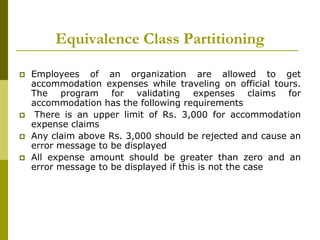

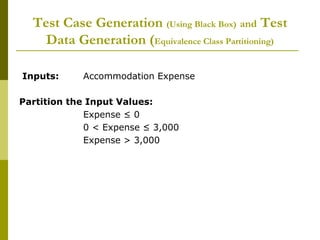

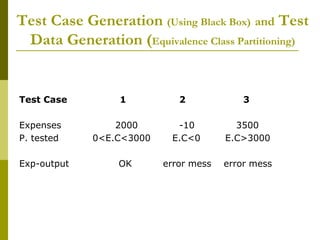

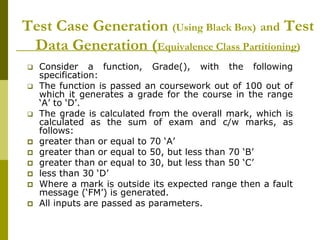

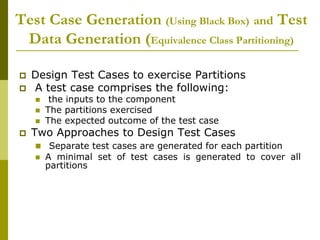

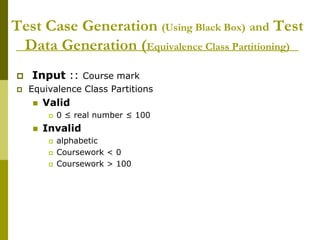

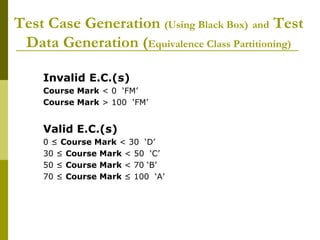

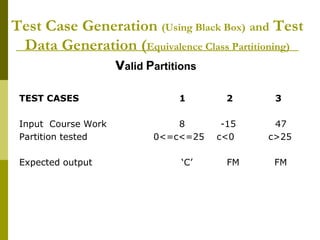

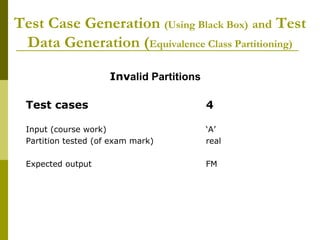

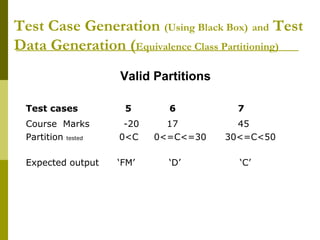

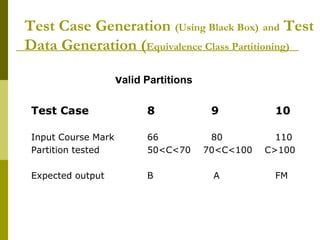

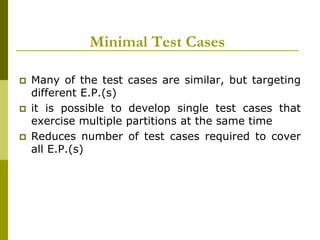

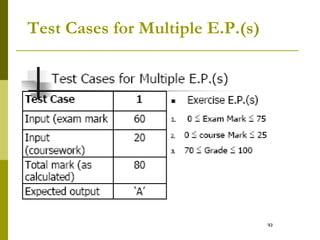

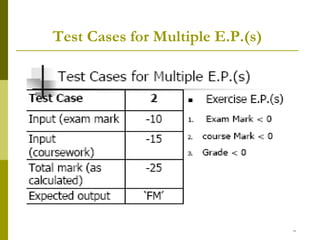

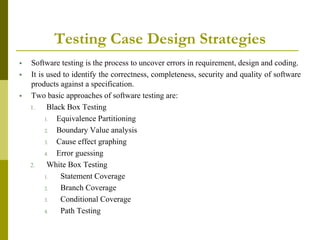

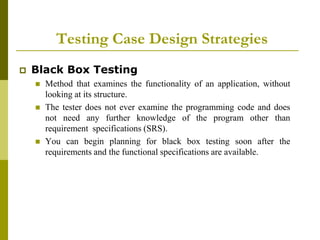

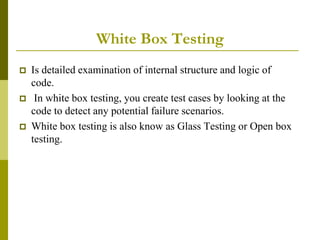

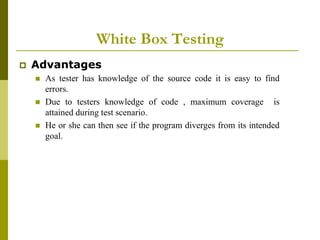

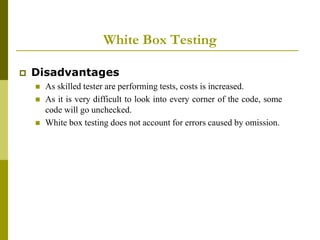

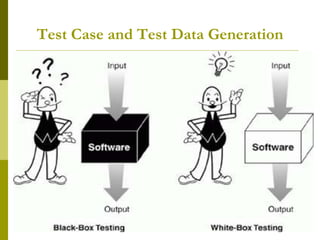

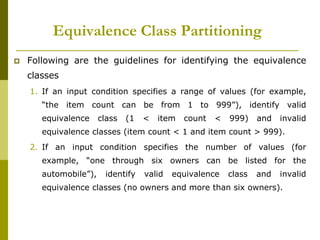

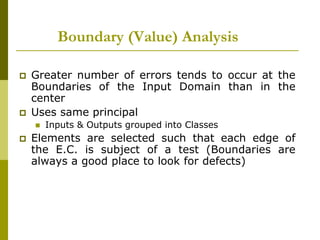

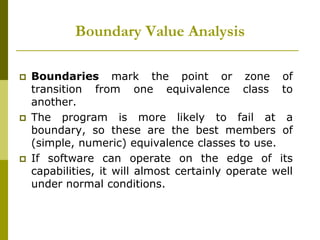

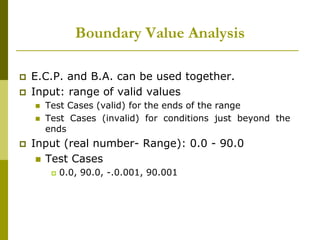

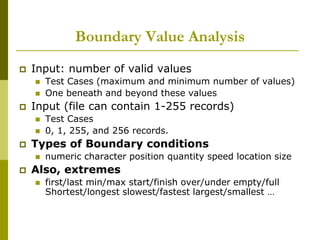

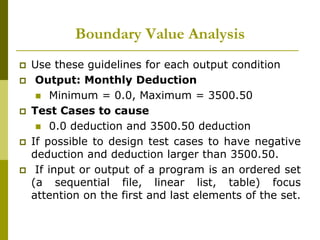

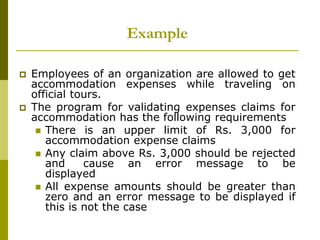

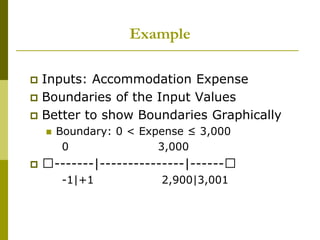

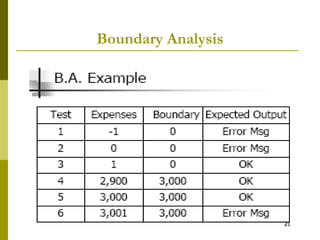

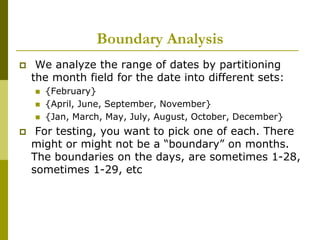

The document outlines software testing strategies, focusing on black box and white box testing approaches, including their advantages and disadvantages. It discusses test case generation techniques such as equivalence class partitioning and boundary value analysis, which help identify potential errors through systematic input categorization. Additionally, it presents practical examples and guidelines for designing test cases to ensure effective testing of software functionalities.

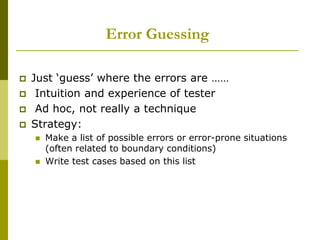

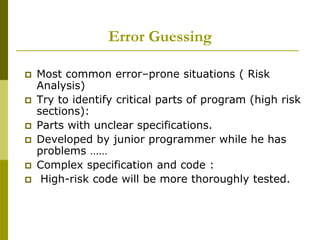

![Error Guessing

Defects’ histories are useful

Some items to try are:

Empty or null lists/strings

Zero instances/occurrences

Blanks or null characters in strings

Negative numbers

“Probability of errors remaining in the program is

proportional to the number of errors that have

been found so far” [Myers 79]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/blackbox-191116054136/85/Black-Box-Testing-27-320.jpg)