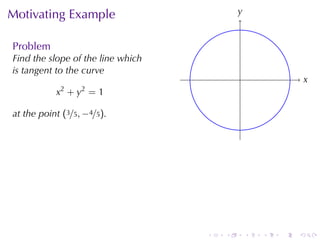

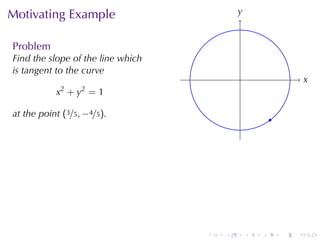

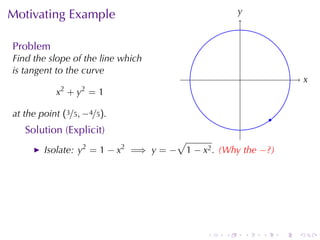

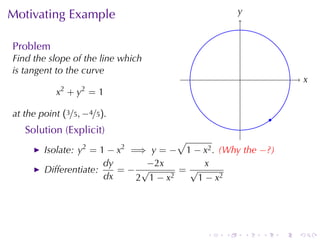

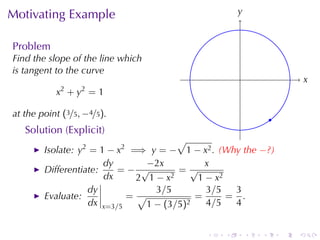

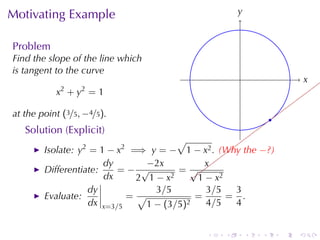

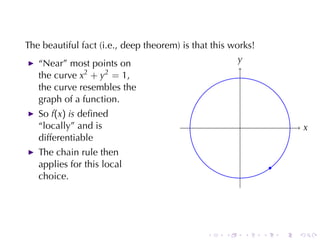

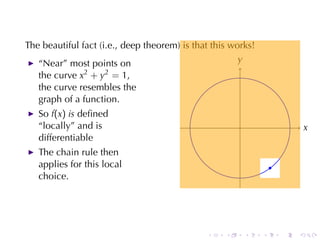

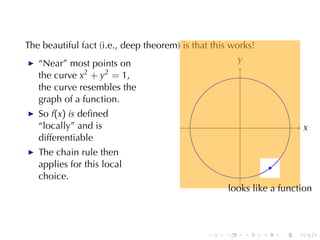

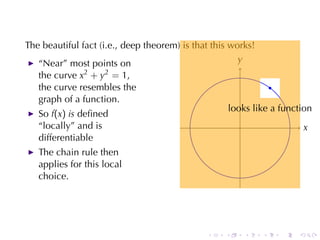

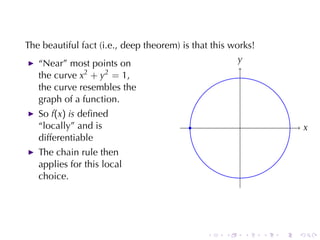

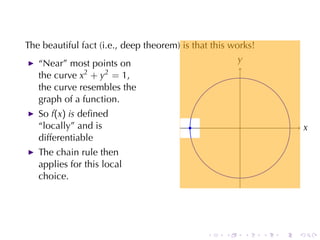

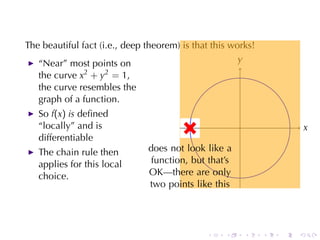

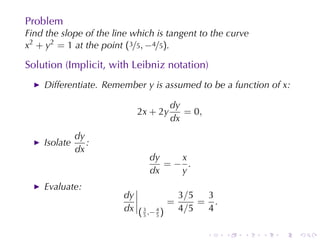

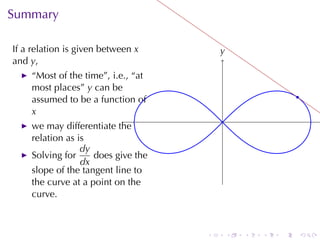

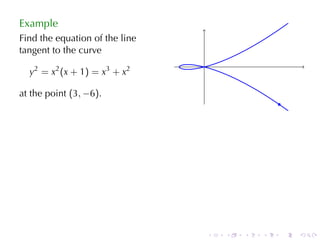

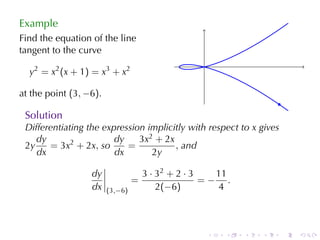

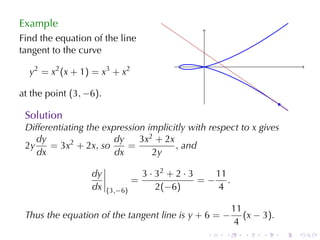

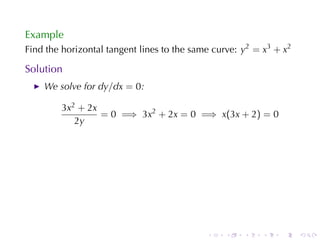

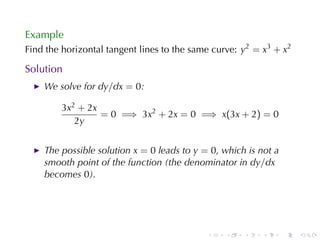

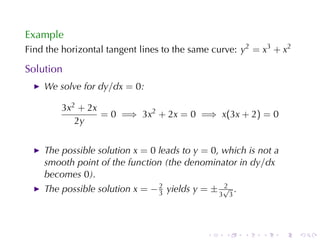

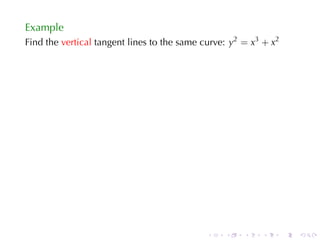

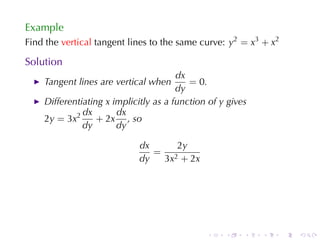

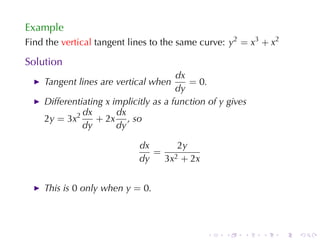

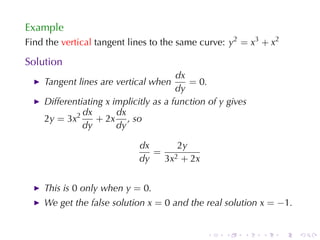

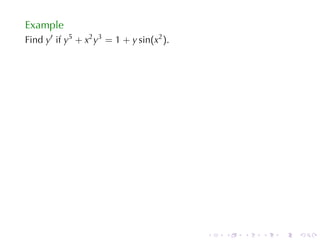

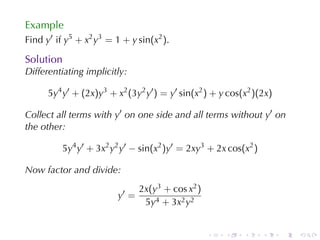

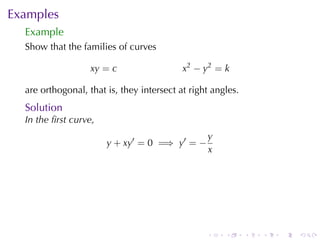

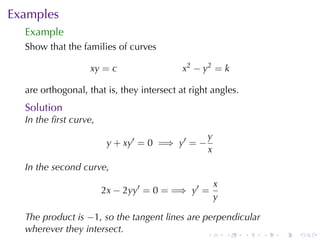

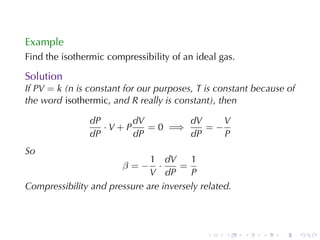

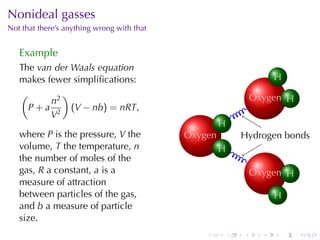

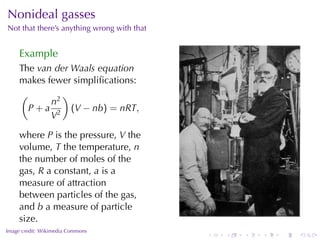

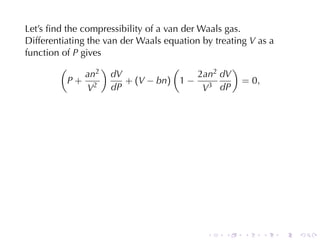

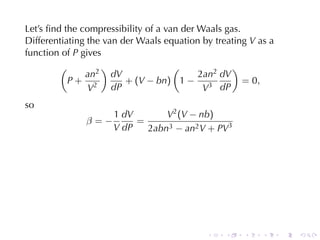

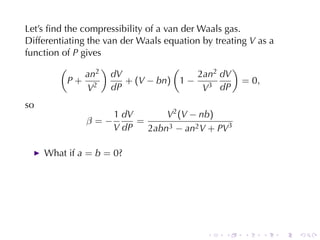

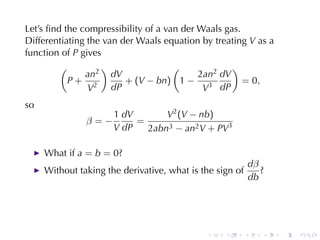

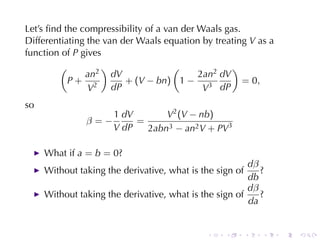

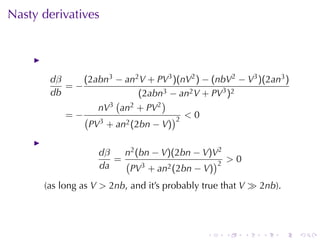

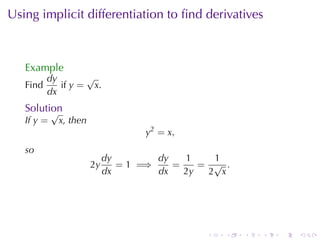

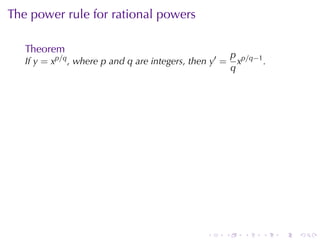

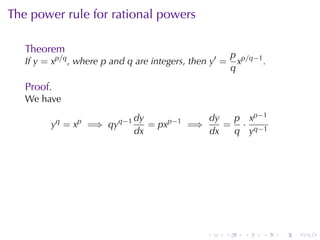

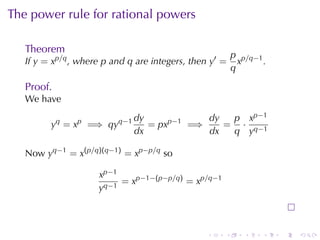

The document discusses implicit differentiation in calculus, particularly focusing on finding slopes of tangent lines to curves defined by implicit equations. It provides examples, solutions, and theorems about the nature of tangent lines, including vertical and horizontal tangents, as well as orthogonal trajectories. The concept of differentiability of relations and applications in solving problems related to ideal and non-ideal gases is also presented.