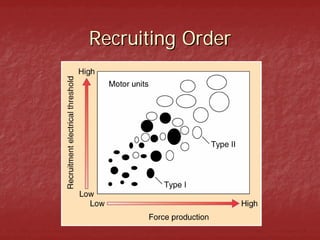

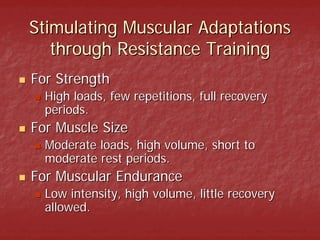

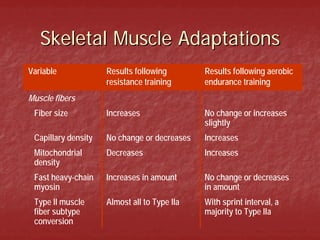

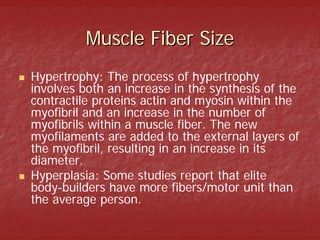

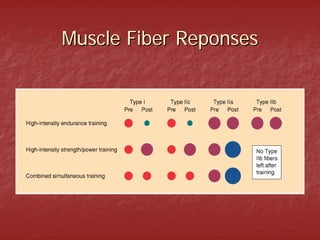

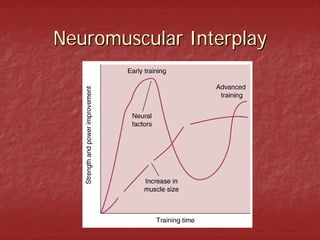

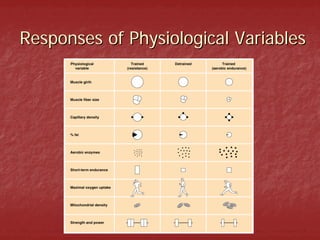

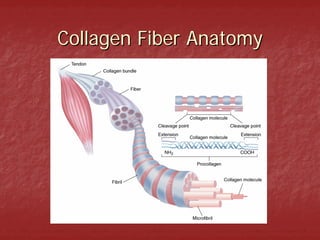

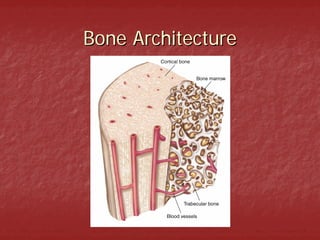

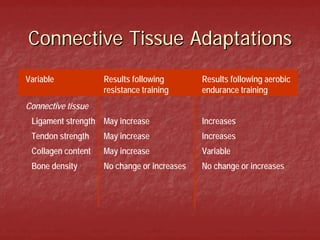

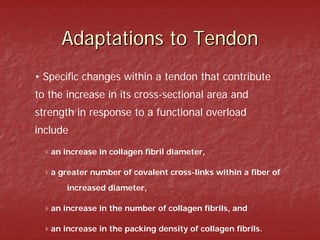

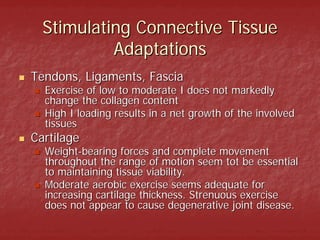

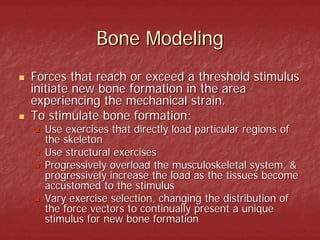

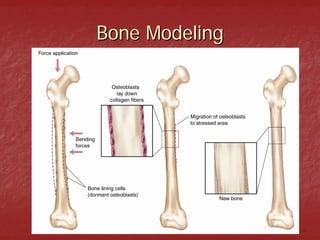

This document summarizes the neural and muscular adaptations that occur from resistance and aerobic training. It discusses how the central nervous system adapts through improved motor unit recruitment. Resistance training causes muscle fiber hypertrophy and increases in strength, while aerobic training improves aerobic capacity without enhancing muscle size. Both can promote a fast to slow shift in fiber types. Connective tissues like tendons and ligaments strengthen through increased collagen from high intensity loading. Bone modeling occurs when forces exceed threshold levels, stimulating new formation.