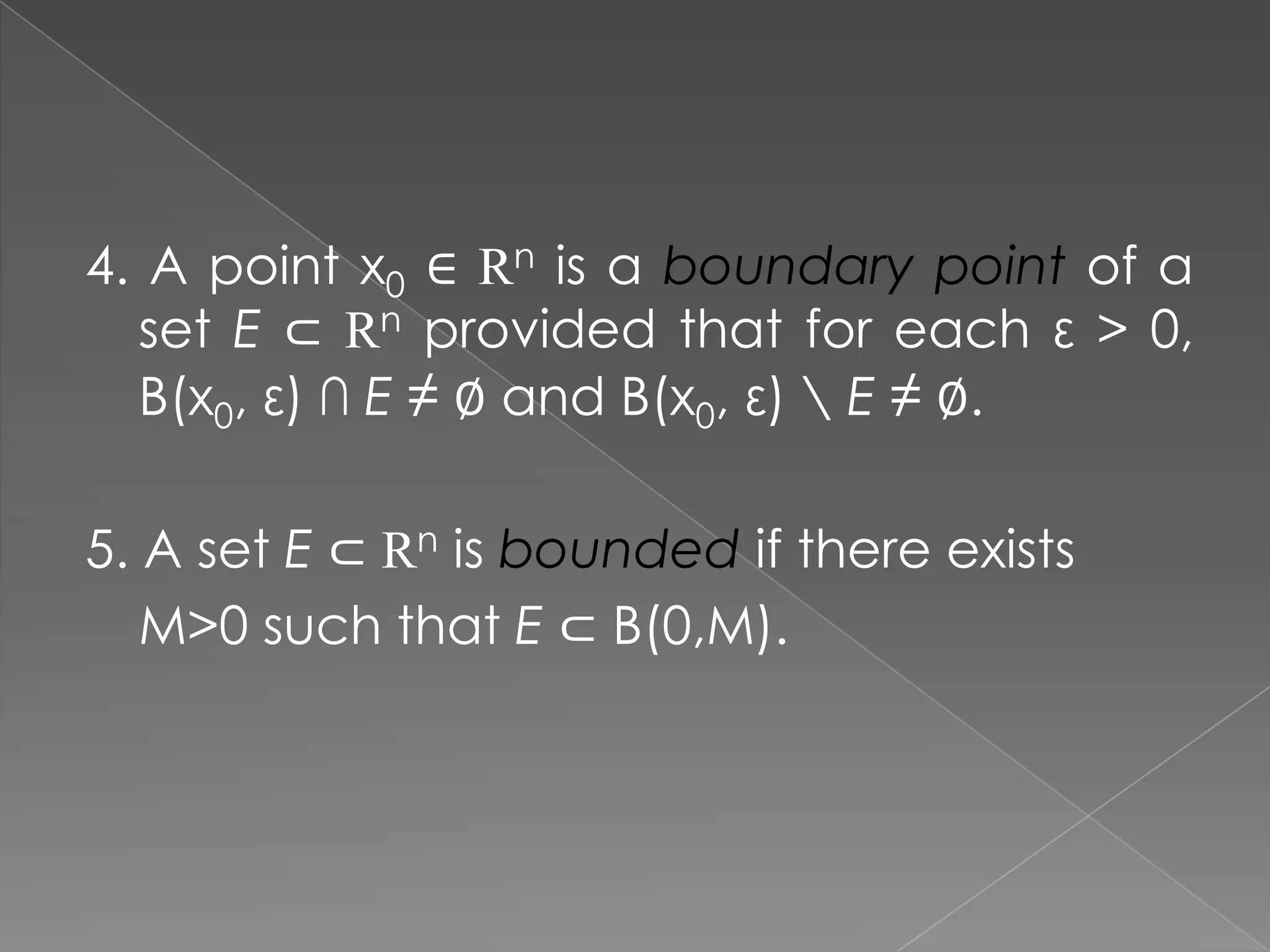

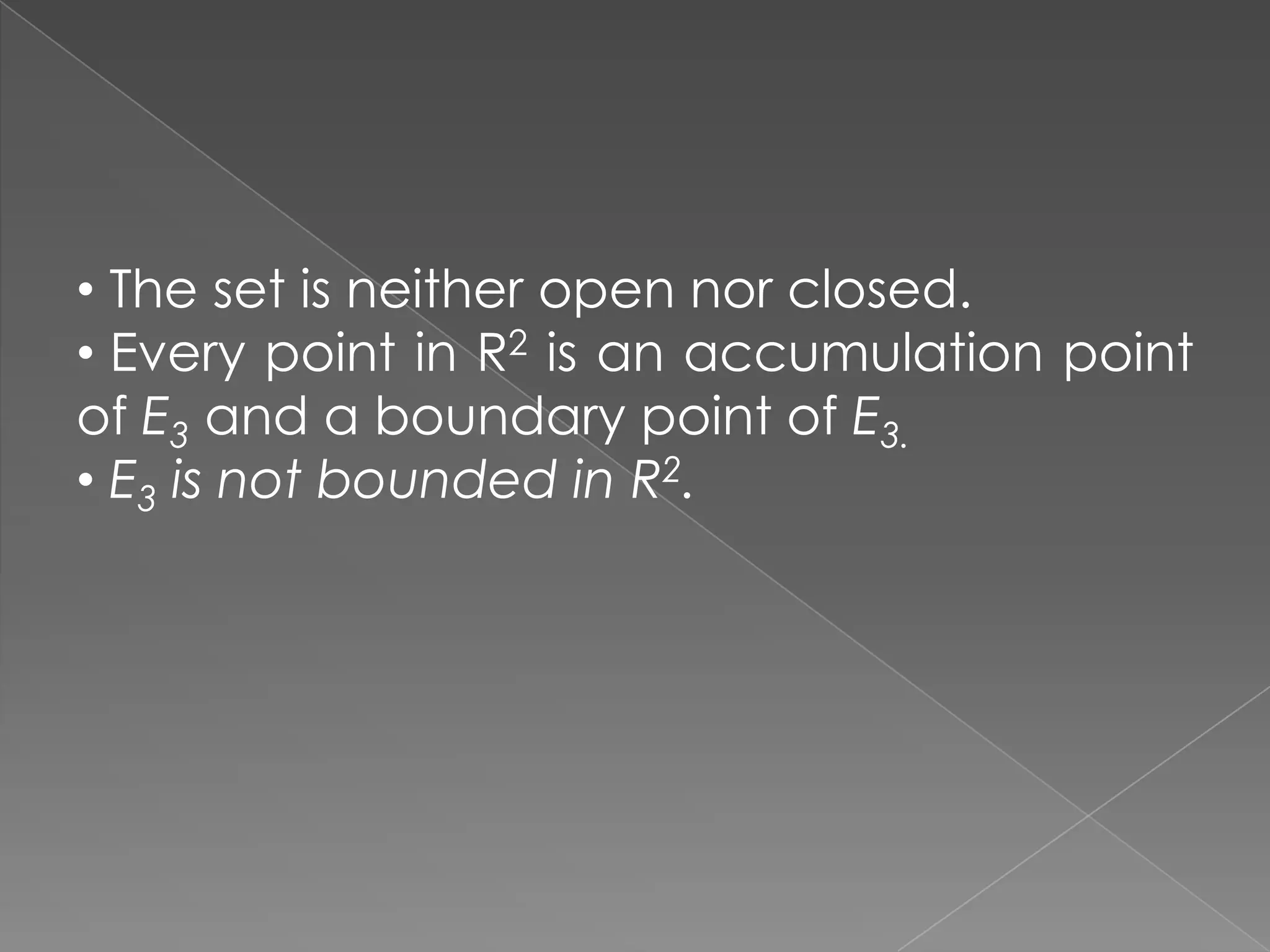

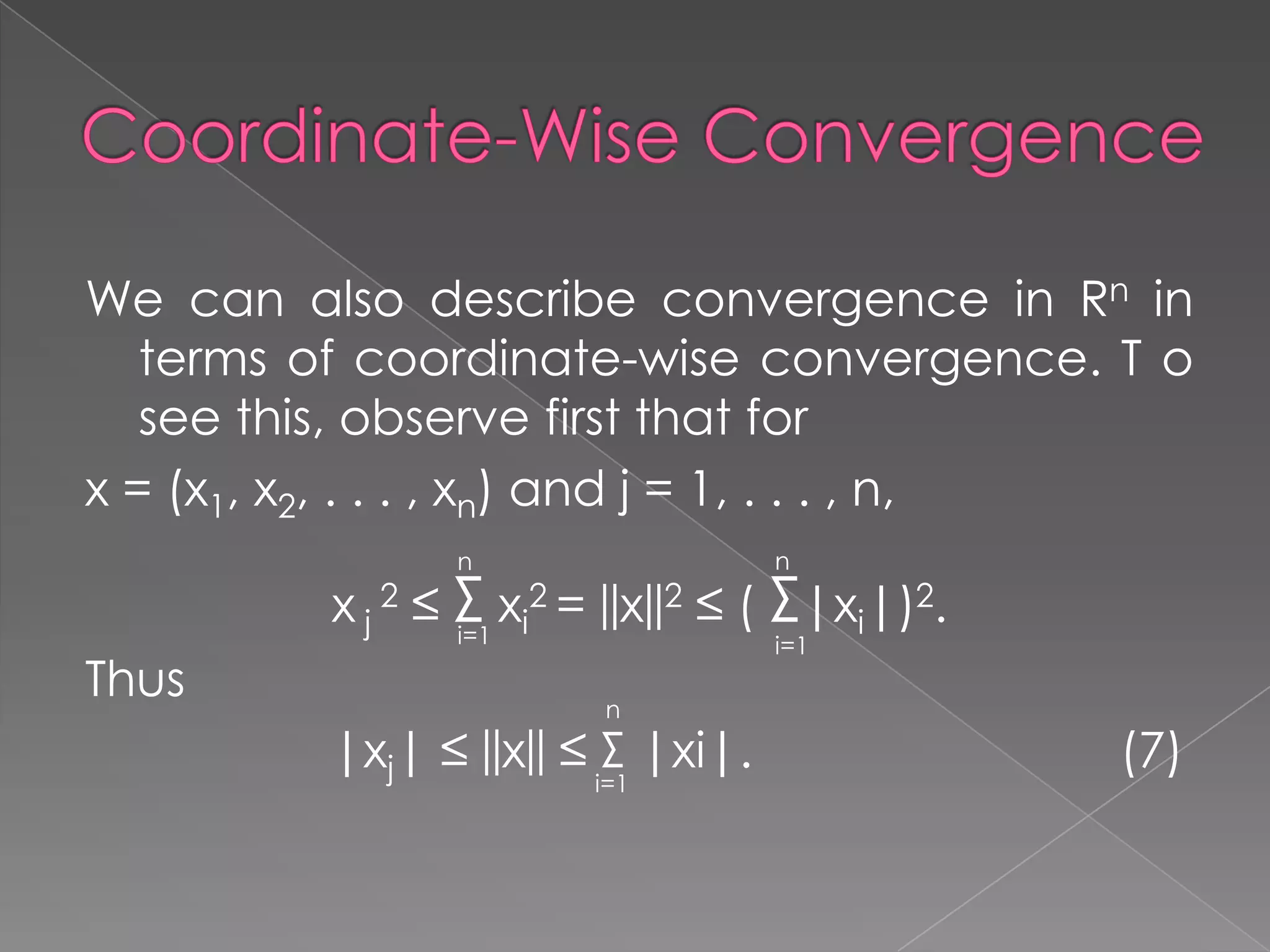

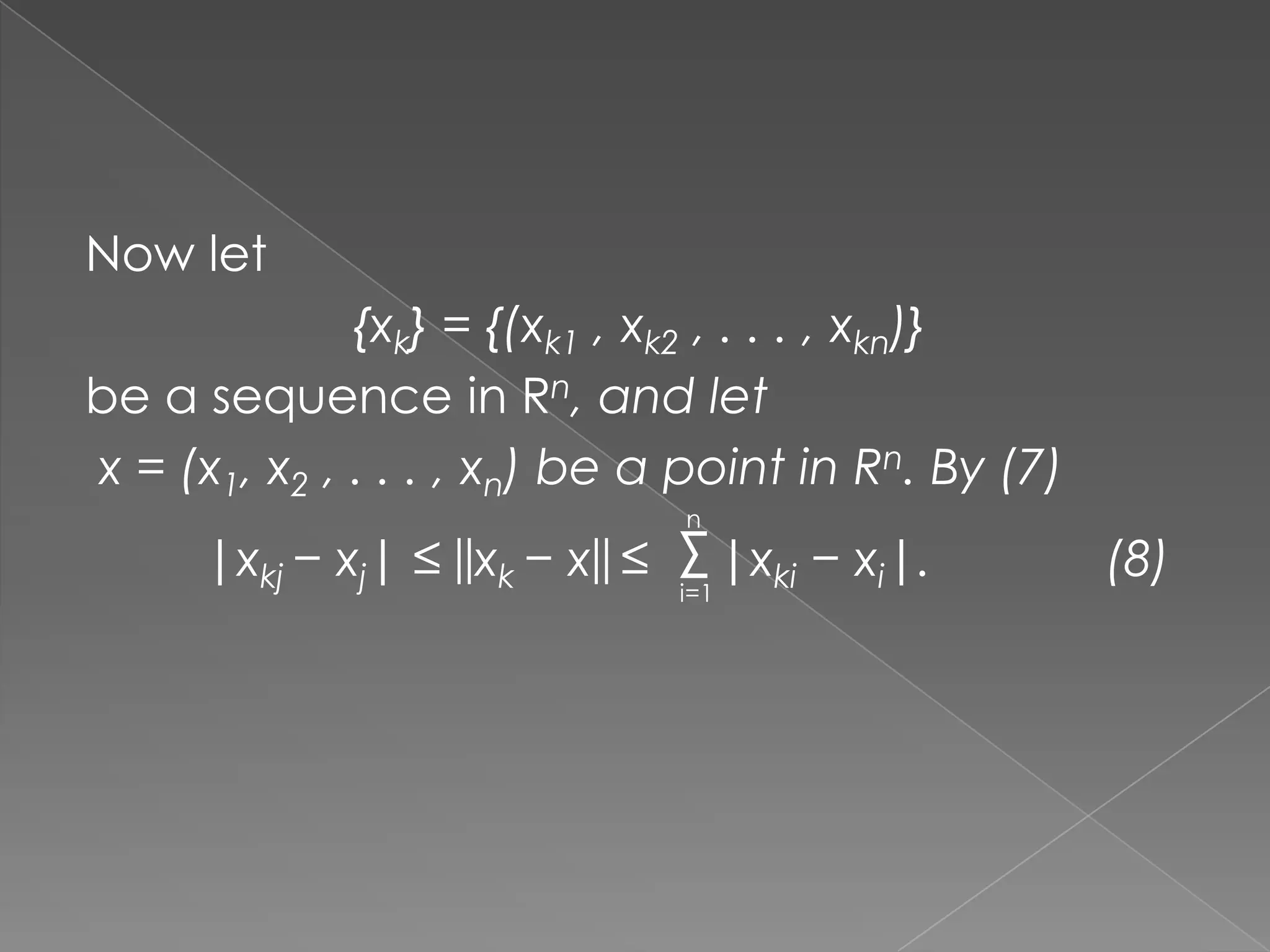

The document defines key concepts related to sequences and limits in multivariable calculus including open balls, open and closed sets, accumulation points, bounded sequences, and convergence of sequences in Rn. It proves that a set is closed if and only if it contains all its limit points. It also proves that every bounded sequence in Rn contains a convergent subsequence using the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem and taking subsequences of the coordinates.