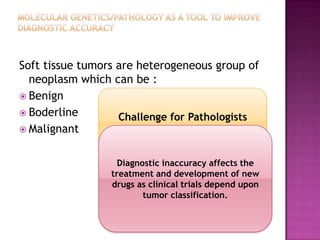

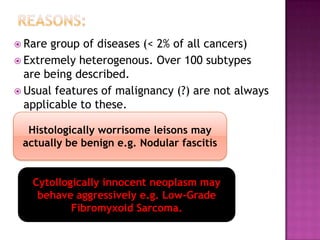

This document discusses the utility of integrating molecular genetics with soft tissue pathology. Key points include:

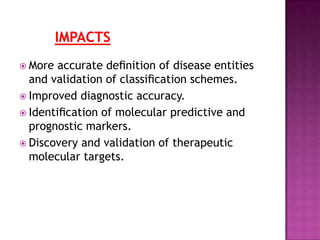

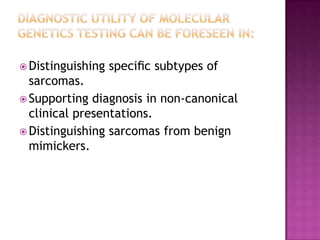

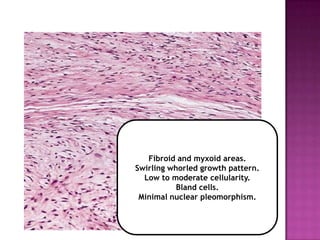

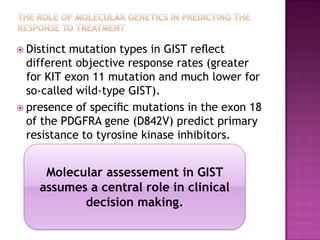

1) Molecular genetics can help more accurately define disease entities, improve diagnostic accuracy, and identify prognostic and therapeutic targets.

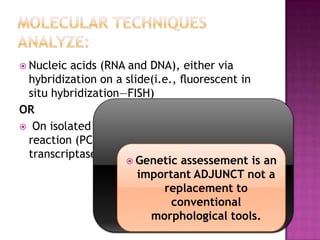

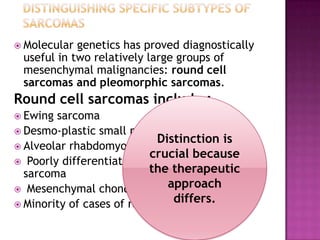

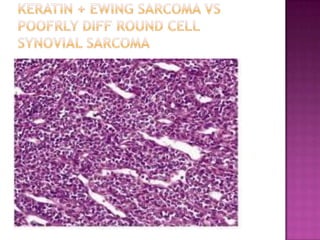

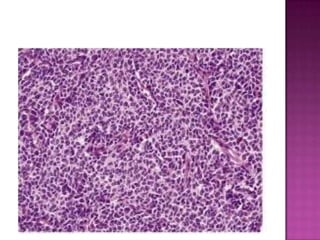

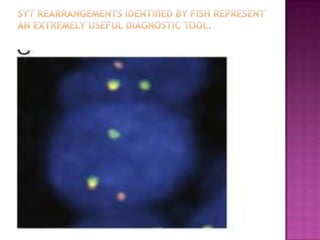

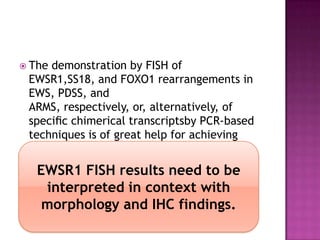

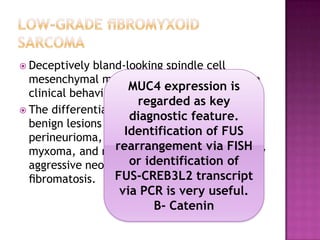

2) Techniques like FISH and PCR are useful for distinguishing subtypes of sarcomas and supporting diagnoses, especially in non-canonical cases.

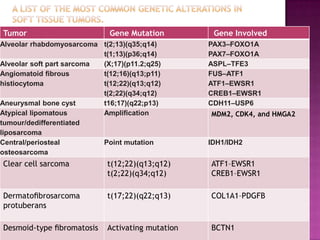

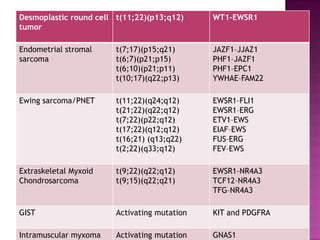

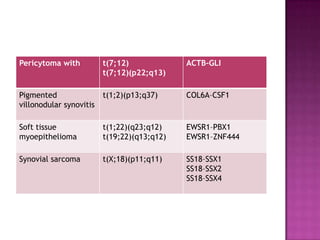

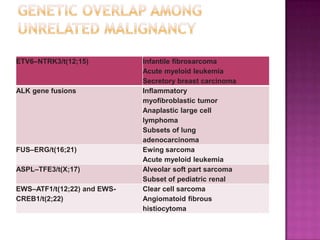

3) Specific gene fusions and mutations have been identified that are diagnostic for entities like Ewing sarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and GIST.

4) While molecular findings cannot replace morphology, genetics provides an important adjunct for diagnosis, especially in challenging cases. The integration of both disciplines has enhanced understanding and classification of soft