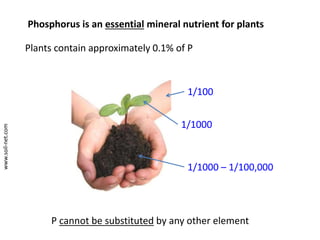

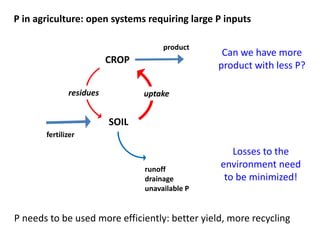

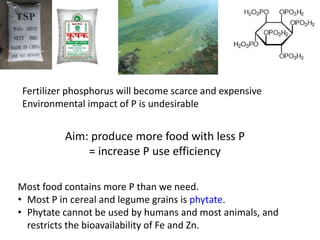

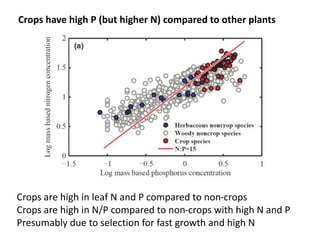

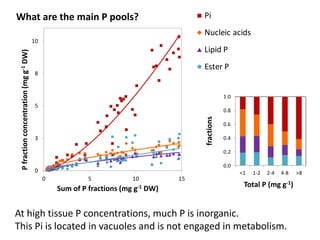

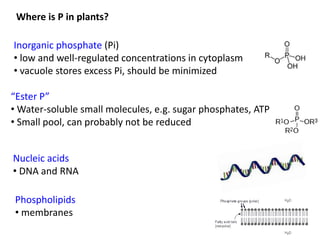

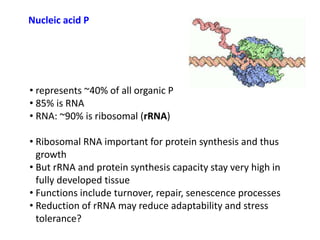

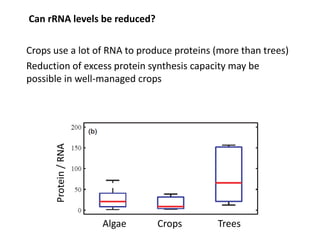

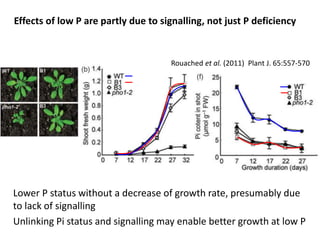

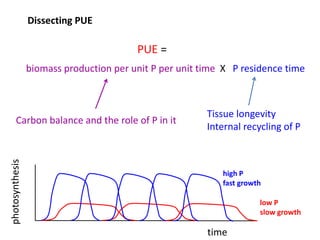

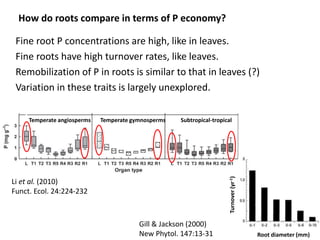

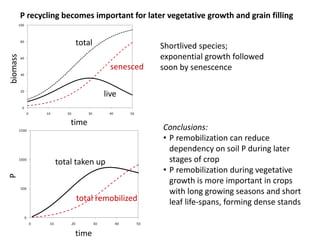

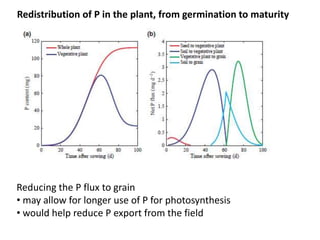

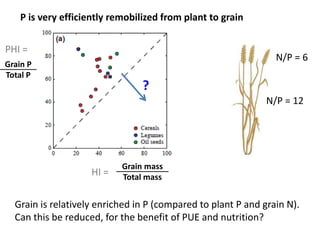

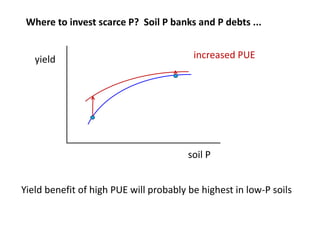

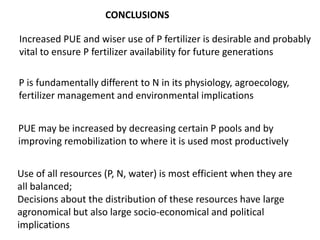

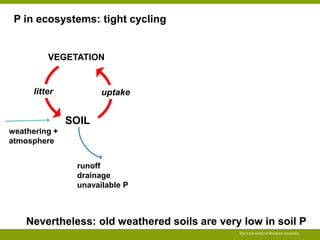

This document summarizes a presentation about opportunities to improve phosphorus-use efficiency in crop plants. It discusses how phosphorus is essential for plants but finite reserves exist, creating a need to produce more food with less phosphorus input. Various strategies are presented to improve phosphorus acquisition and utilization efficiency, such as increasing phosphorus recycling within plants and reducing phosphorus concentrations in plant tissues like leaves, roots and grain.

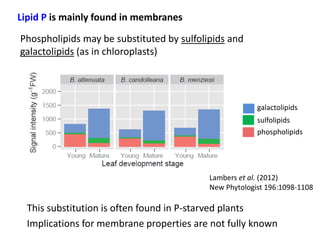

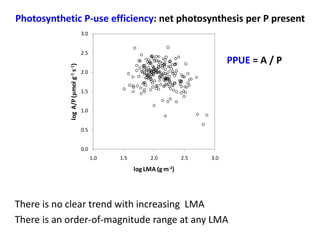

![Photosynthetic P-use efficiency = net photosynthesis per P present

Global patterns using the “leaf economics spectrum” dataset

(Wright et al. (2004) Nature 428:821-827)

1.0

0.5

0.0

-0.5

-1.0

-1.5

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5

log [P] (mg g-1)

log LMA (g m-2)

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

log Amass (nmol g-1 s-1)

Higher Leaf Dry Mass per Area (LMA): thicker, denser leaves

Longer leaf lifespan

log LMA (g m-2)

P concentration Photosynthesis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-18-320.jpg)

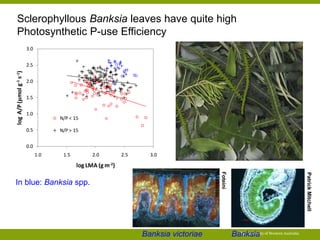

![Some of the variation in A/P at a given LMA is related with [N]

A/P (μmol g-1 s-1)

Leaf N/P > 15

“P-limited”

129.4

Leaf N/P < 15

“N-limited”

59.3

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

N/P < 15

N/P > 15

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

log A/P (μmol g-1 s-1)

log LMA (g m-2)

Much higher Photosynthetic P-use Efficiency in “P-limited” than “N-limited”

plants

Implication for agronomy: plant production is most efficient when all

resources are used optimally at all times](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-20-320.jpg)

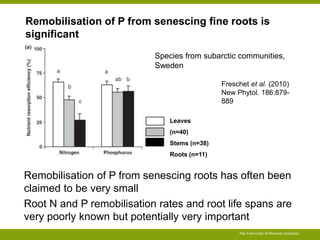

![An extreme leaf-root contrast in PUE in a low-P environment

Trait Banksia leaf Banksia cluster root

[P], mg g-1 0.2 1

Life span, yr 3 0.1

P remobilisation, % 80 90

P cost, mg g-1 yr-1 0.01 1.0

P cost per unit standing crop per year may be 100X more for cluster roots than leaves](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-24-320.jpg)

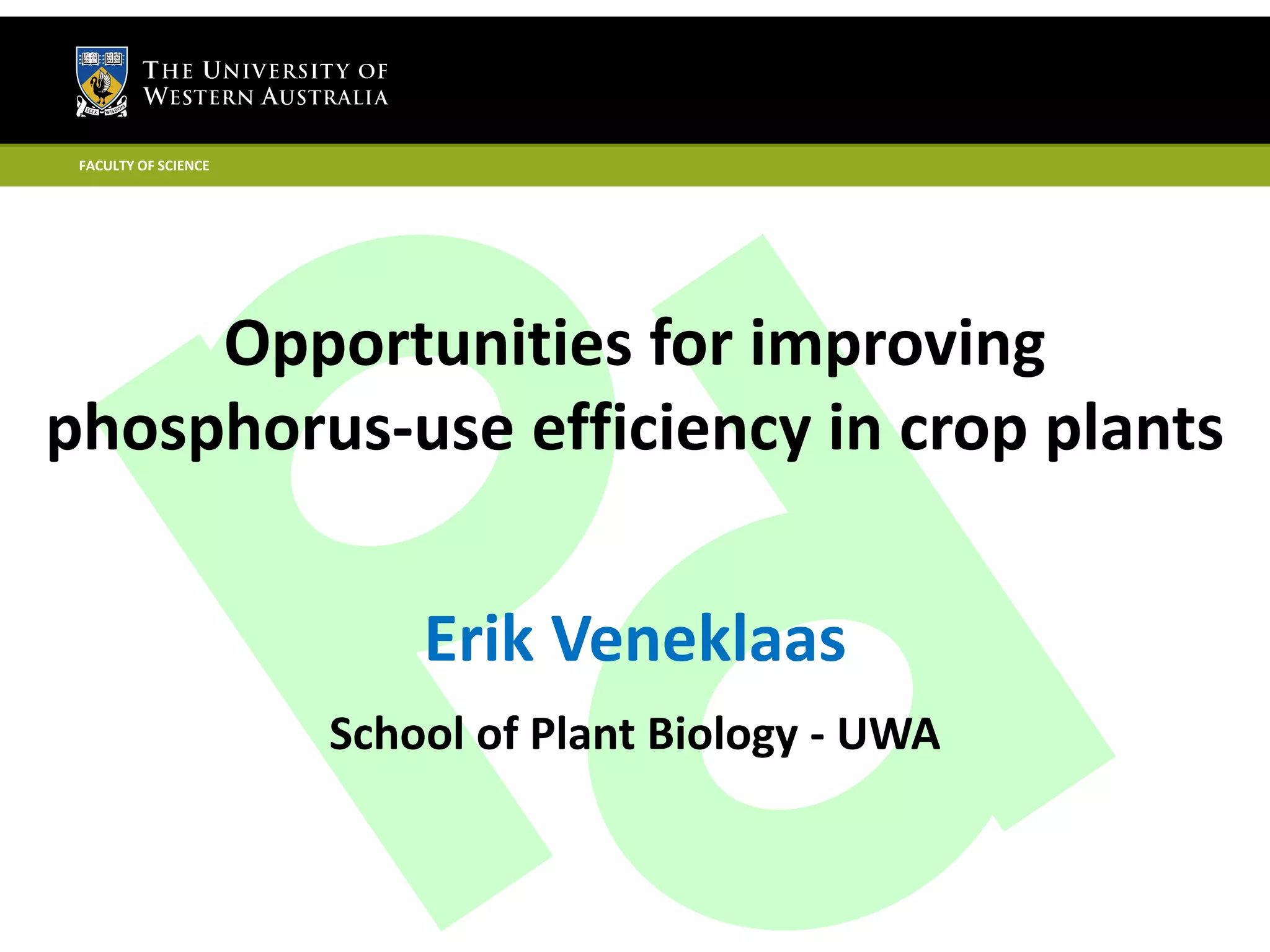

![P recycling in the vegetative plant

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

remobilisation = 80%

0 10 20 30

% P from remobilisation

time

current

cumulative

Remobilization only starts

contributing to P economy

when there is senescing

tissue

Even with constant growth rate, senescence, [P] and remobilization:

• % P derived from remobilization increases only slowly over time

• total % P derived from remobilization for vegetative growth is

considerably less than the % P remobilized from senescing biomass](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-26-320.jpg)

![[P] in grain has already been reduced through selection

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Domestication of wheat Historic wheat cultivars

diploid tetraploid hexaploid

P concentration in grain (%)

high P

low P

Calderini et al. (1995) Ann. Bot. 76:315-322

Batten et al. (1986) Ann. Bot. 58:49-59

Mainly due to ‘dilution’ (more starch).

Further progress may be possible; physiological limits are unknown

but links with N and C are likely.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-31-320.jpg)

![“Ideotype” for efficient use of P

Fast and early P uptake and efficient internal recycling of P

• P will be in plant for a longer time to be used

productively

High photosynthesis at low P

• No excess P in tissues (including roots and stems)

• More productive use of P

Low grain P • More P returns to the soil

• Less P is lost to the environment

• Improved nutritional value

[Need to watch possible early vigour penalty]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-32-320.jpg)

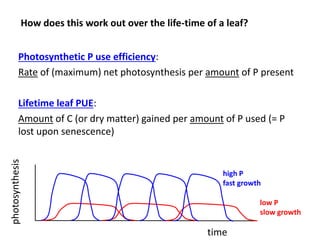

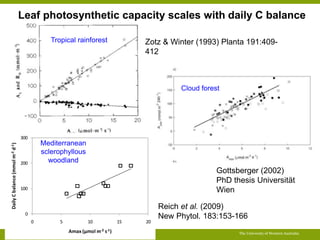

![PUE over the life-time of a leaf (in the context of

the Leaf Economic Spectrum)

C balance: High-LMA leaves live longer but have lower

rates of photosynthesis …

P balance: High-LMA leaves have lower [P] and may

have higher remobilisation …

The University of Western Australia

150

100

50

0

0 100 200 300 400

LL (mo)

LMA (g m-2)

500

400

300

200

100

0

0 100 200 300 400

Amass (nmol g-1 s-1)

LMA (g m-2)

5

4

3

2

1

0

0 100 200 300 400

[P] (mg g-1)

LMA (g m-2)

Data: glopnet database – Wright et al. (2004) Nature

428:821-827](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-40-320.jpg)

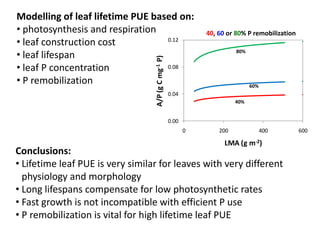

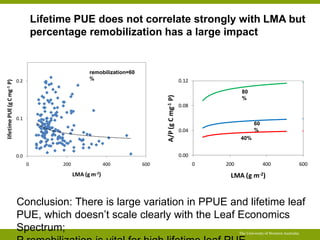

![Summary lifetime leaf PUE: comparing leaves with LMA 100 and 200 g

m-2

(P remobilisation 60%)

[P] X 0.57

lifetime P balance X 1.85

LMA 100 LMA 200

The University of Western Australia

30

20

10

0

LL X 3.3

LMA 100 LMA 200

100

50

0

Amax X 0.59

LMA 100 LMA 200

15

10

5

0

lifetime C balance X 2.01

LMA 100 LMA 200

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

LMA 100 LMA 200

200

150

100

50

0

0.06

0.04

0.02

0.00

lifetime PUE X 1.09

LMA 100 LMA 200

Despite large differences in morphology and physiology, PUE differs by

less than 10%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-44-320.jpg)

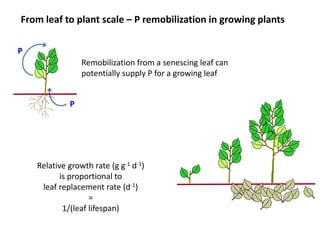

![P required to maintain biomass (e.g. mature perennial plants)

The University of Western Australia

1000

800

600

400

200

0

P

remobilisation

20%

40%

60%

80%

0 10 20 30

Annual P cost (% of P content)

Tissue lifespan (months)

No net growth – maintenance

only;

P uptake required to maintain

same amount of tissue with same

[P]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/veneklaaspue2014-140923135409-phpapp02/85/Opportunities-for-improving-phosphorus-use-efficiency-in-crop-plants-47-320.jpg)