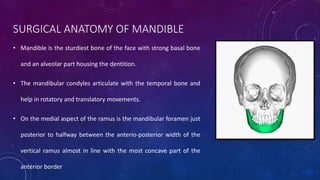

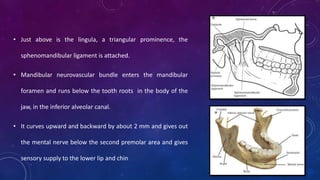

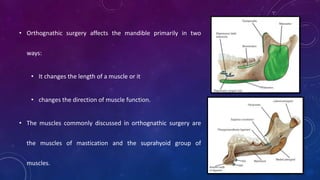

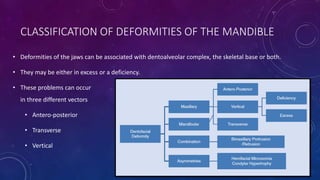

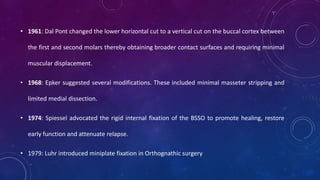

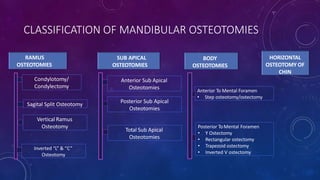

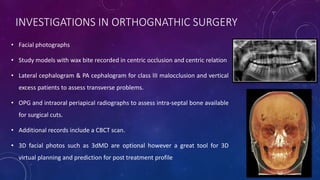

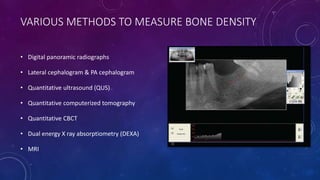

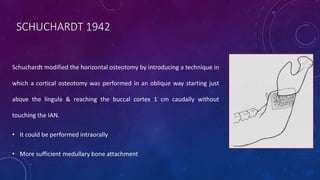

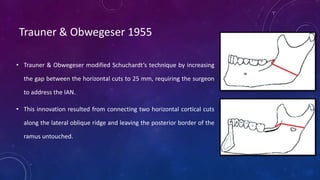

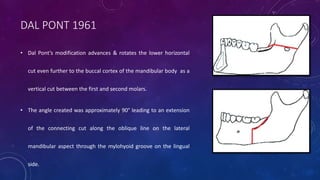

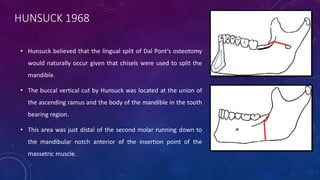

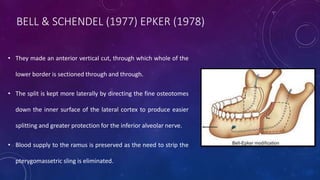

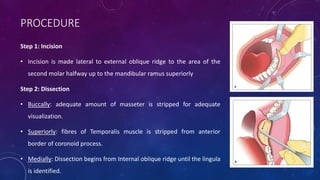

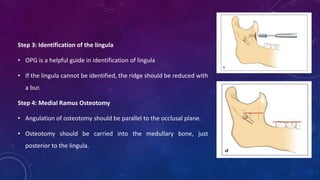

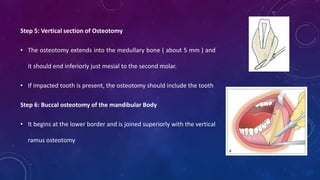

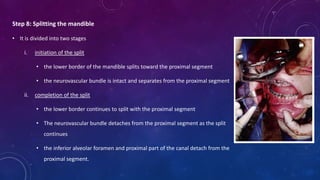

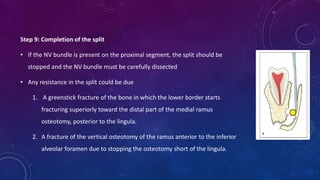

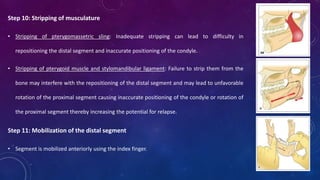

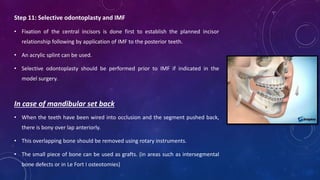

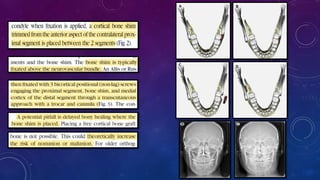

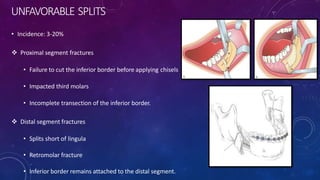

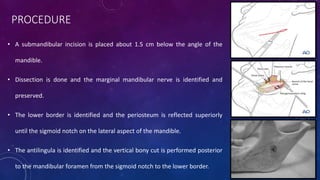

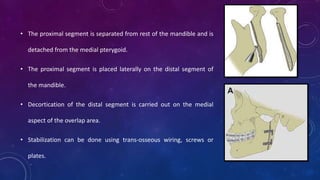

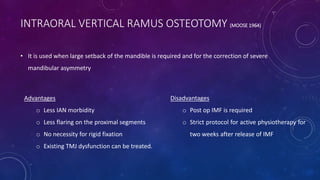

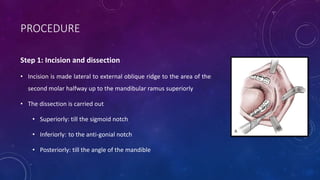

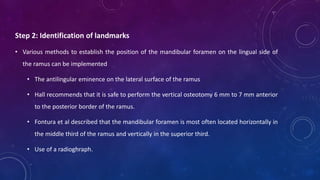

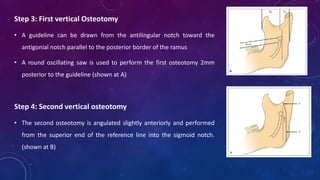

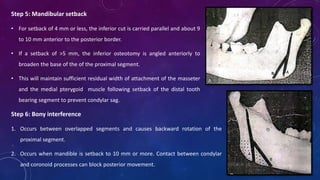

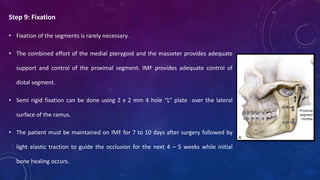

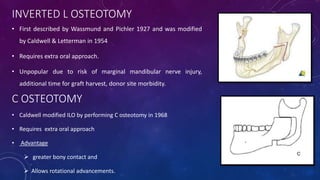

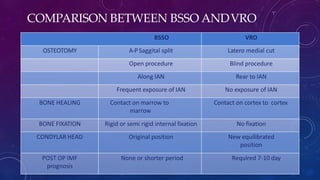

This document provides information on the Ramus osteotomy procedure, specifically the sagittal split osteotomy (SSO). It discusses the history and evolution of the SSO technique from its early developments to modern procedures. Key steps of the current SSO procedure are outlined, including incision, dissection, identification of anatomical landmarks, and performing the osteotomies along the medial ramus, vertical body, and buccal cortex before splitting the mandible. The SSO allows correction of mandibular deformities by repositioning the proximal and distal segments.