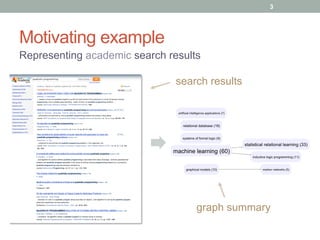

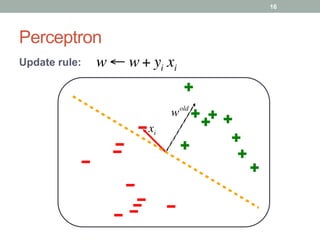

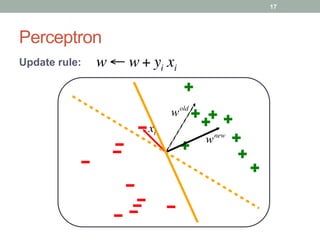

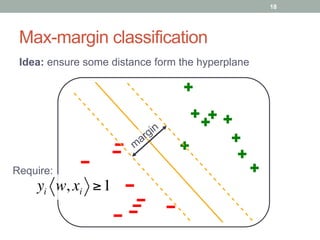

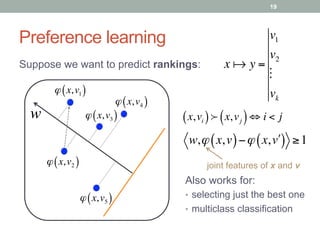

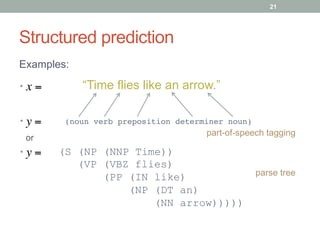

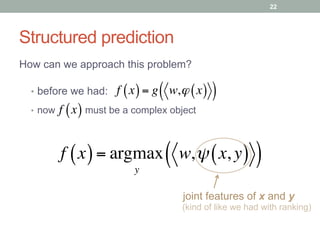

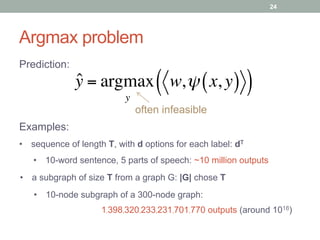

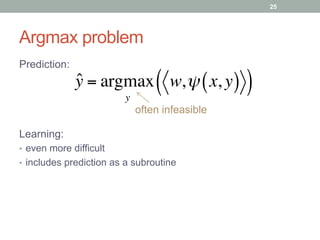

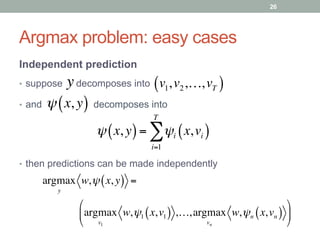

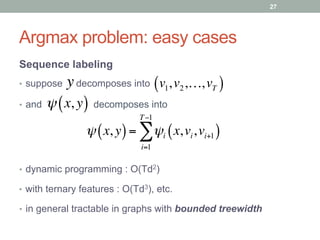

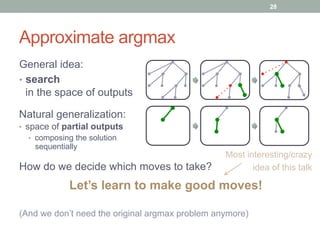

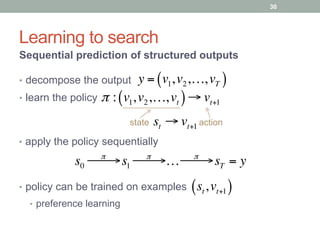

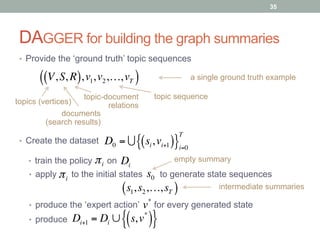

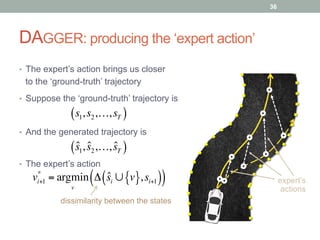

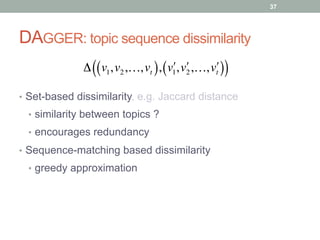

The document discusses the supervised prediction of graph summaries, focusing on various machine learning techniques such as binary classification, ranking, and structured output prediction. It highlights methods like the perceptron algorithm, structured perceptron, and learning to search through approaches like SEARN and DAgger for efficient predictions and decision-making in complex structured outputs. The conclusion outlines how these techniques can apply to fine-tuning predictions based on ground truth representations in graph summarization tasks.

![Searn and DAGGER

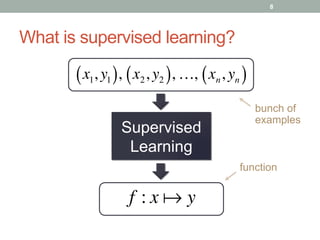

Searn = “search” + “learn”

• start from optimal policy;

move away

• generate new states with current

• generate actions based on regret

• train on new state-action pairs

• interpolate the current policy

πi+1 ← βπi + 1− β( ) #πi+1

policy learnt at ith iteration

regret

32

[1] Hal Daumé III, John Langford, Daniel Marcu. Search-based Structured Prediction. Machine Learning Journal, 2006.

[1]

!πi+1

πi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/supervisedpredictionofgraphsummariesgoogle-141018062403-conversion-gate01/85/Supervised-Prediction-of-Graph-Summaries-32-320.jpg)

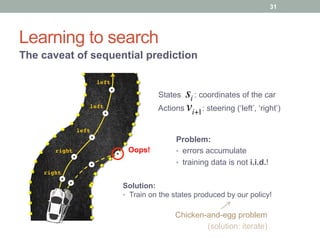

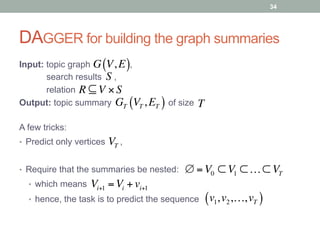

![Searn and DAGGER

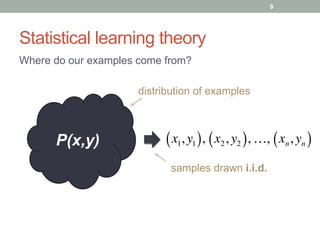

DAGGER = “dataset” + “aggregation”

• start from the ‘ground truth’ dataset,

enrich it with new state-action pairs

• train a policy on the current dataset

• use the policy to generate new states

• generate ‘expert’s actions’ for new states

• add new state-action pairs to the dataset

expert’s

actions

As in Searn, we’ll eventually be training

on our own-produced states

33

[2] Stephane Ross, Geoffrey Gordon, Drew Bagnell. A reduction of imitation learning and

structured prediction to no-regret online learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2011.

[2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/supervisedpredictionofgraphsummariesgoogle-141018062403-conversion-gate01/85/Supervised-Prediction-of-Graph-Summaries-33-320.jpg)

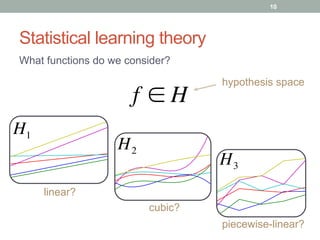

![DAGGER: topic graph features

• Coverage and diversity

• [transitive] document coverage

• [transitive] topic frequency, average and min

• topic overlap, average and max

• parent-child overlap, average and max

• …

38

ψ V,S, R( ), v1,v2,…,vt( )( )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/supervisedpredictionofgraphsummariesgoogle-141018062403-conversion-gate01/85/Supervised-Prediction-of-Graph-Summaries-38-320.jpg)

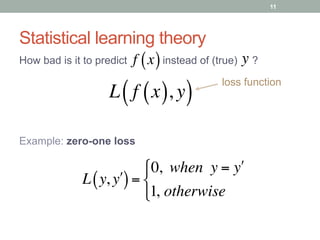

![Support Vector Machine

Idea: large margin between positive and negative examples

Loss function:

L y, f x( )( )=[1− y⋅ f x( )]+

Hinge loss

(solved by constrained convex optimization)

yi w, xi ≥ C

C → max

#

$

%

&%

⇔

yi w, xi ≥1

w → min

#

$

%

&%

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/supervisedpredictionofgraphsummariesgoogle-141018062403-conversion-gate01/85/Supervised-Prediction-of-Graph-Summaries-42-320.jpg)