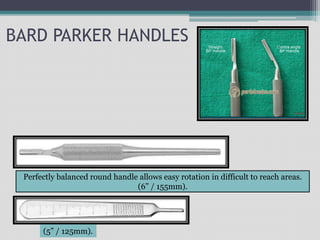

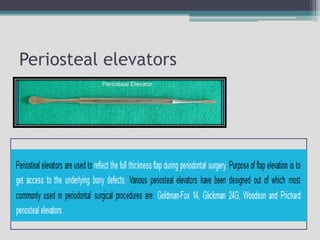

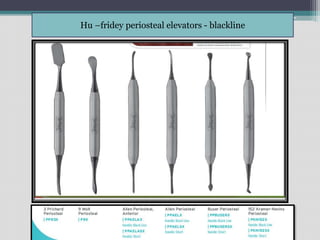

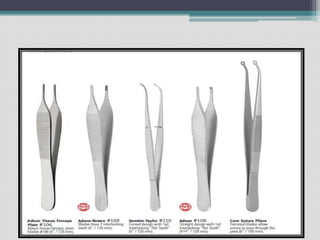

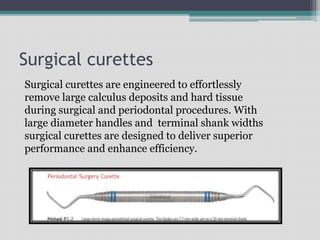

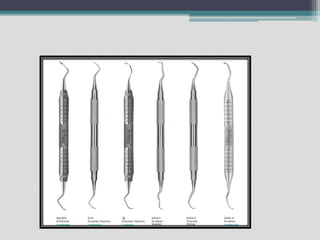

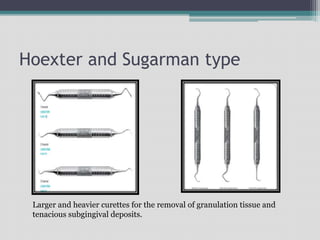

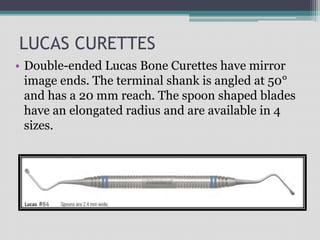

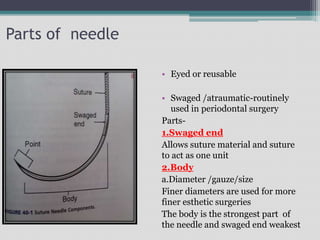

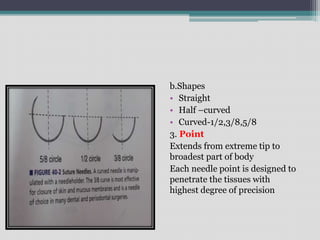

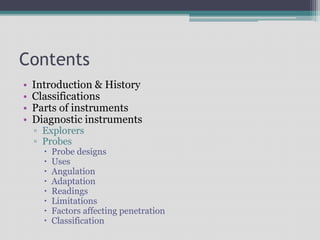

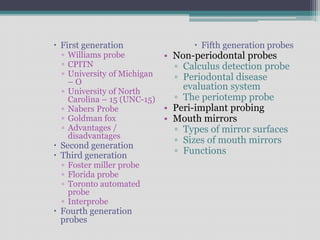

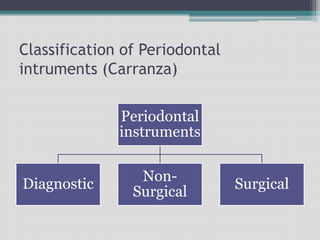

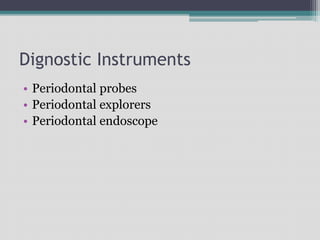

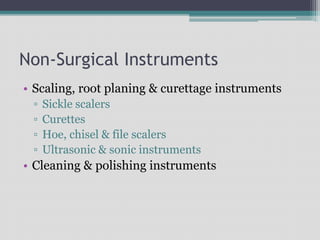

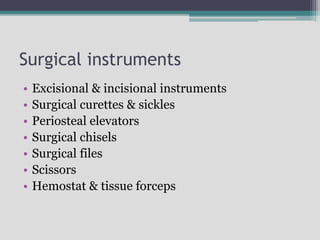

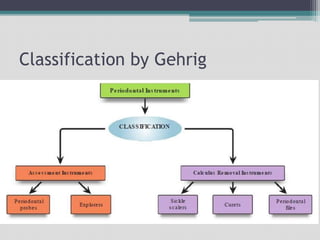

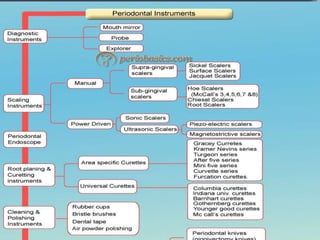

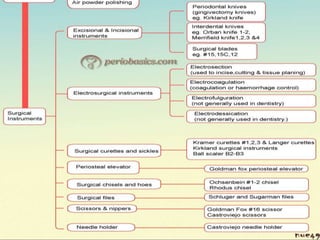

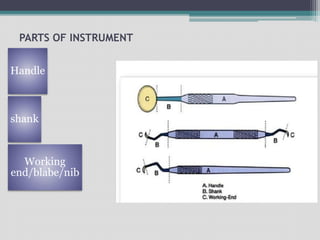

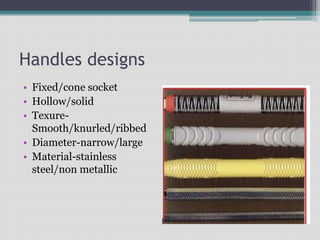

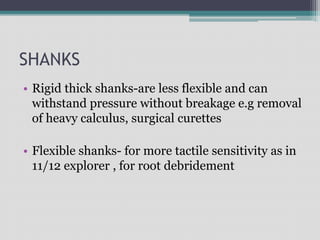

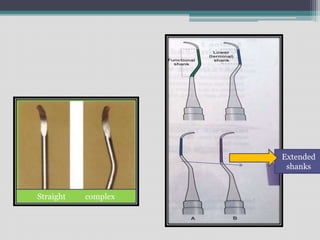

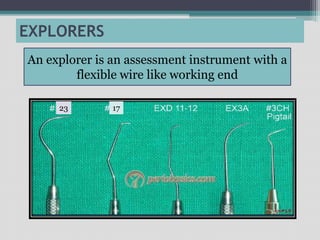

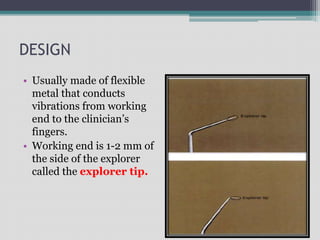

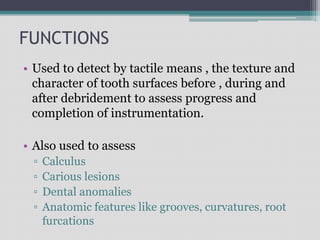

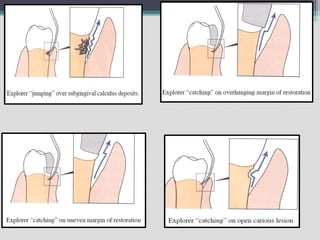

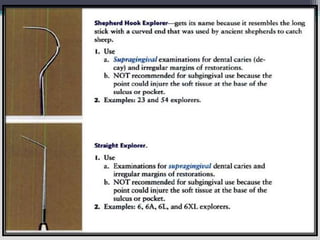

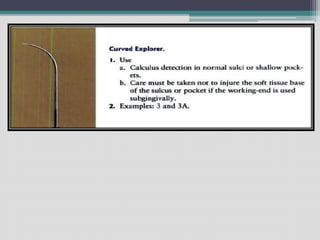

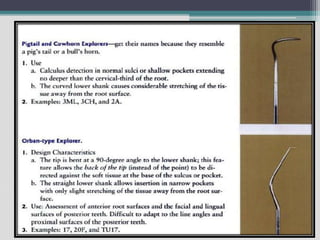

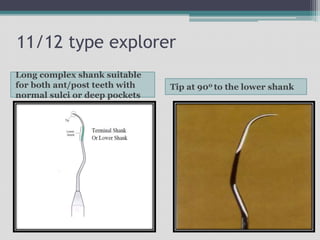

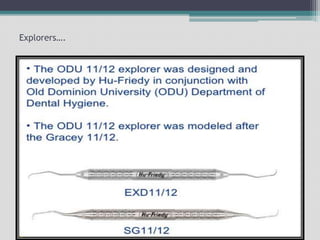

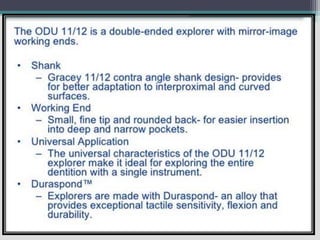

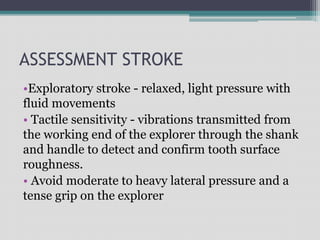

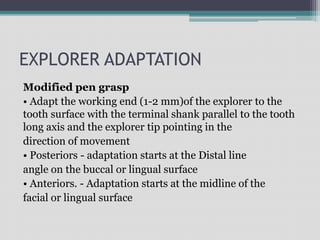

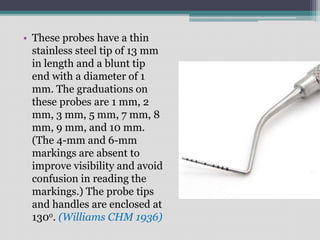

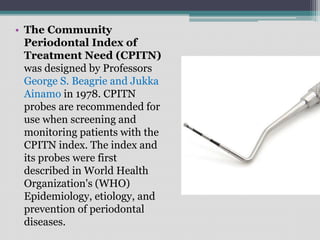

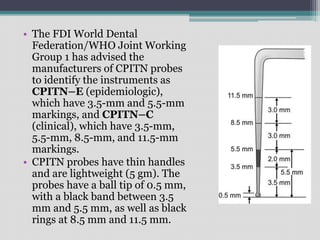

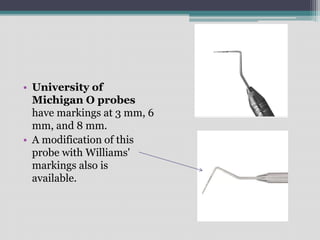

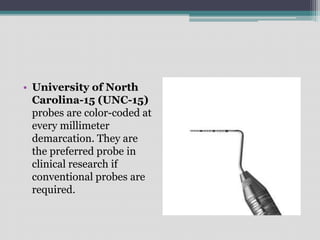

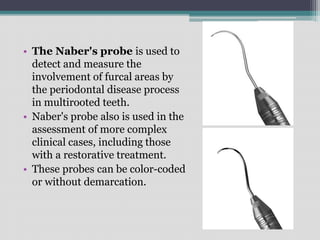

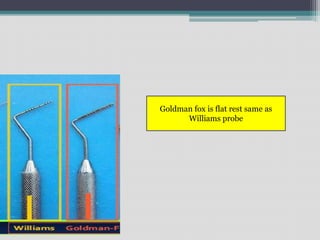

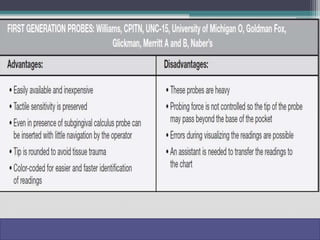

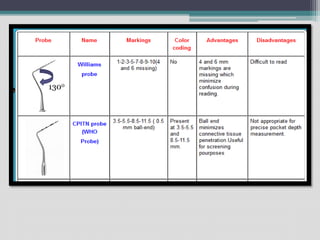

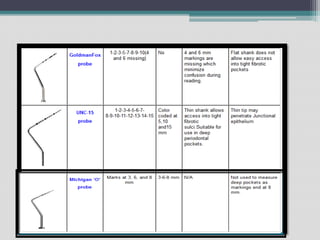

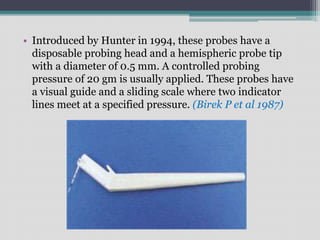

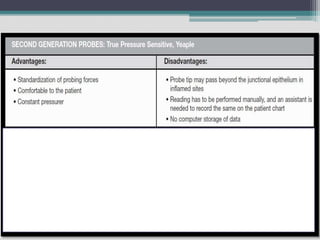

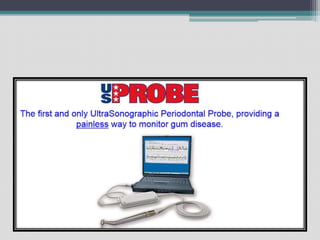

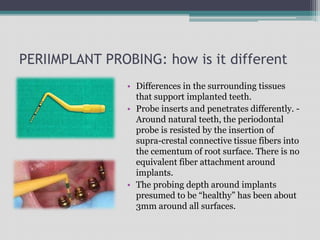

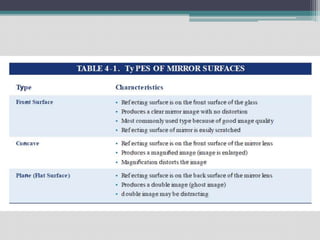

This document discusses the history and classification of periodontal instruments used for diagnosis and surgery. It describes the various types of diagnostic instruments including probes and explorers used to measure and assess periodontal pockets and disease. Surgical instruments like scalpels, curettes, and forceps used to treat periodontal disease are also outlined. The document categorizes instruments based on design and generations from first to fifth generation probes, with newer generations incorporating improvements like standardized probing pressure and automated data collection.

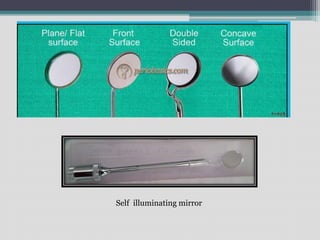

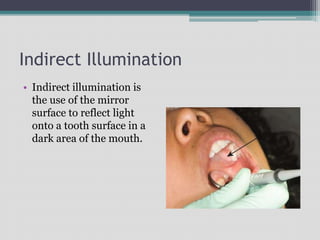

![Transillumination

• Transillumination is the

technique of directing

light off of the mirror

surface and through the

anterior teeth. [Trans =

through + Illumination =

lighting up].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/periodontalinstruments-210522140026/85/Periodontal-instruments-107-320.jpg)