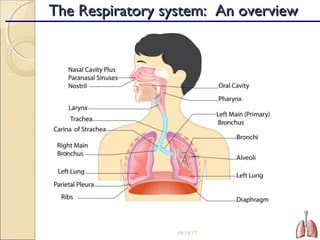

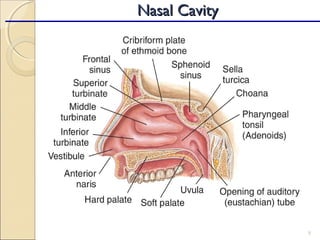

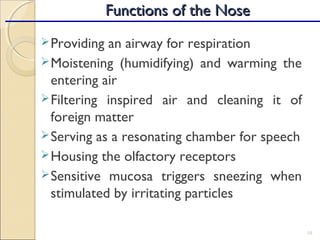

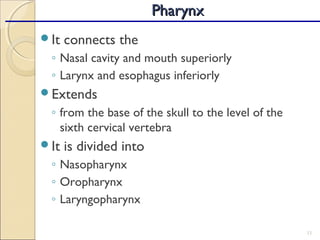

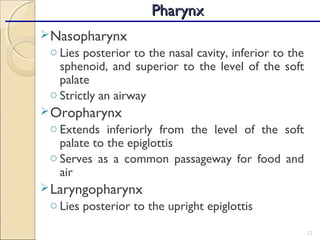

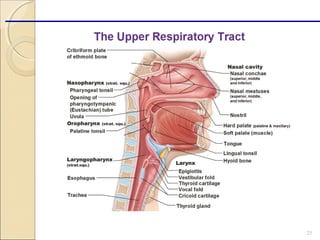

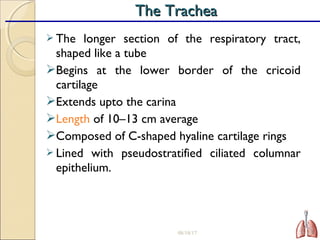

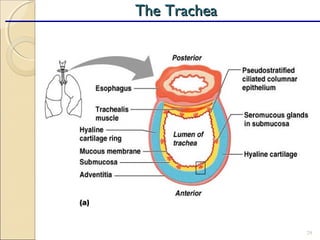

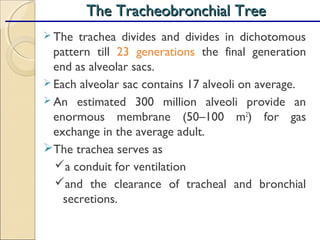

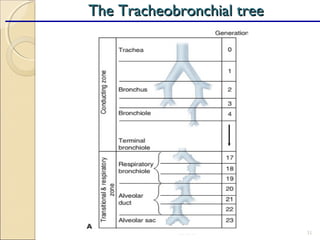

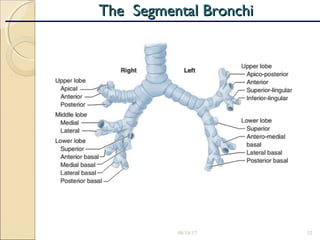

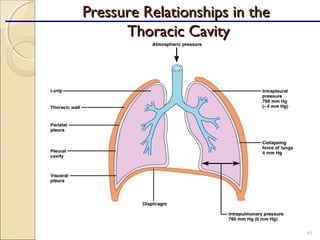

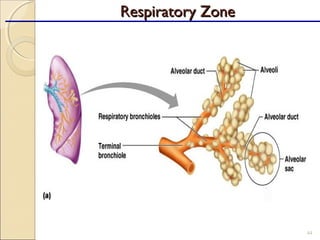

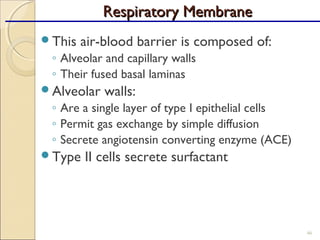

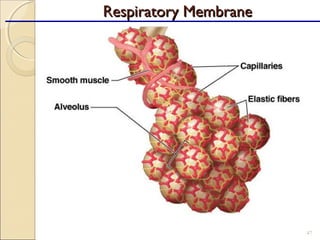

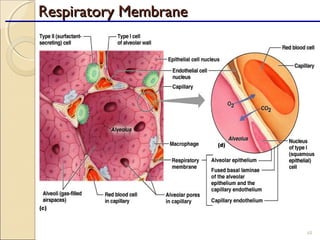

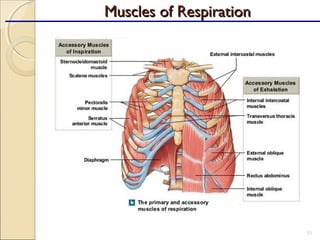

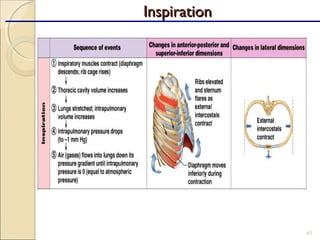

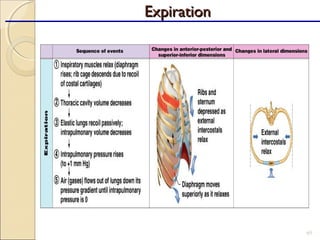

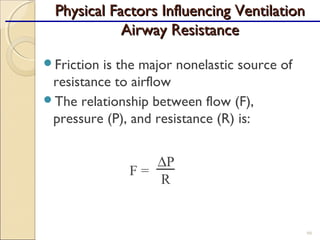

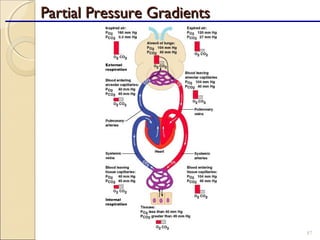

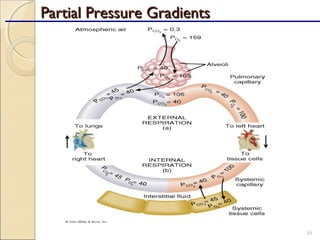

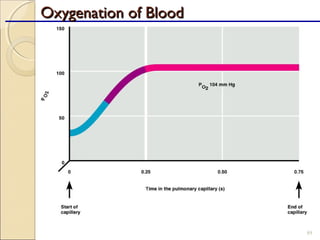

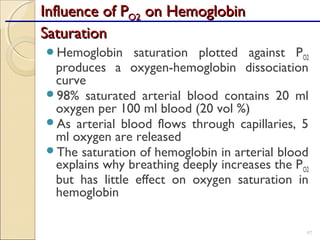

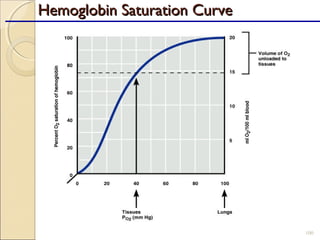

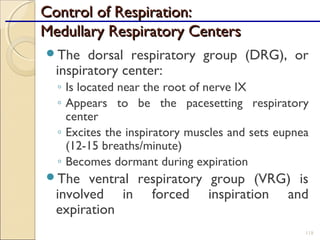

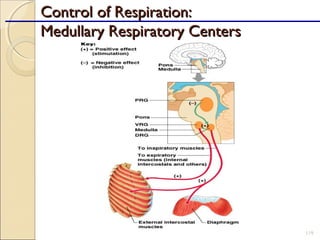

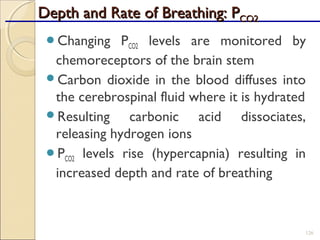

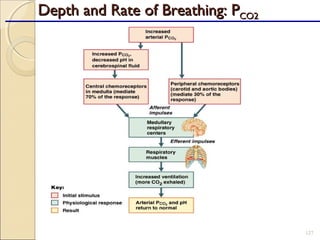

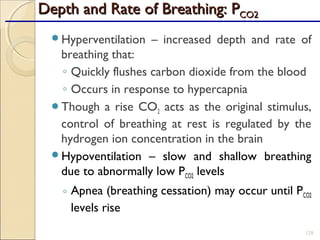

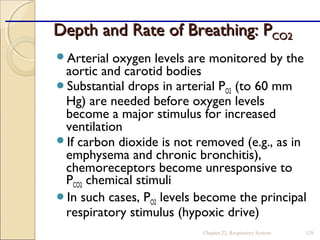

The document provides a detailed overview of the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, emphasizing the importance of the brain's need for oxygen and the roles of various respiratory structures. It covers the respiratory tract's divisions, mechanisms of gas exchange, and the functions of respiratory muscles involved in ventilation. Additionally, it discusses the blood supply to the lungs and the mechanics of breathing, including pressure relationships and factors influencing ventilation.