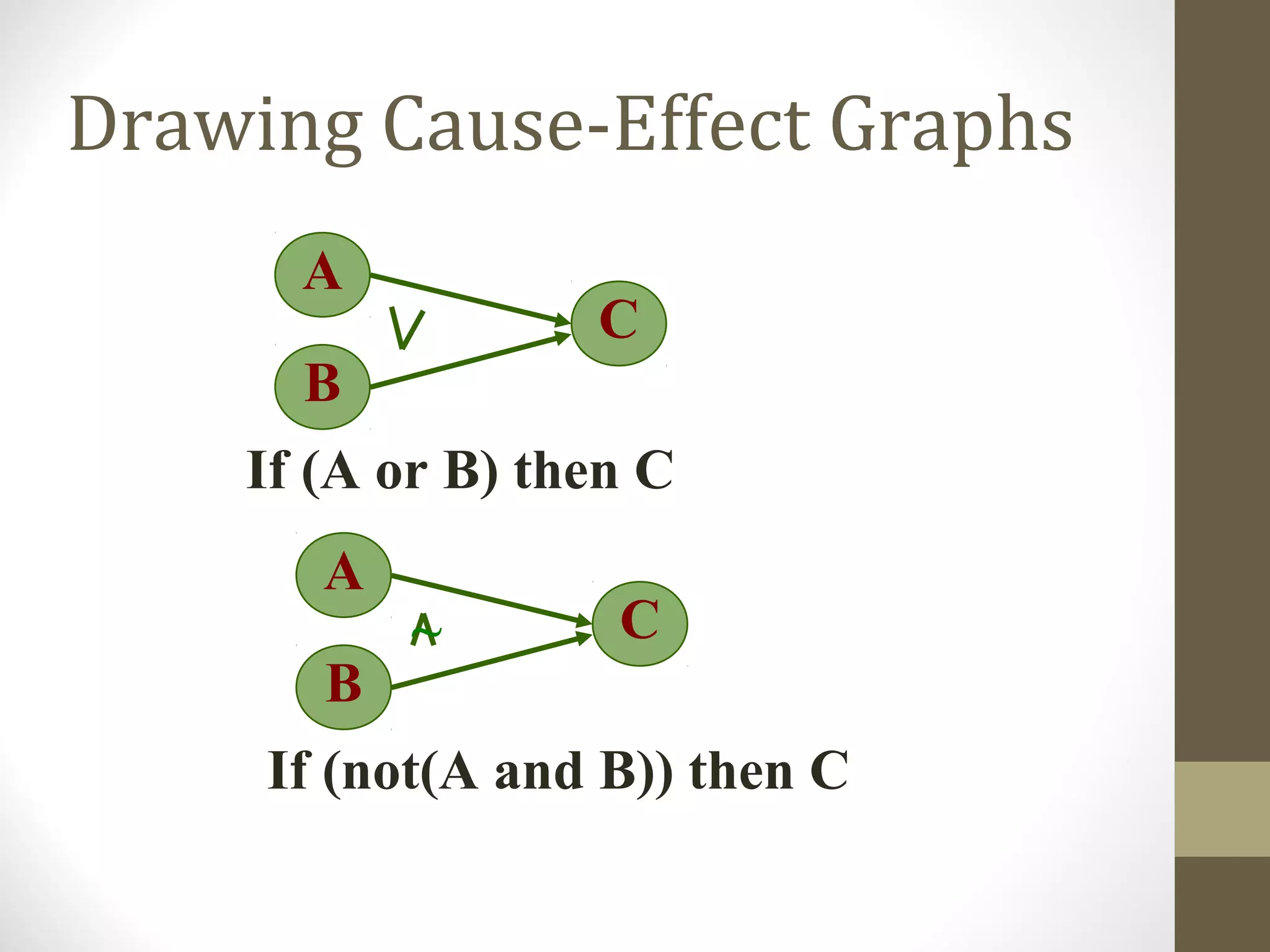

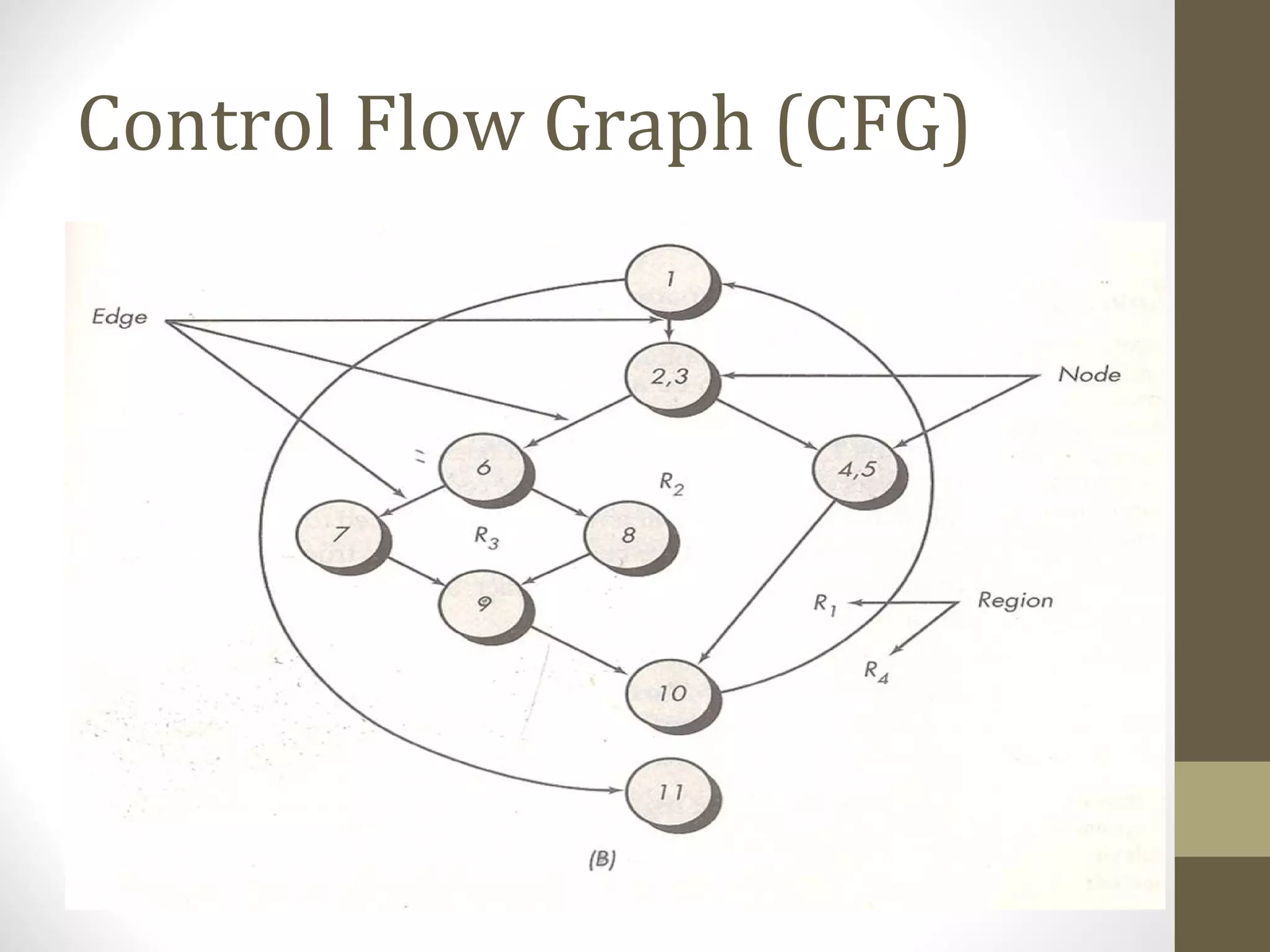

The document discusses various concepts related to software testing including verification vs validation, inspection vs testing, black box vs white box testing, and testing techniques like equivalence partitioning, boundary value analysis, and cause-effect graphing. It defines verification as ensuring software meets specifications while validation ensures it meets customer needs. Inspection examines static documents while testing evaluates dynamic behavior. Black box testing uses requirements while white box considers internal structure.