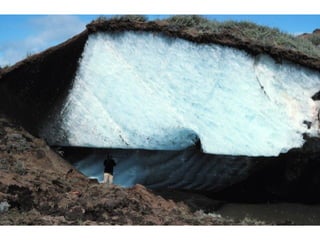

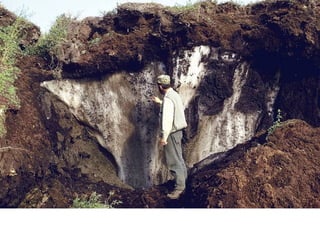

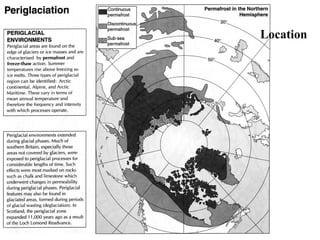

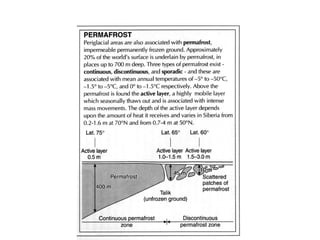

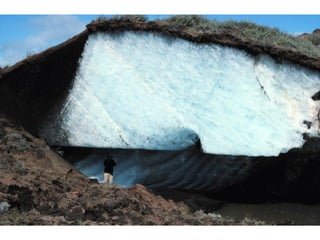

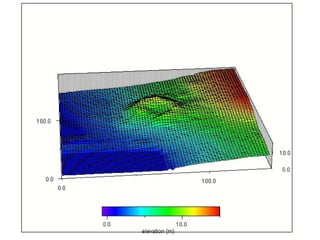

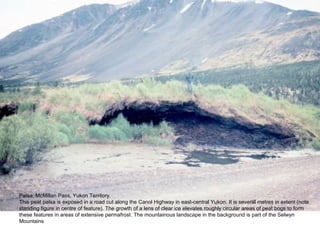

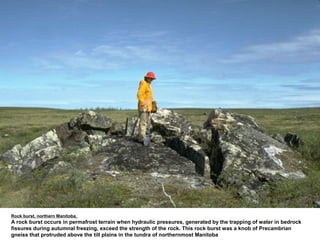

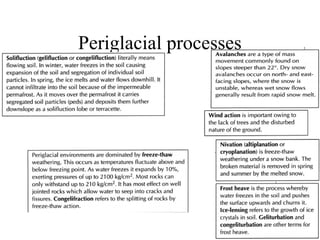

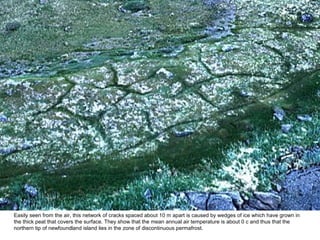

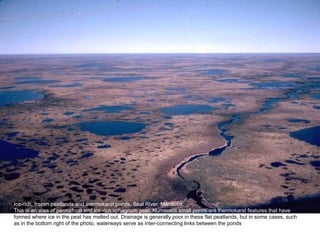

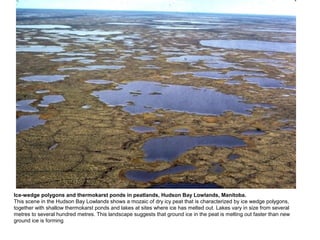

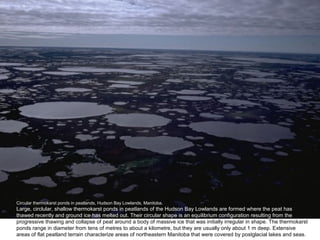

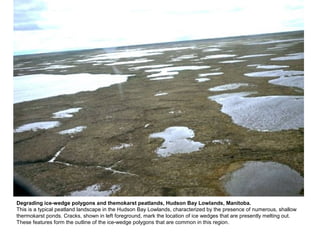

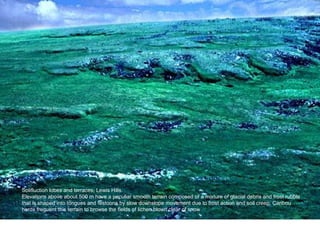

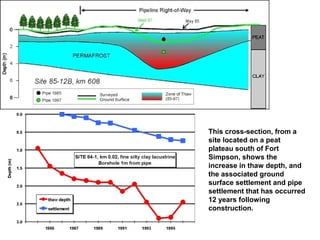

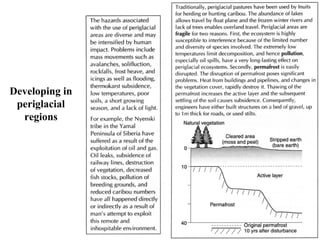

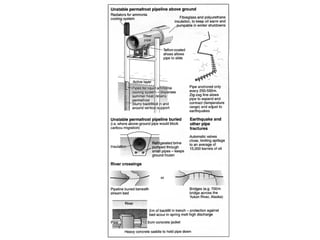

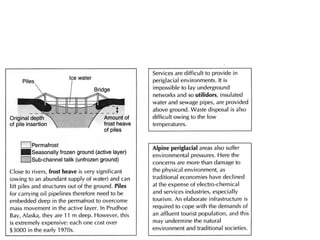

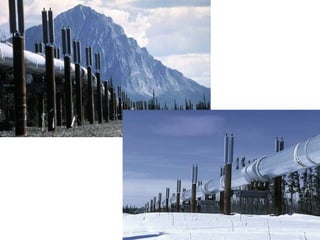

Periglacial environments are defined by the presence of permafrost. Unique landforms such as pingos, palsas, patterned ground including ice-wedge polygons, and thermokarst features form due to freezing and thawing of ice in soils. Permafrost poses challenges for infrastructure development but techniques like using thermosyphons can help ensure stability.