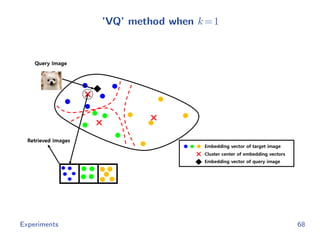

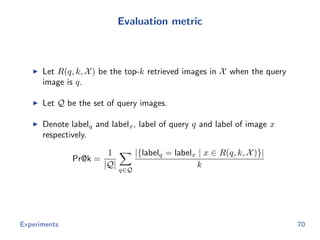

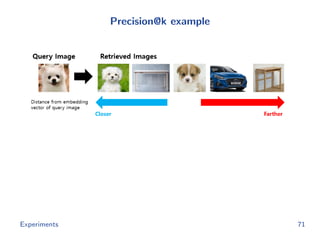

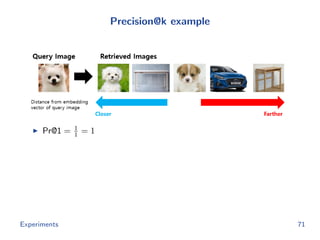

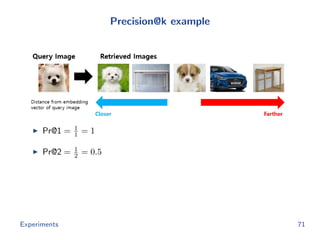

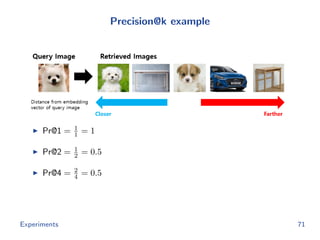

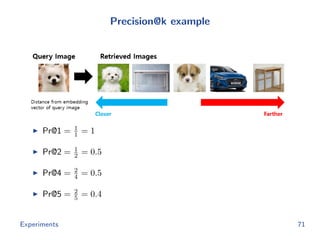

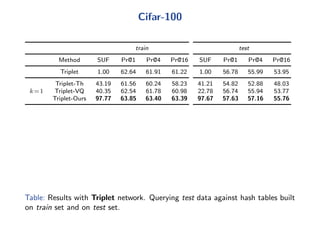

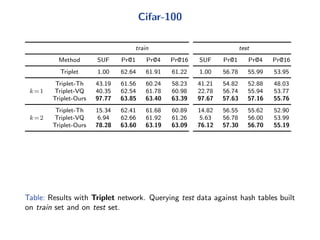

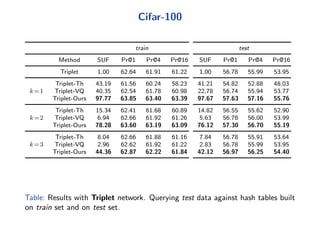

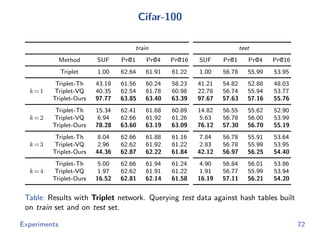

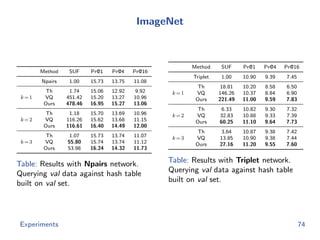

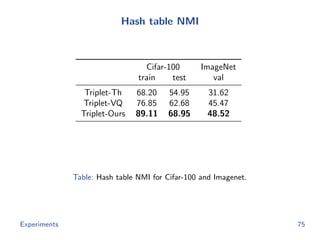

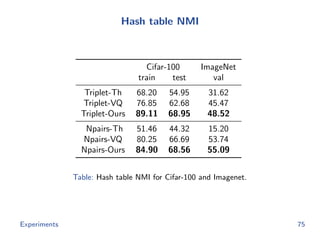

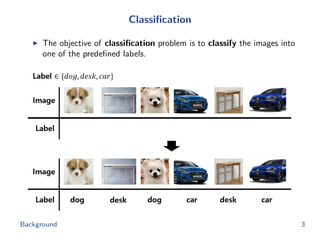

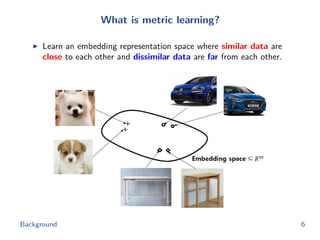

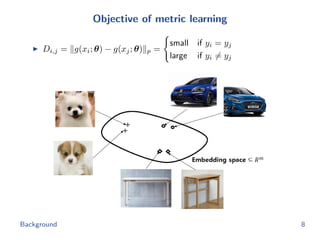

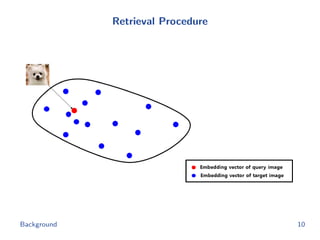

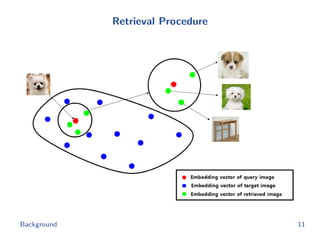

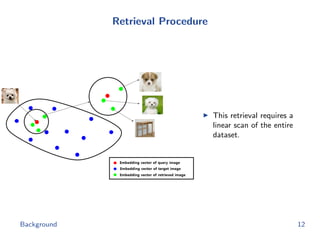

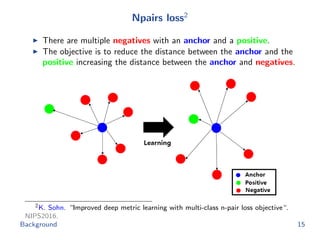

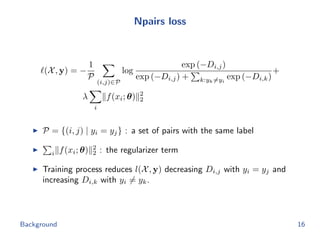

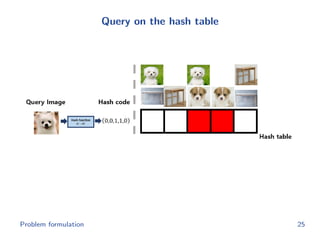

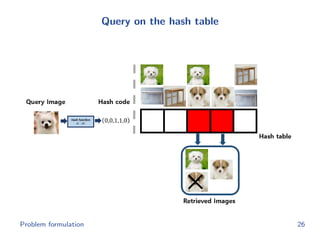

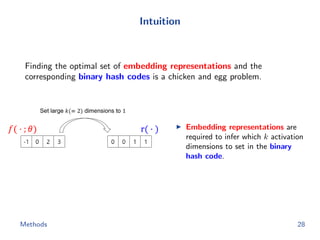

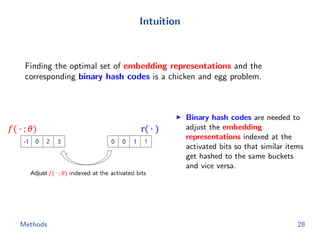

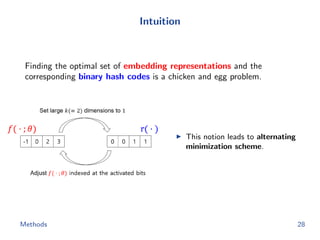

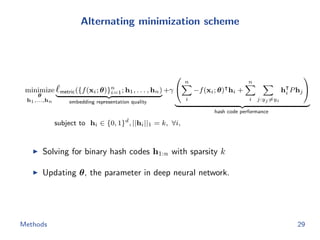

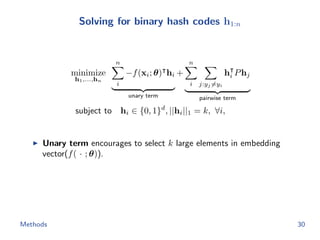

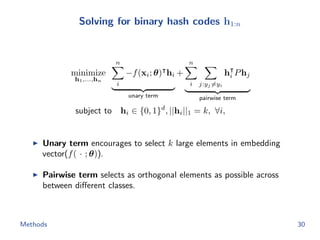

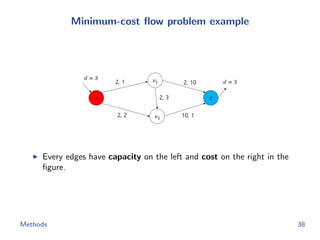

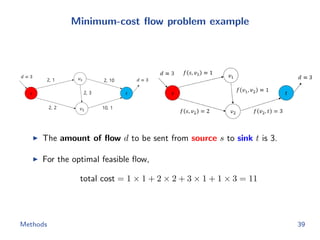

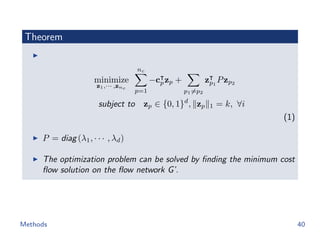

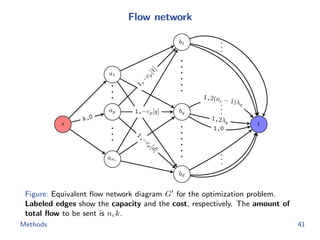

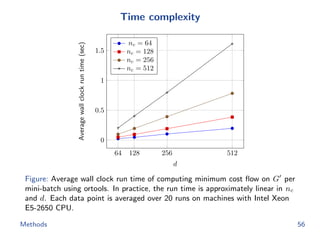

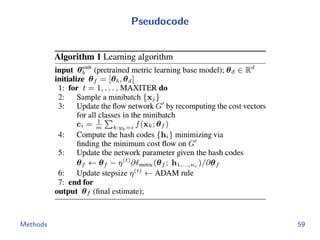

The document discusses efficient end-to-end learning for quantizable representation, focusing on the challenges of image classification with numerous labels and the role of metric learning in addressing these challenges. It presents various methods, including triplet loss and npairs loss, to optimize embedding representations and corresponding binary hash codes, utilizing an alternating minimization framework. The document also outlines experiments comparing proposed methods against baseline approaches to evaluate performance.

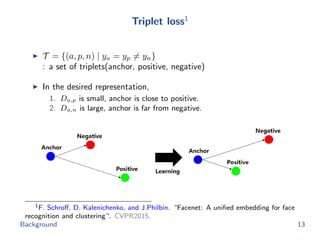

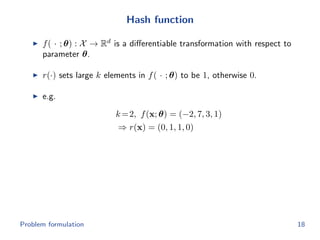

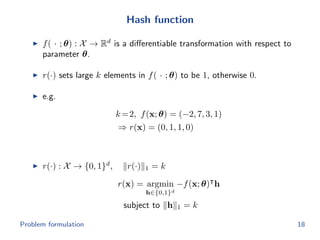

![Triplet loss

(X, y) =

1

T

(a,p,n)∈T

[D2

a,p + α − D2

a,n]+

X : a set of images

y : a set of classes

T : a set of triplets(anchor, positive, negative)

α : a margin which is constant

[·]+ = max(·, 0)

Training process reduces l(X, y) decreasing Da,p and increasing Da,n.

Background 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-180928092811/85/Efficient-end-to-end-learning-for-quantizable-representations-14-320.jpg)

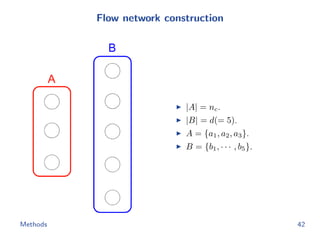

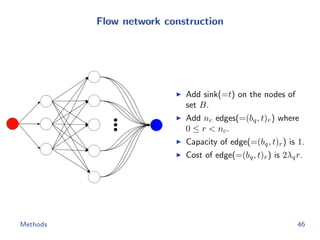

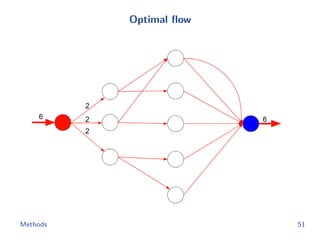

![Flow network construction

c1 = (1, 2, −1, 3, −2)

Capacity of every edge is 1.

Cost of edge(=(ap, bq)) is

−cp[q].

Methods 43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-180928092811/85/Efficient-end-to-end-learning-for-quantizable-representations-52-320.jpg)

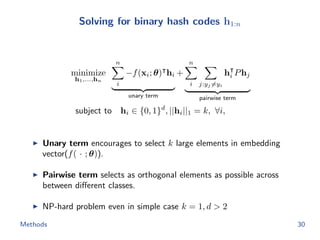

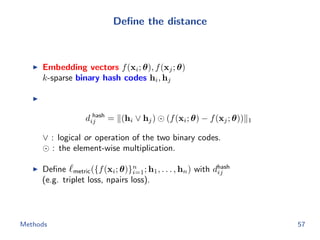

![Metric learning losses

Triplet loss

minimize

θ

1

|T |

(i,j,k)∈T

[d hash

ij + α − d hash

ik ]+

triplet(θ; h1,...,n)

subject to ||f(x; θ)||2 = 1

We apply the semi-hard negative mining to construct triplet.

Npairs loss

minimize

θ

−1

|P|

(i,j)∈P

log

exp(−d hash

ij )

exp(−d hash

ij ) + k:yk=yi

exp(−d hash

ik )

npairs(θ; h1,...,n)

+

λ

m i

||f(xi; θ)||2

2

Methods 58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-180928092811/85/Efficient-end-to-end-learning-for-quantizable-representations-69-320.jpg)

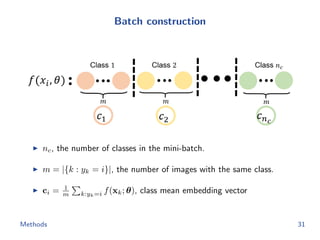

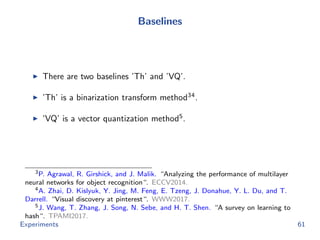

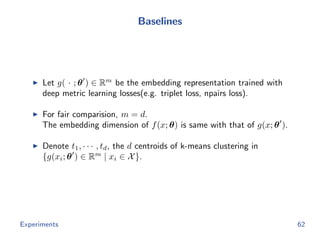

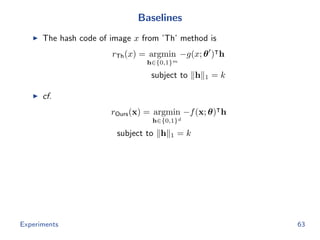

![Baselines

The hash code of image x from ’Th’ method is

rTh(x) = argmin

h∈{0,1}m

−g(x; θ ) h

subject to h 1 = k

cf.

rOurs(x) = argmin

h∈{0,1}d

−f(x; θ) h

subject to h 1 = k

The hash code of image x from ’VQ’ method is

rVQ(x) = argmin

h∈{0,1}d

[ g(x; θ ) − t1 2, · · · , g(x; θ ) − td 2]h

subject to h 1 = k

Experiments 63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-180928092811/85/Efficient-end-to-end-learning-for-quantizable-representations-75-320.jpg)