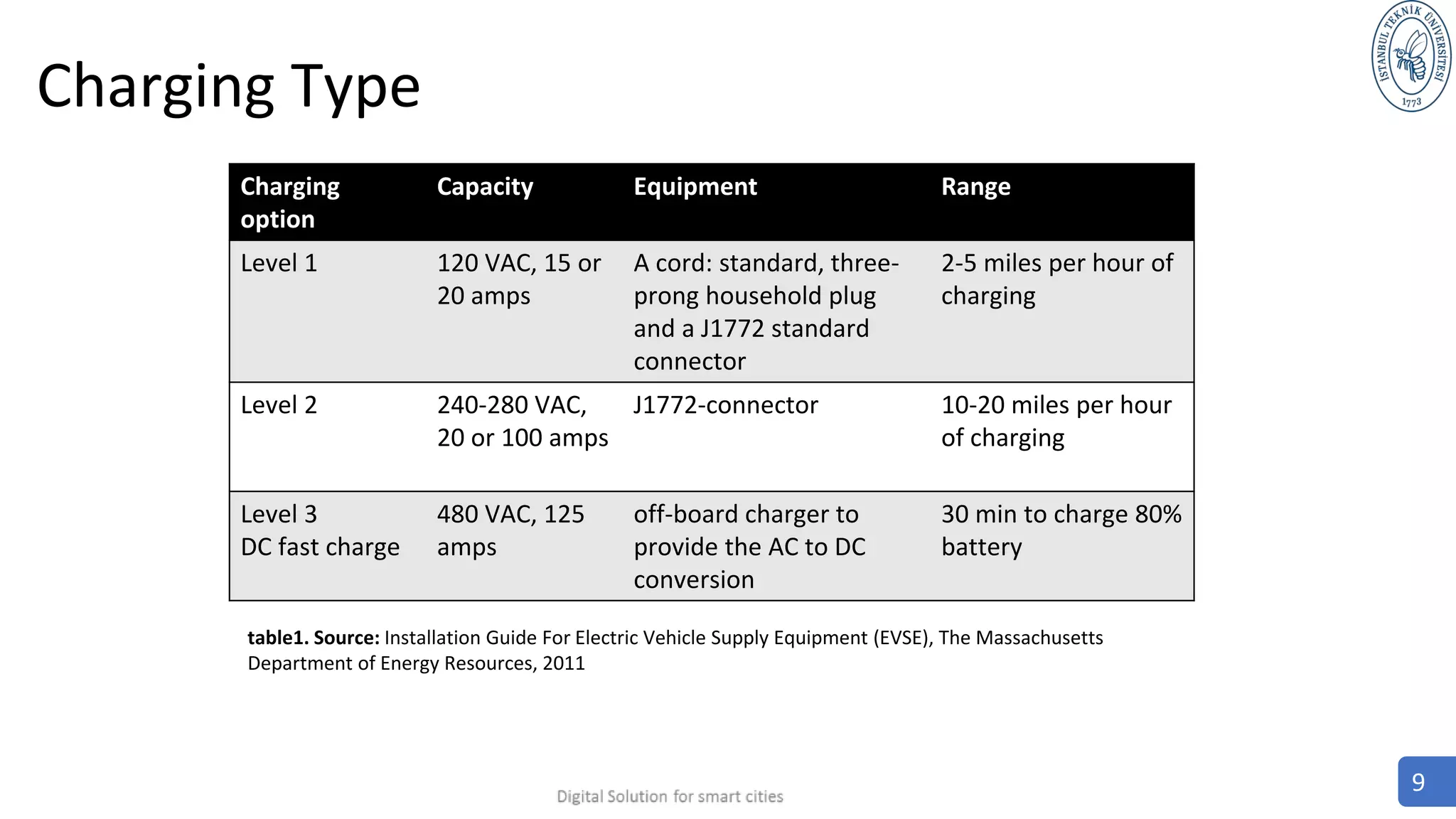

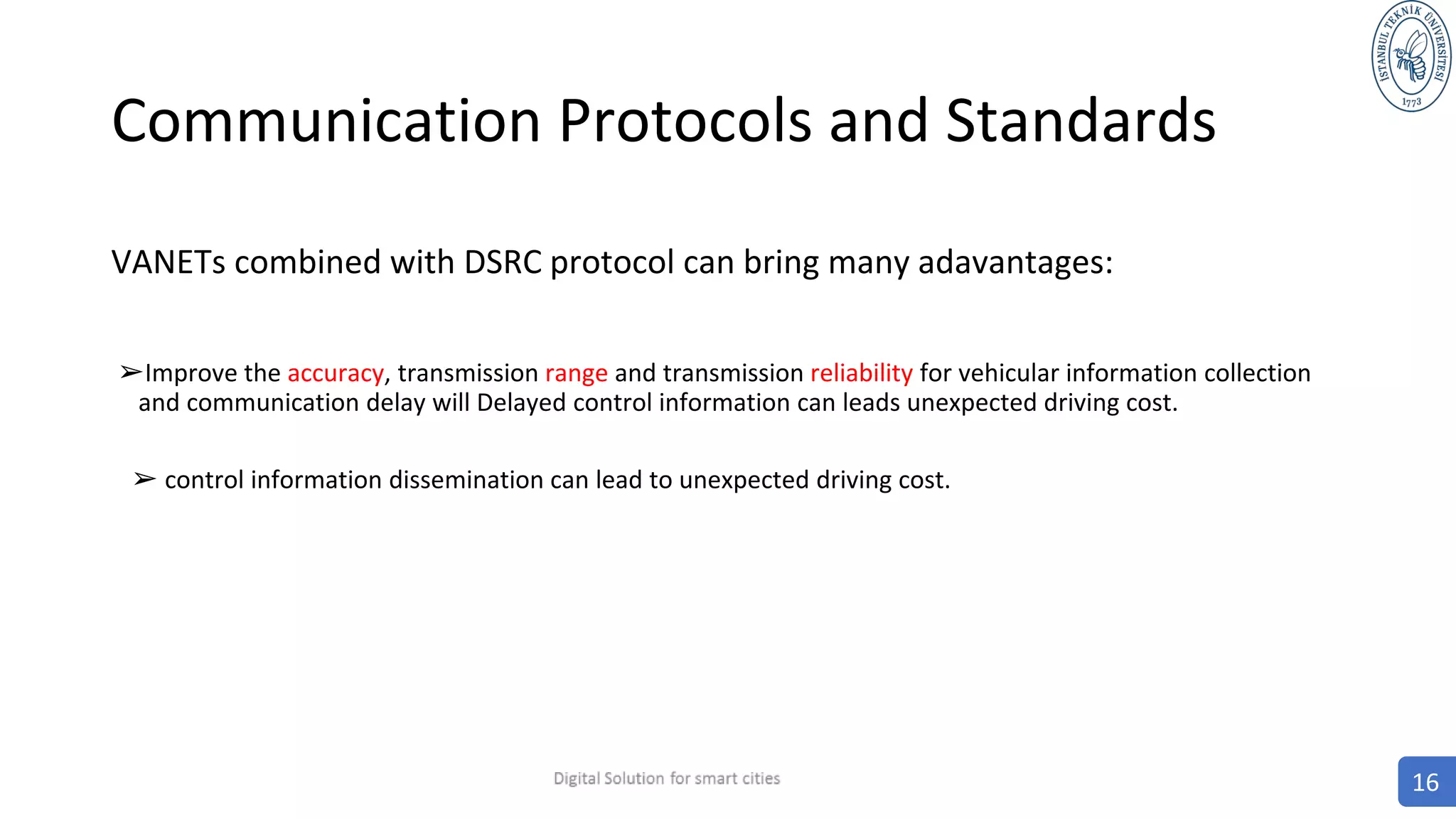

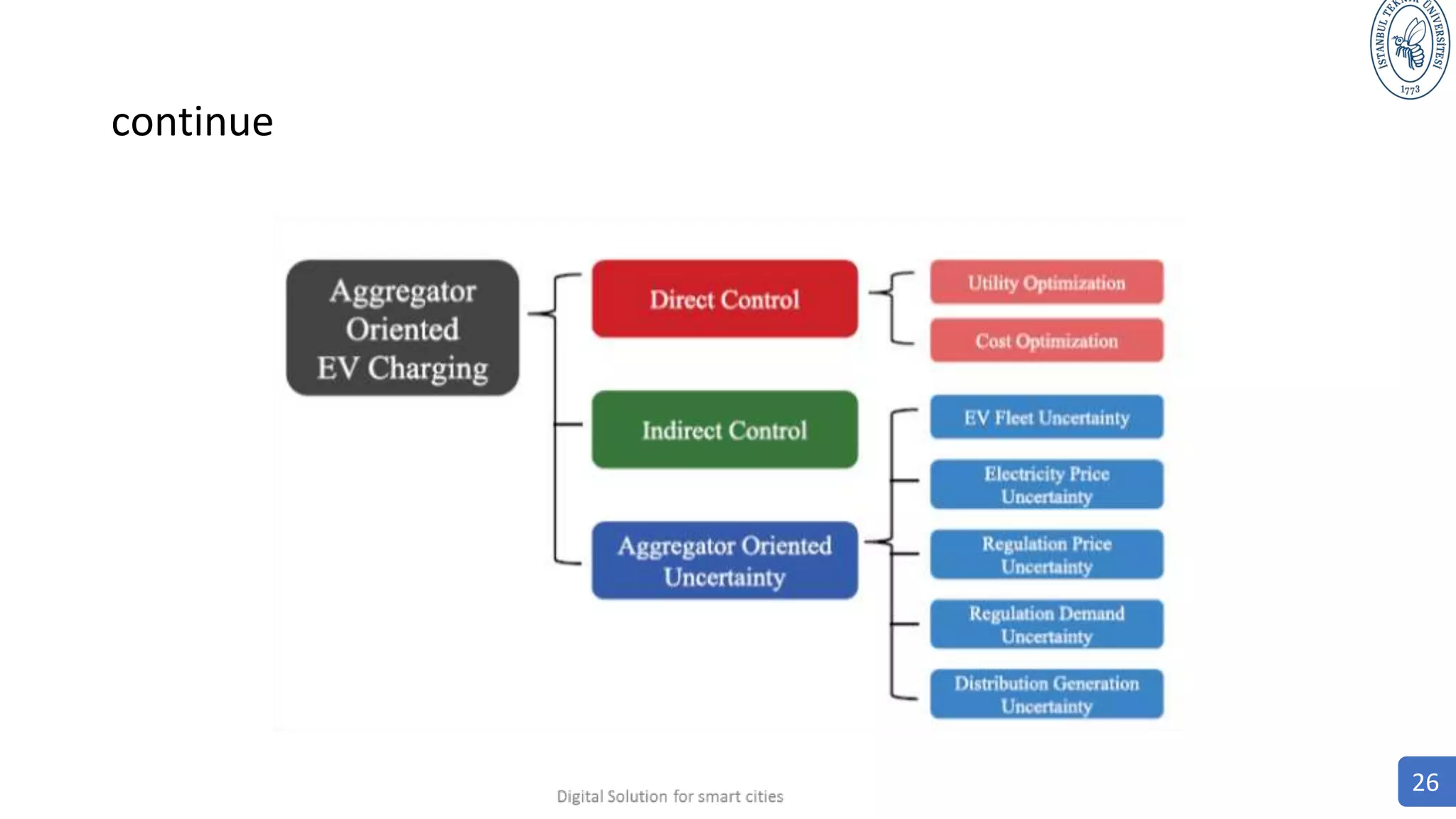

This document summarizes a survey paper on smart charging for electric vehicles from an algorithmic perspective. It discusses smart grid-oriented EV charging approaches like load flattening, frequency regulation, and voltage regulation. It also discusses aggregator-oriented and customer-oriented EV charging approaches and the uncertainties involved. Future work opportunities are identified in areas like battery modeling, routing, and communication requirements to further the smart interaction between electric vehicles and the smart grid.

![References

[1] C. Chan, “The state of the art of electric, hybrid, and fuel cell vehicles,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 95, no. 4, pp. 704–718, Apr. 2007.

[2] A. Emadi, Y. J. Lee, and K. Rajashekara, “Power electronics and motor drives in electric, hybrid electric, and plug-in hybrid

electric vehicles,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 2237–2245, Jun. 2008.

[3] N. Tanaka et al., “Technology roadmap: Electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles,” International Energy Agency, Paris,

France, Tech. Rep., 2011 [Online]. Available:

http:www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/EVPHEV_Roadmap.pdf

[4] Electric Drive Transportation Association. (2015). Electric Drive Sales,Dashboard [Online].

Available:http://electricdrive.org/index.php?ht=d/ sp/i/20952/pid/20952, accessed on Aug. 11, 2015.

[5] M. Yilmaz and P. Krein, “Review of battery charger topologies, charging power levels, and infrastructure for plug-in

electric and hybrid vehicles,”IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 2151–2169, May 2013.

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartcitypresentation-171122103849/75/presntation-about-smart-charging-for-the-vehicles-35-2048.jpg)

![References

[6] O. Ardakanian, C. Rosenberg, and S. Keshav, “Distributed control ofelectric vehicle charging,” in Proc. 4th Int. Conf. Future

Energy Syst., New York, NY, USA, 2013, pp. 101–112.

[7] X. Fang, S. Misra, G. Xue, and D. Yang, “Smart grid-the new and improved power grid: A survey,” IEEE Commun. Surveys

Tuts., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 944–980, Dec. 2012.

[8] R. C. Green, II, L. Wang, and M. Alam, “The impact of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on distribution networks: A review

and outlook,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 544–553, Jan. 2011.

[9] W. Su, H. Eichi, W. Zeng, and M.-Y. Chow, “A survey on the electrification of transportation in a smart grid environment,”

IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Feb. 2012.

[10] D. B. Richardson, “Electric vehicles and the electric grid: A review of modeling approaches, impacts, and renewable

energy integration, "Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 19, pp. 247–254, Mar. 2013.

[11] F. Mwasilu, J. J. Justo, E.-K. Kim, T. D. Do, and J.W. Jung, “Electric vehicles and smart grid interaction: A review on vehicle

to grid and renewable energy sources integration,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 34, pp. 501–516, Jun. 2014.

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartcitypresentation-171122103849/75/presntation-about-smart-charging-for-the-vehicles-36-2048.jpg)

![Reference

[12] L. James and L. John, “Electric vehicle technology explained,” 2nd ed.,West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2003.

[13] D. Tuttle and R. Baldick, “The evolution of plug-in electric vehicle-grid interactions,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 3, no. 1,

pp. 500–505, Mar. 2012.

[14] A. McCrone, “Electric vehicle battery prices down 14% year on year,” Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2012 [Online].

Available:https://www.newenergyfinance.com/PressReleases/view/210, accessedAug. 11, 2015.

[15] T. Markel, “Plug-in electric vehicle infrastructure: A foundation forelectrified transportation,” presented at the MIT

Energy InitiativeTransp. Electrif. Symp., Cambridge, MA, 2010.

[16] L. Dickerman and J. Harrison, “A new car, a new grid,” IEEE PowerEnergy Mag., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 55–61, Mar. 2010.

[17] T.-K. Lee, Z. Bareket, T. Gordon, and Z. Filipi, “Stochastic modeling forstudies of real-world phev usage: Driving schedule

and daily temporal

distributions,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 1493–1502,May 2012.

[18] S. Vagropoulos and A. Bakirtzis, “Optimal bidding strategy for electric

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartcitypresentation-171122103849/75/presntation-about-smart-charging-for-the-vehicles-37-2048.jpg)