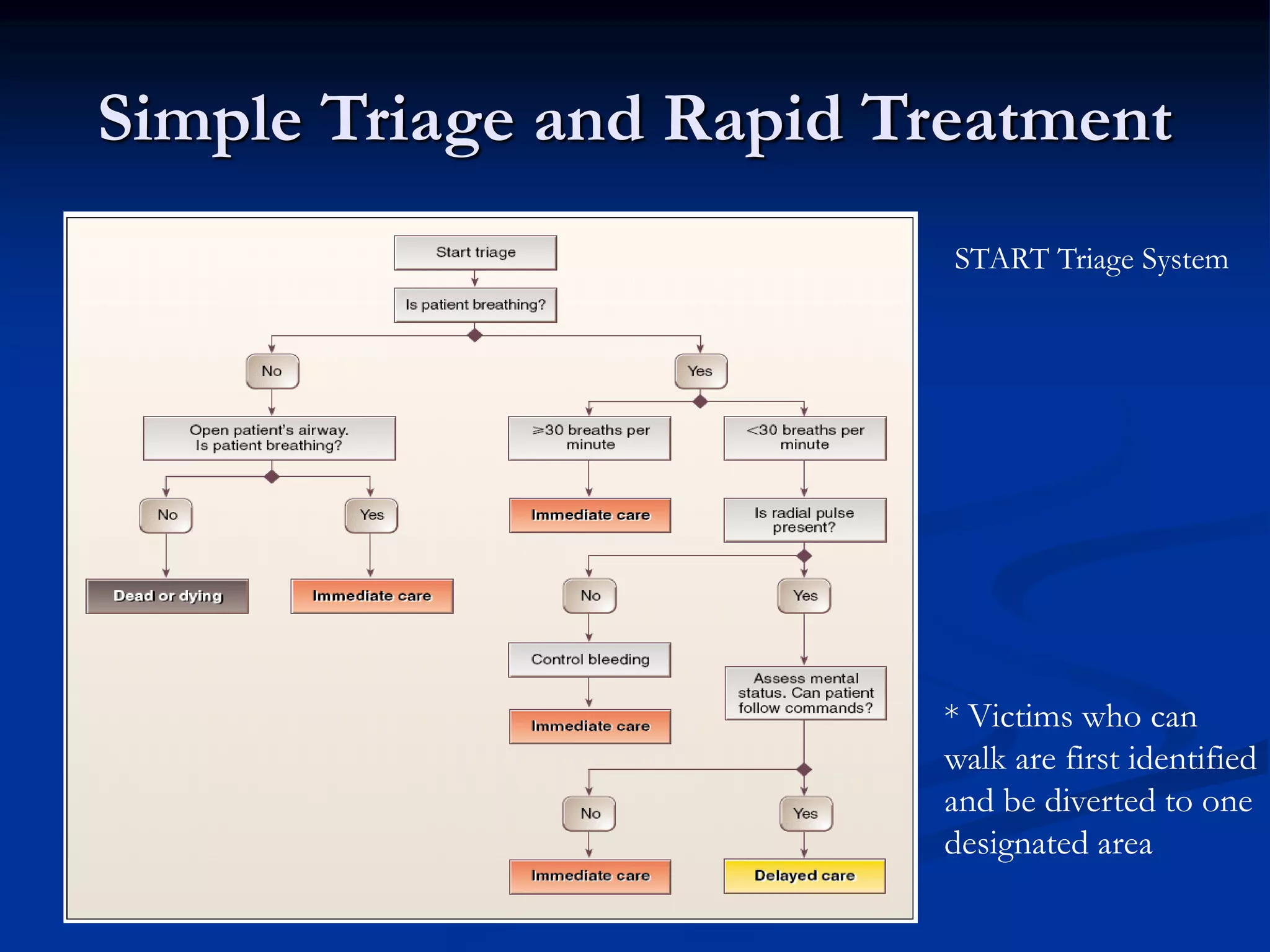

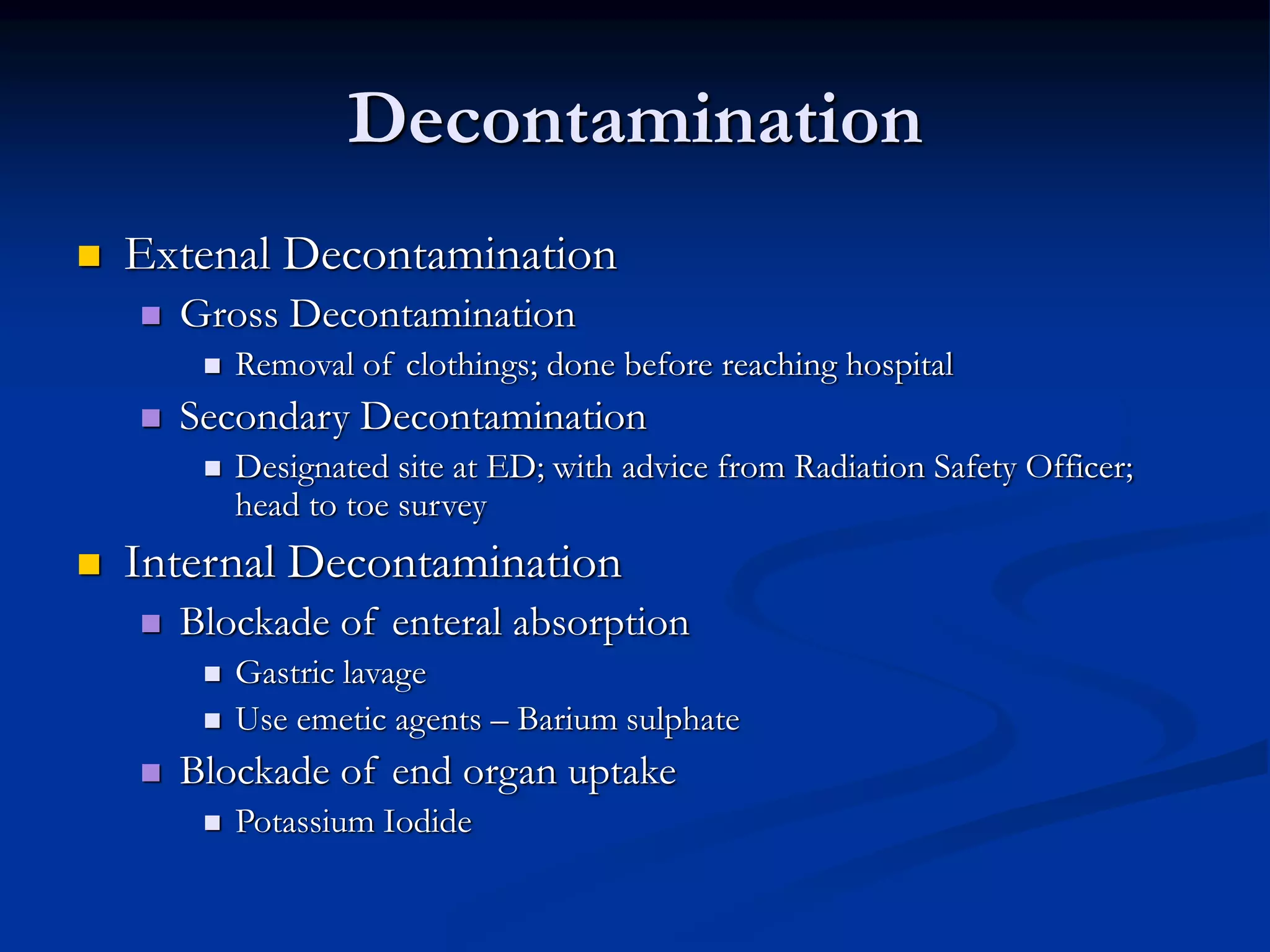

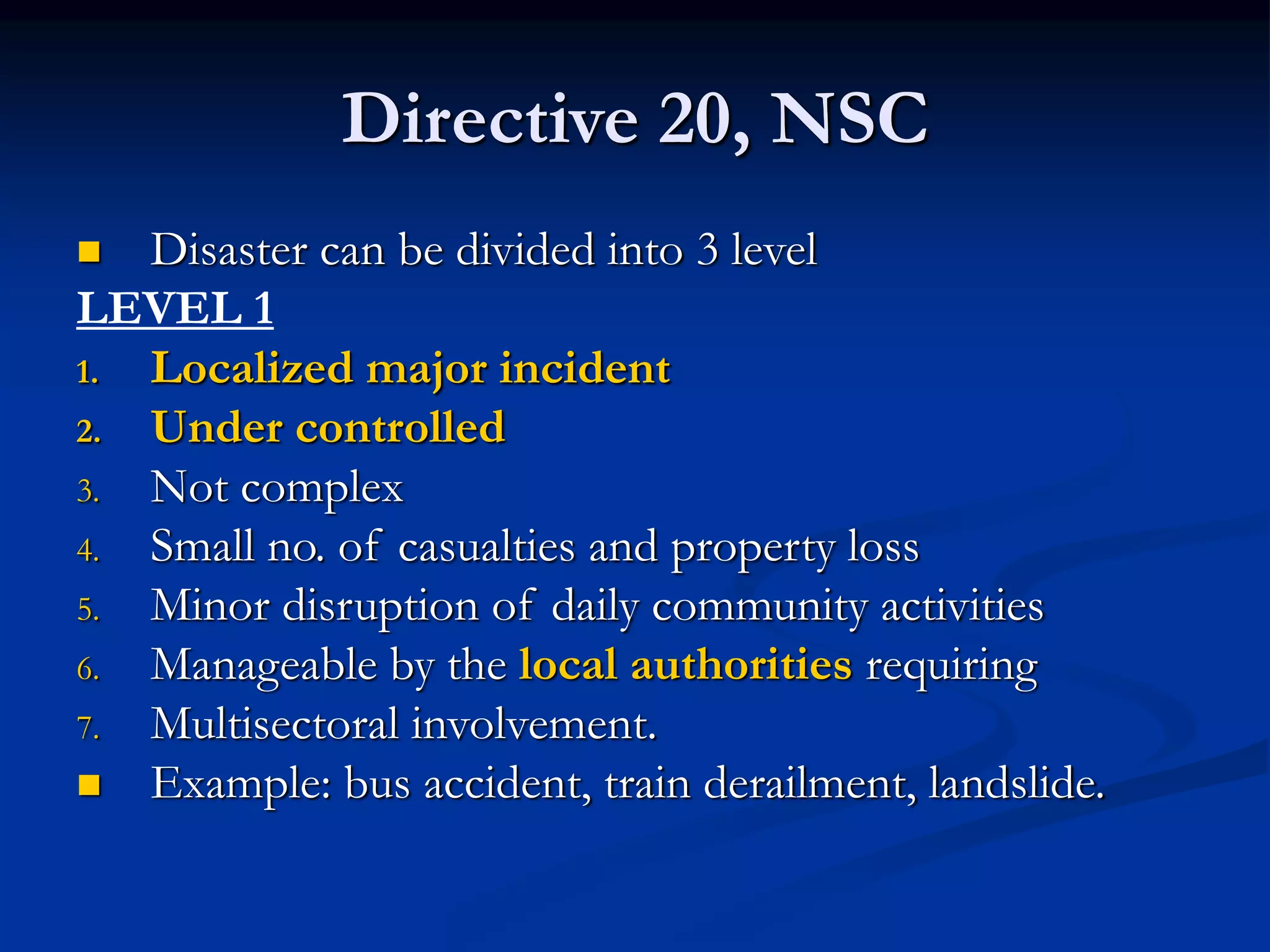

This document discusses the role of emergency physicians in responding to CBRNE (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive) attacks. It begins by defining key terms like disaster, mass casualty incidents, and terrorism. It then reviews lessons learned from past terrorist attacks involving weapons of mass destruction. Early detection of biological attacks can be aided by syndromic surveillance of emergency department visits. The document outlines recommended preparedness criteria for emergency departments. Finally, it describes the "seven Ds" that define an emergency physician's role in disaster response: detection, declaration, defense, decontamination, delegation, drugs, and disposition.

![Key Criteria Defining a Terrorist

Attack

Violence

"the only general characteristic [of terrorism] generally agreed

upon is that terrorism involves violence and the threat of

violence"

-Walter Laqueur of the Center for Strategic and International Studies

Psychological Impact and Fear

attack was carried out in such a way as to maximize the

severity and length of the psychological impact.

Perpetrated for a Political Goal

This is often the key difference between an act of terrorism

and a hate crime or lone-wolf "madman" attack

The political change is desired so badly that failure is seen as

a worse outcome than the deaths of civilians.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crbne2-160304083803/75/Role-of-Emergency-Physicians-During-CBRNE-Attack-The-Malaysian-Context-17-2048.jpg)