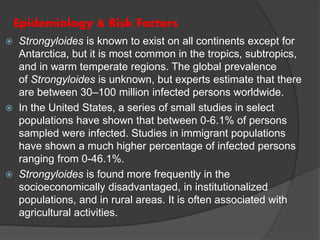

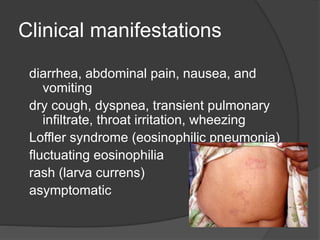

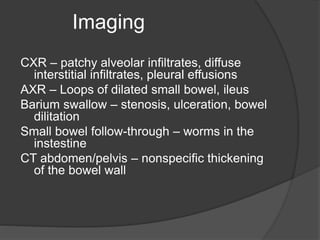

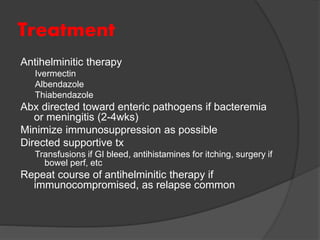

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the Strongyloides nematodes, primarily affecting individuals in tropical and subtropical regions, with significant infection rates among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Most infected individuals are asymptomatic, but severe cases can arise, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Diagnosis typically involves microscopic examination of stool samples, and treatment is crucial for all infected persons to prevent hyperinfection and other complications.