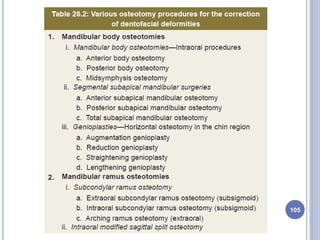

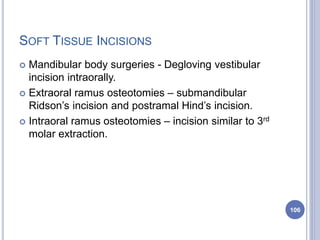

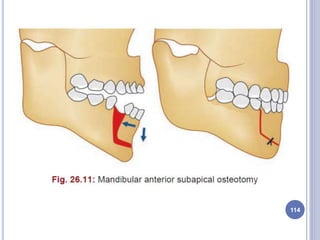

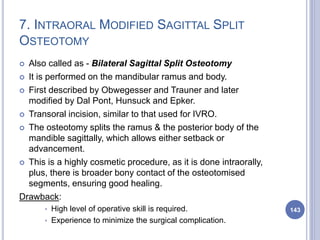

The document provides information about mandibular orthognathic surgeries, including:

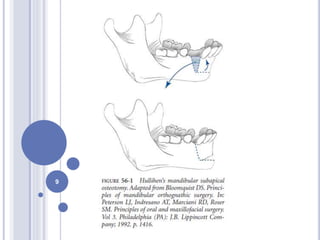

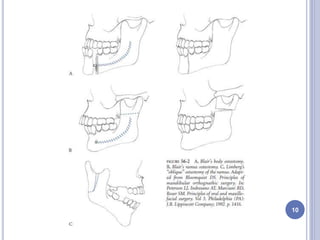

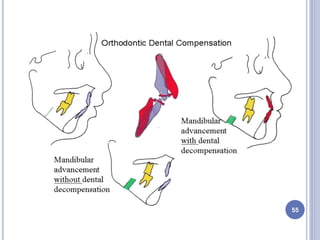

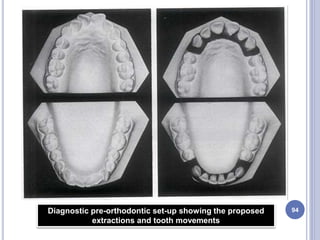

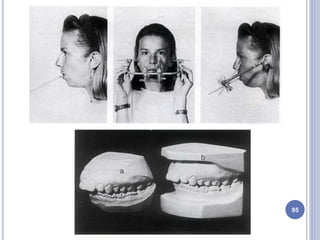

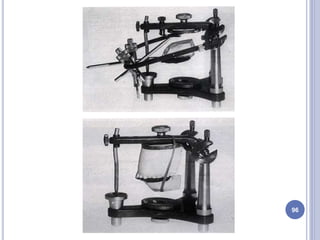

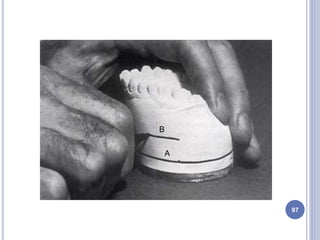

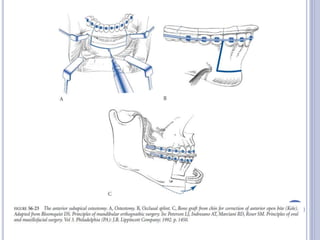

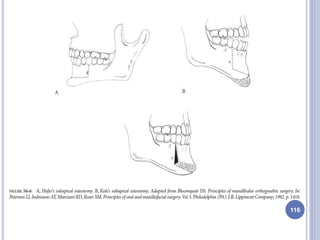

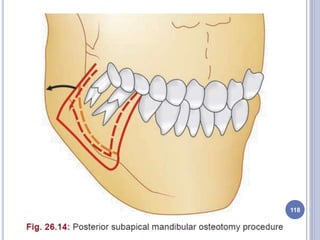

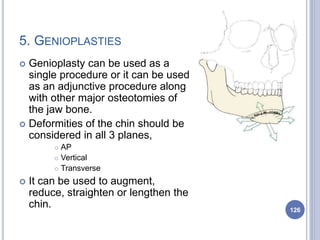

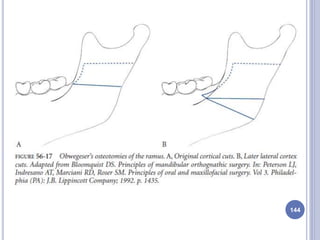

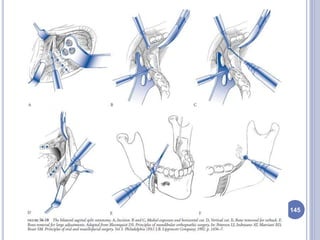

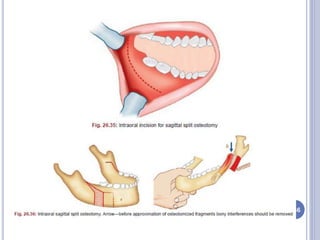

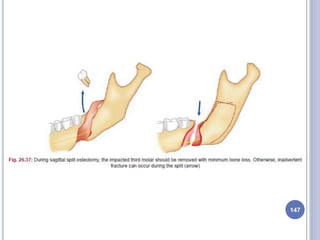

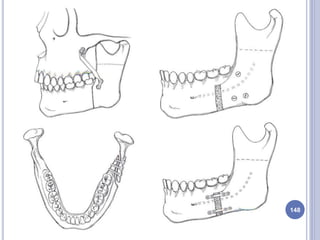

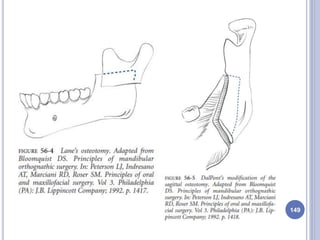

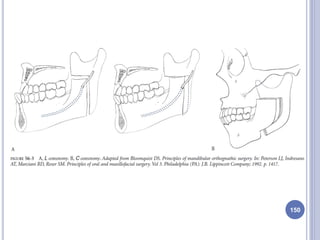

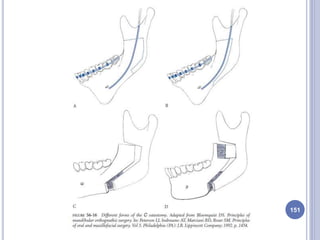

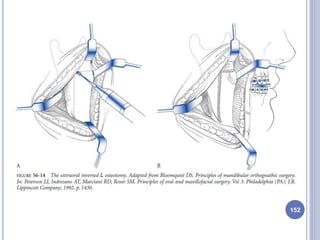

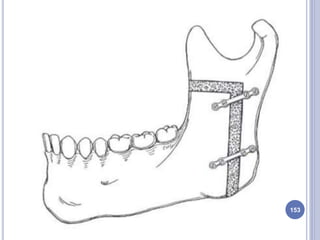

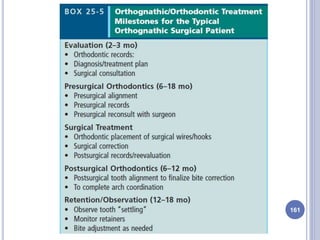

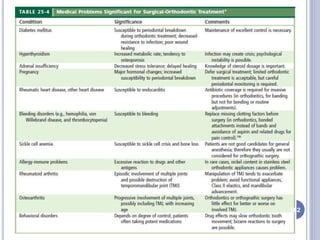

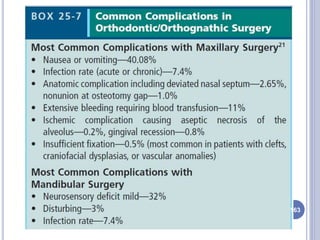

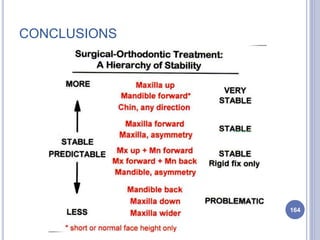

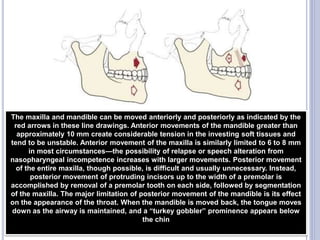

- Orthognathic surgery involves correcting dentofacial deformities with orthodontics combined with surgical modification of facial structures.

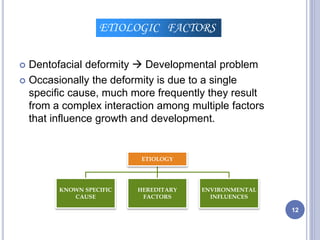

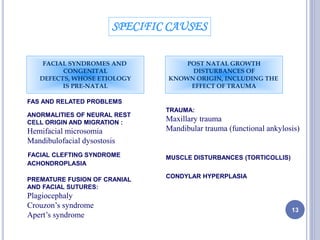

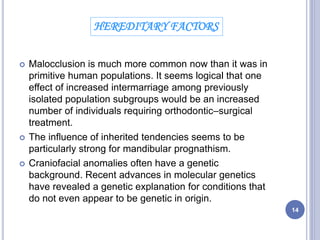

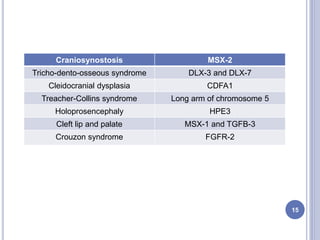

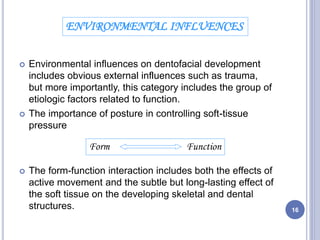

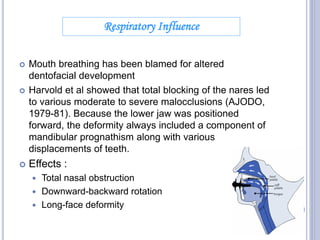

- Factors influencing facial development include heredity, environment, trauma, and functional influences.

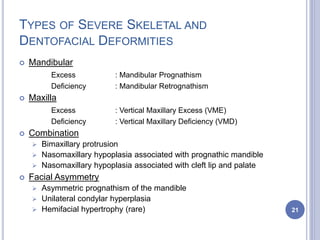

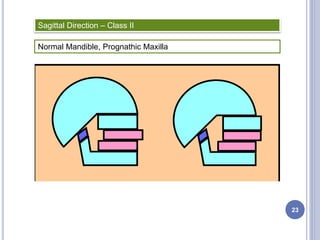

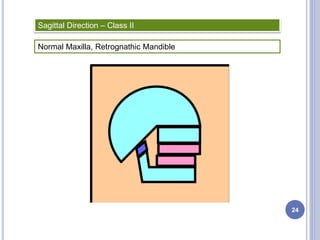

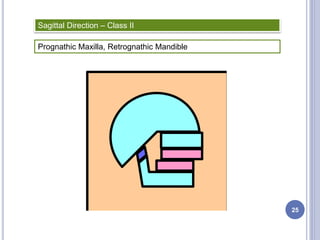

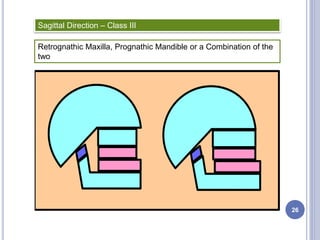

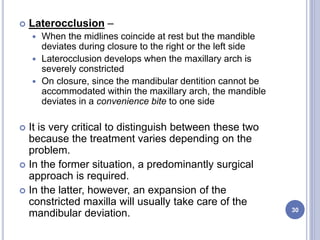

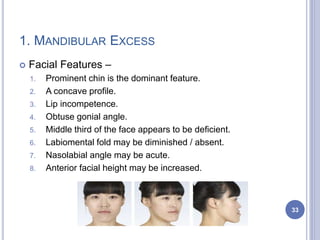

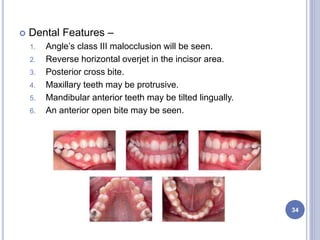

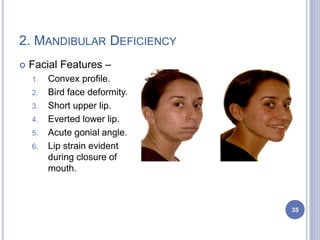

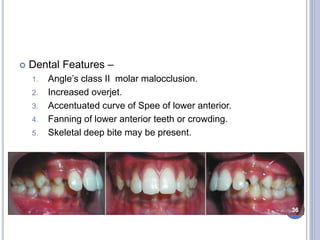

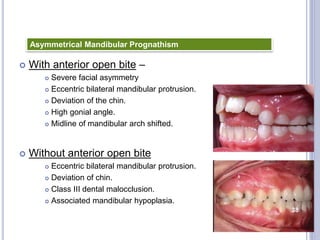

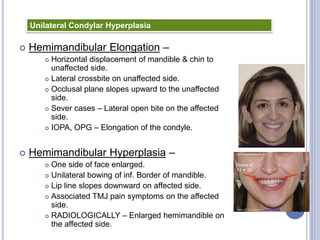

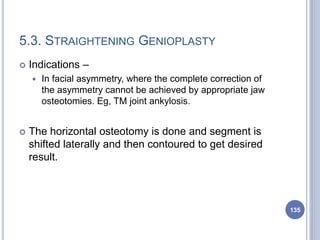

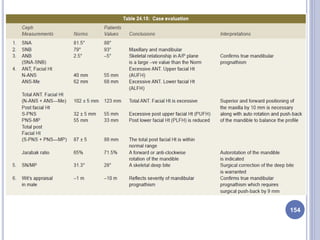

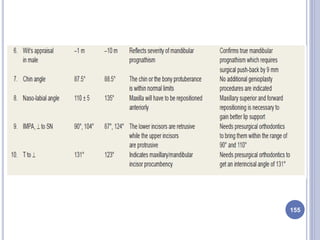

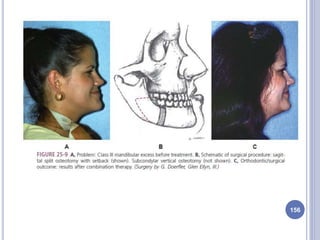

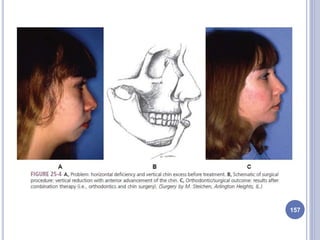

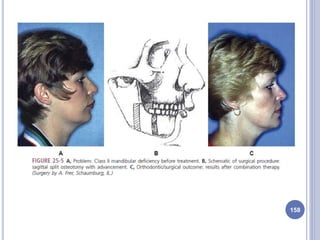

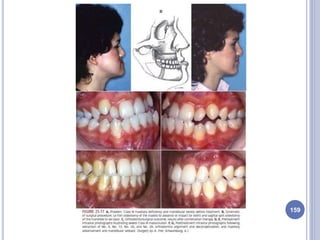

- Common dentofacial deformities include mandibular excess/deficiency, maxillary excess/deficiency, and facial asymmetry.

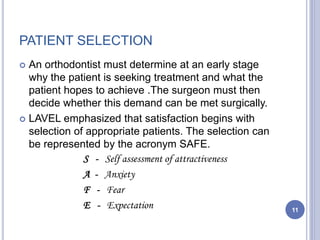

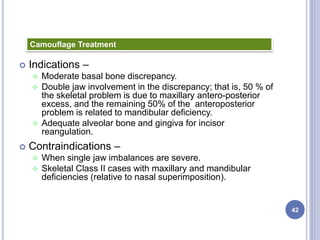

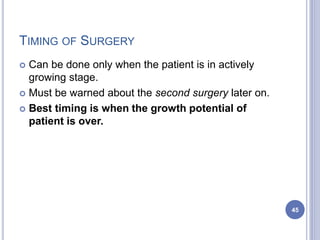

- Treatment options include growth modification, camouflage treatment, and orthognathic surgery. Orthognathic surgery aims to achieve optimal function, aesthetics, and stability.