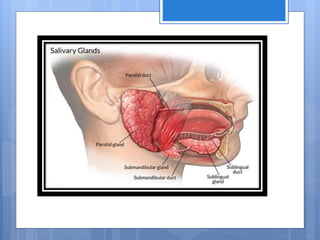

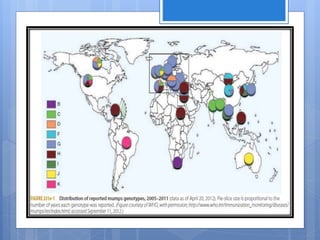

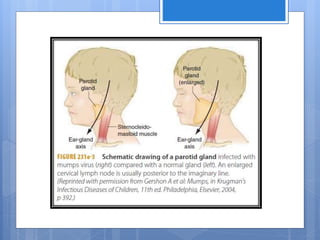

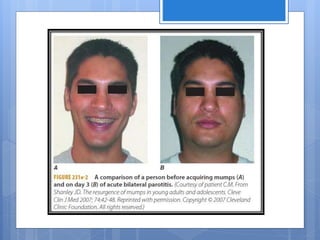

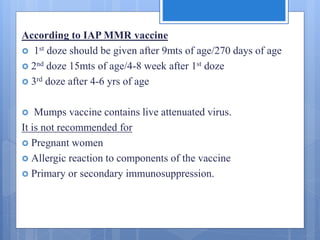

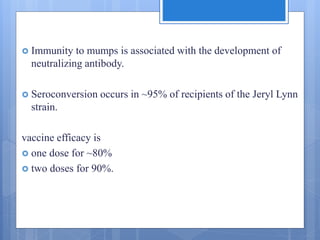

Mumps is caused by a paramyxovirus that typically presents as swelling of the parotid or other salivary glands. It is spread through respiratory droplets and saliva. While most infections are asymptomatic or mild, complications can include orchitis, meningitis, and deafness. Diagnosis is made through PCR detection of viral RNA or serology. Treatment is supportive and includes analgesics. Vaccination with the live attenuated Jeryl Lynn strain as part of the MMR vaccine provides around 90% protection with two doses and has significantly reduced mumps cases worldwide.