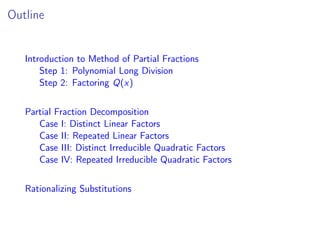

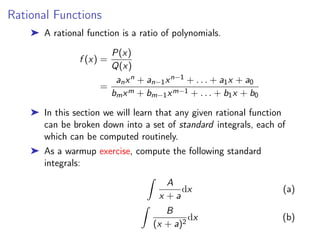

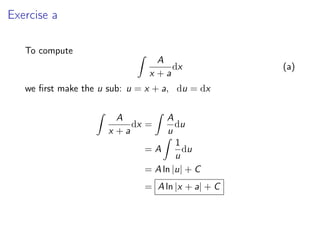

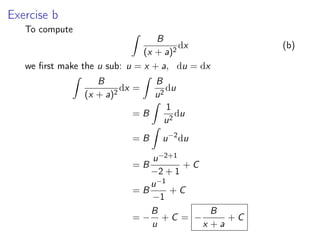

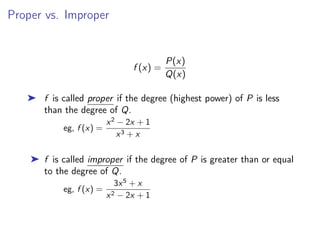

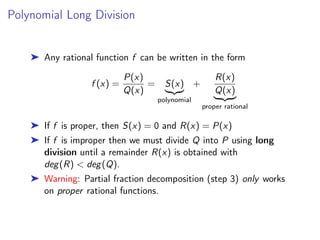

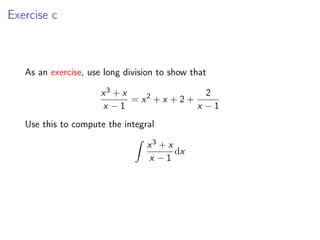

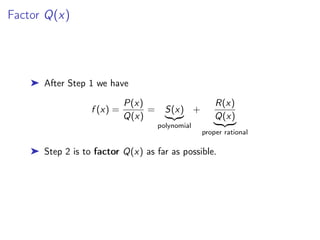

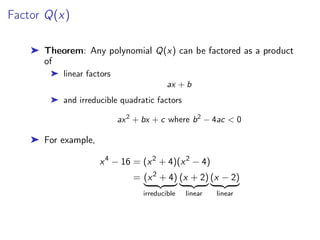

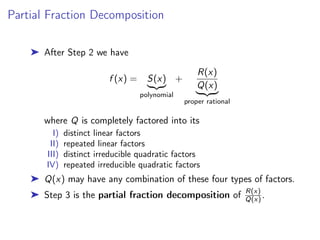

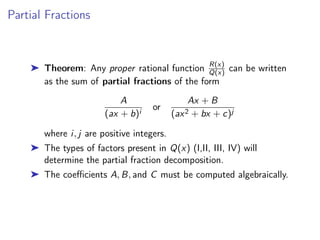

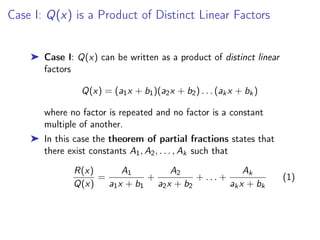

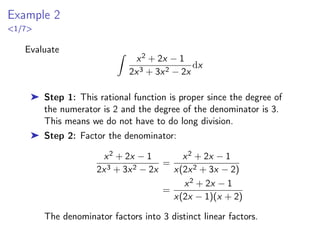

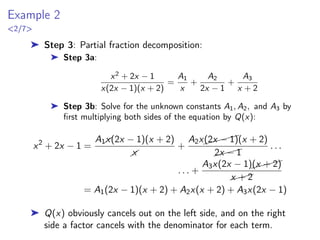

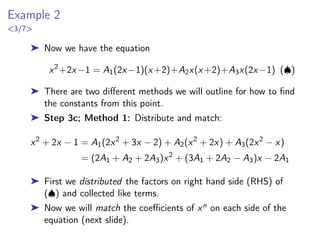

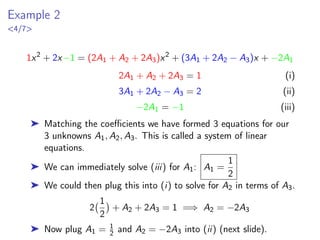

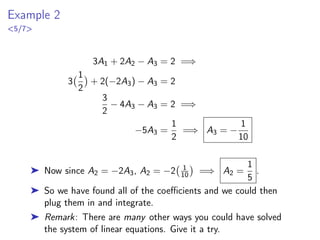

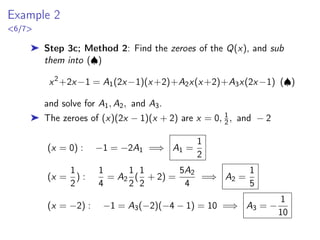

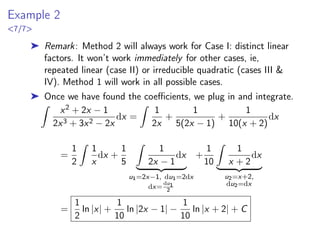

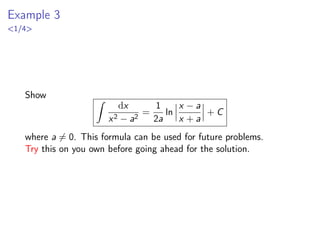

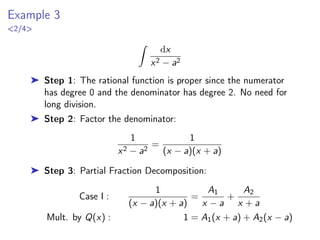

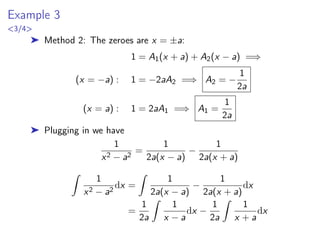

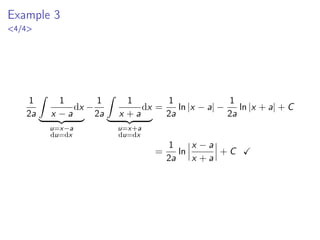

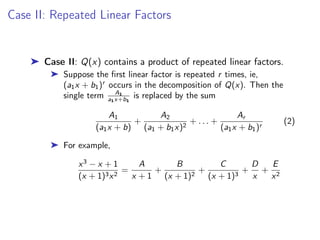

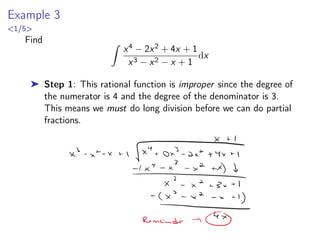

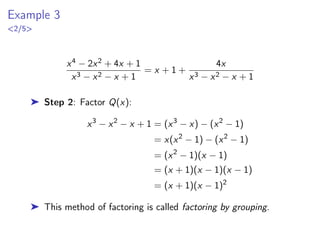

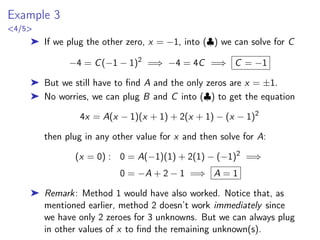

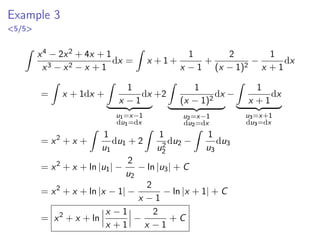

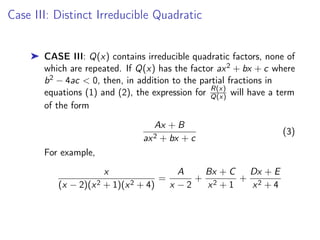

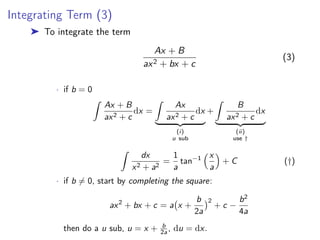

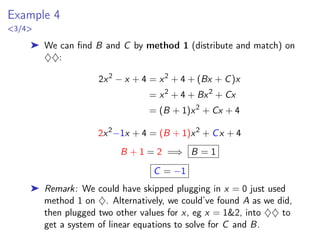

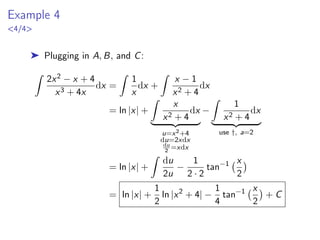

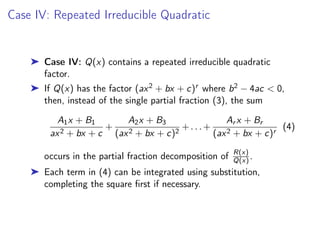

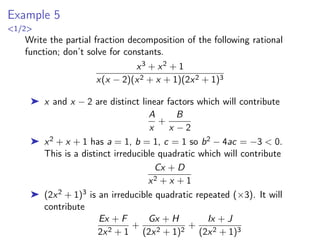

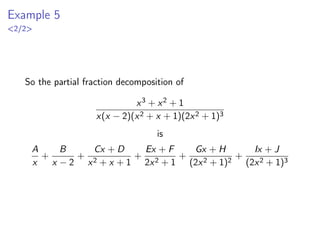

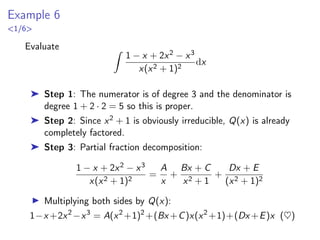

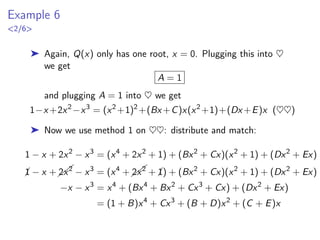

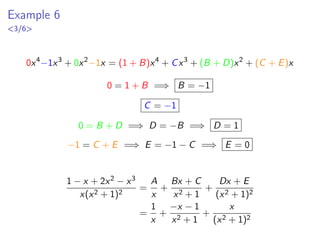

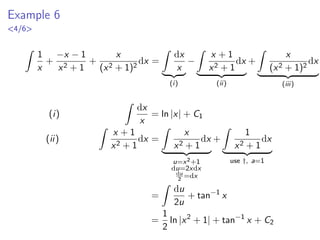

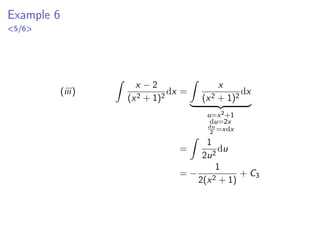

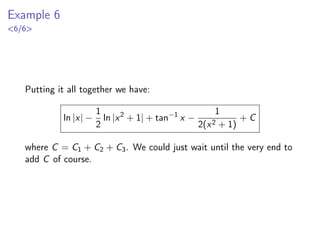

This document discusses the method of partial fractions for integrating rational functions. It begins by introducing rational functions and the goal of breaking them into standard integrals. There are four cases for partial fraction decomposition based on the factors of the denominator: I) distinct linear factors, II) repeated linear factors, III) distinct irreducible quadratic factors, and IV) repeated irreducible quadratic factors. The method involves three steps: 1) polynomial long division, 2) factoring the denominator, and 3) determining the partial fraction decomposition. Examples are provided to demonstrate the technique.