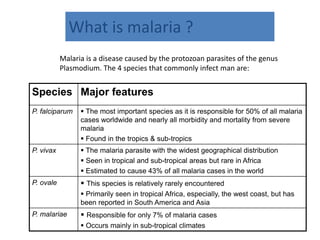

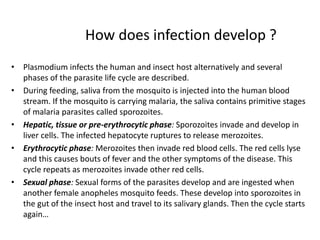

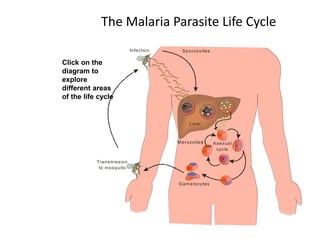

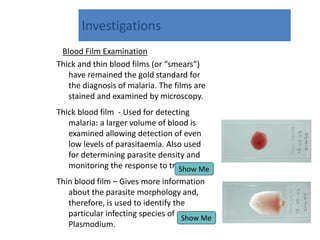

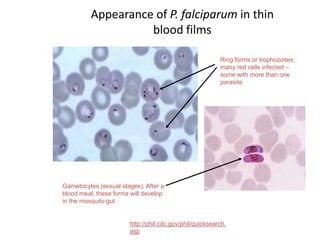

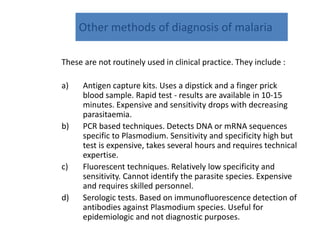

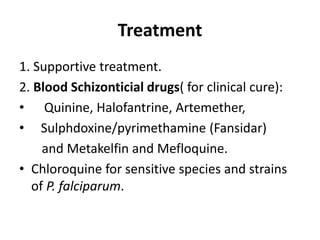

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted via mosquito bites. P. falciparum is the most deadly species, responsible for over 50% of cases and nearly all malaria deaths. It develops through liver and blood stages in humans. Symptoms include fever, chills, vomiting and can progress to severe complications without treatment. Diagnosis involves blood smears examined microscopically for parasite forms. Treatment aims for clinical cure with antimalarial drugs and eradication of dormant stages to prevent relapse. Naturally acquired immunity develops in endemic areas but young children and pregnant women remain most vulnerable.