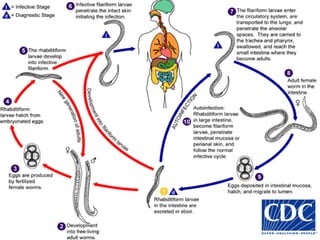

Strongyloides is a parasitic roundworm infection that was first described in French troops in Vietnam in the late 19th century. It is most common in tropical areas. Most infections are asymptomatic, but some can become severe or critical if left untreated. The parasite enters the body through exposed skin and has a complex life cycle involving an internal autoinfection that can cause chronic or disseminated infections in immunosuppressed individuals. Diagnosis is usually by microscopic identification of larvae in stool samples. Treatment is recommended for all infected individuals due to risk of severe disease.