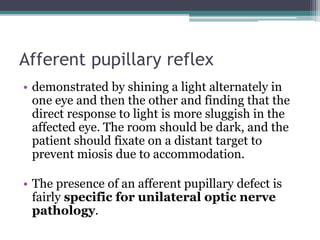

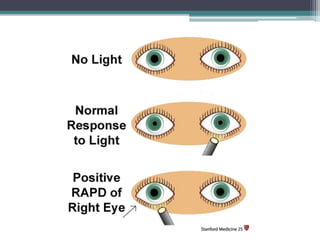

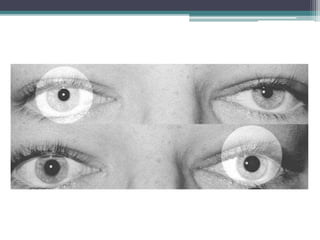

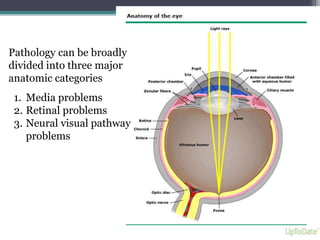

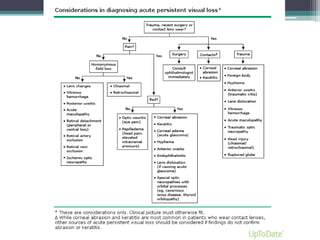

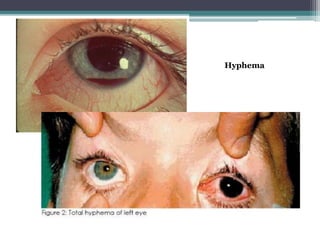

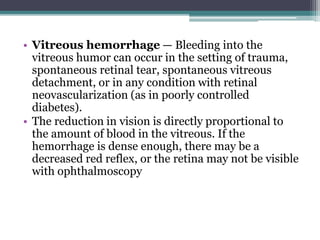

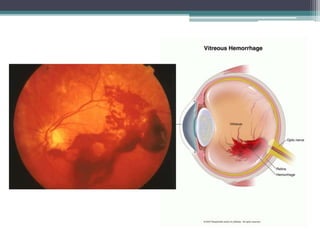

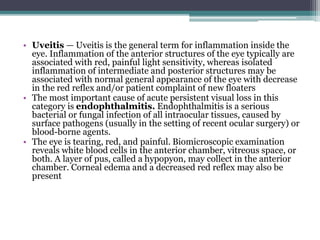

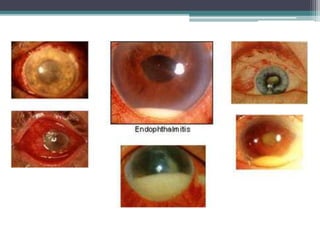

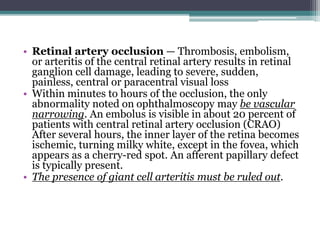

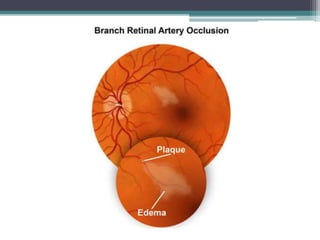

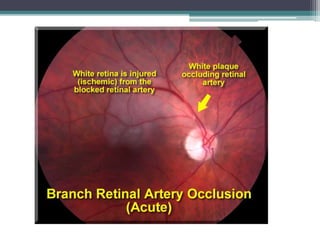

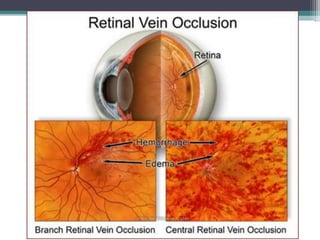

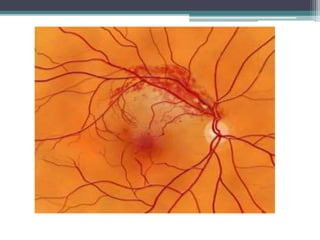

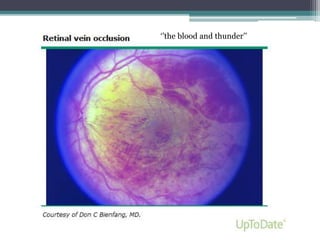

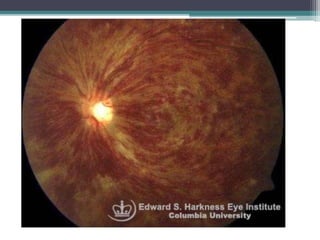

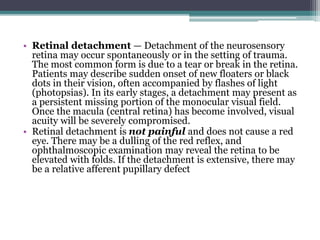

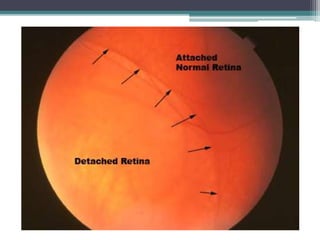

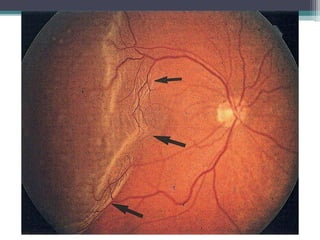

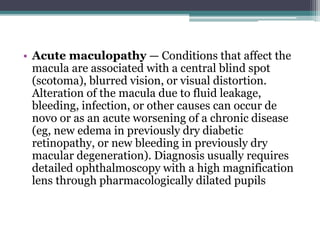

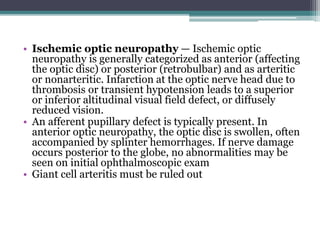

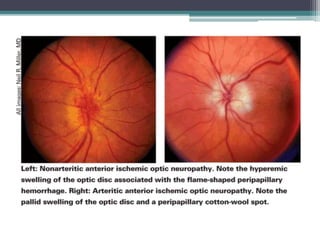

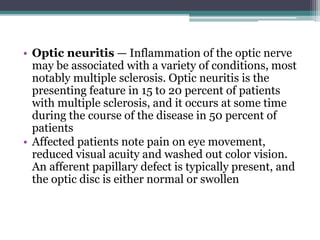

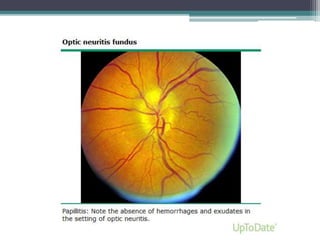

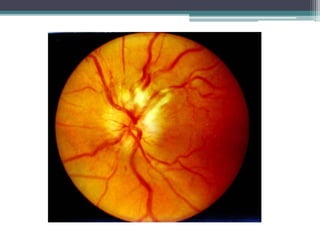

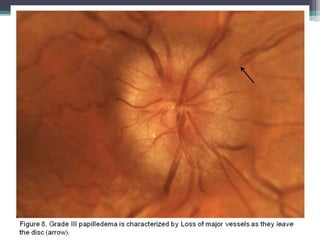

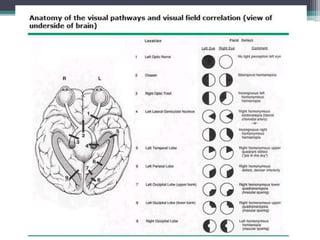

This document discusses the evaluation and management of sudden visual loss. It begins by distinguishing between acute transient visual loss lasting less than 24 hours and acute persistent visual loss lasting at least 24 hours. Important aspects of the history and examination are outlined. Causes of visual loss are then categorized as media problems, retinal problems, neural pathway problems, and psychogenic problems. Specific conditions are described within each category along with distinguishing examination findings and appropriate management. Immediate treatment is recommended for conditions such as central retinal artery occlusion and acute angle closure glaucoma, while other conditions require emergent or urgent referral.