This document summarizes a calculus lecture on the Mean Value Theorem. It begins with announcements about exams and assignments. It then outlines the topics to be covered: Rolle's Theorem and the Mean Value Theorem, applications of the MVT, and why the MVT is important. It provides heuristic motivations and mathematical statements of Rolle's Theorem and the Mean Value Theorem. It also includes a proof of the Mean Value Theorem using Rolle's Theorem.

![Mathematical Statement of Rolle’s Theorem

Theorem (Rolle’s Theorem)

Let f be continuous on [a, b]

and differentiable on (a, b).

Suppose f (a) = f (b). Then

there exists a point c in (a, b)

such that f (c) = 0.

a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-6-2048.jpg)

![Mathematical Statement of Rolle’s Theorem

Theorem (Rolle’s Theorem)

c

Let f be continuous on [a, b]

and differentiable on (a, b).

Suppose f (a) = f (b). Then

there exists a point c in (a, b)

such that f (c) = 0.

a b

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 6 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-7-2048.jpg)

![Flowchart proof of Rolle’s Theorem

endpoints

Let c be Let d be

are max

the max pt the min pt

and min

f is

is c an is d an

yes yes constant

endpoint? endpoint?

on [a, b]

no no

f (x) ≡ 0

f (c) = 0 f (d) = 0

on (a, b)

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 8 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-8-2048.jpg)

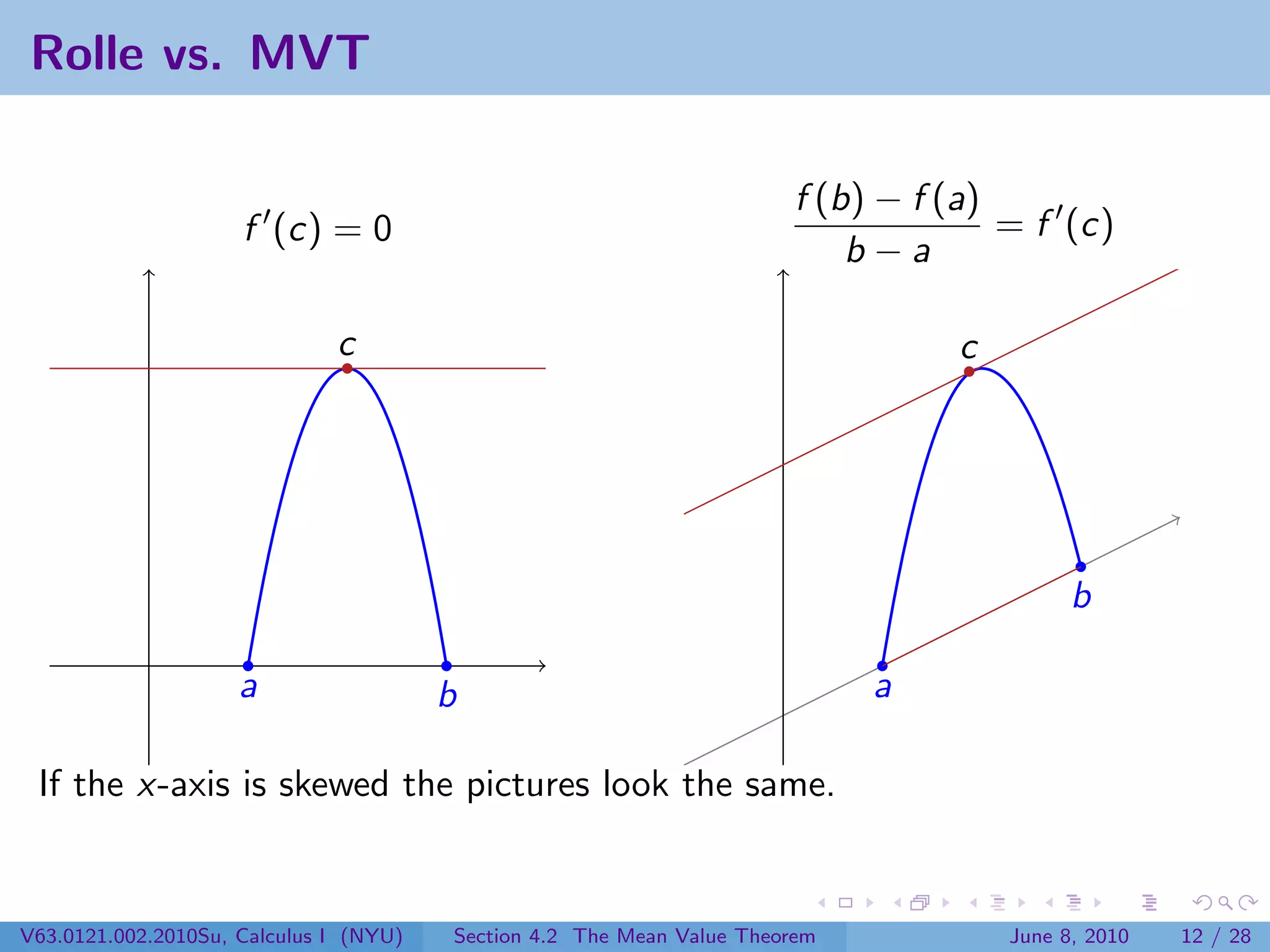

![The Mean Value Theorem

Theorem (The Mean Value Theorem)

Let f be continuous on [a, b]

and differentiable on (a, b).

Then there exists a point c in

(a, b) such that

f (b) − f (a) b

= f (c).

b−a

a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-11-2048.jpg)

![The Mean Value Theorem

Theorem (The Mean Value Theorem)

Let f be continuous on [a, b]

and differentiable on (a, b).

Then there exists a point c in

(a, b) such that

f (b) − f (a) b

= f (c).

b−a

a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-12-2048.jpg)

![The Mean Value Theorem

Theorem (The Mean Value Theorem)

c

Let f be continuous on [a, b]

and differentiable on (a, b).

Then there exists a point c in

(a, b) such that

f (b) − f (a) b

= f (c).

b−a

a

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 11 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-13-2048.jpg)

![Proof of the Mean Value Theorem

Proof.

The line connecting (a, f (a)) and (b, f (b)) has equation

f (b) − f (a)

y − f (a) = (x − a)

b−a

Apply Rolle’s Theorem to the function

f (b) − f (a)

g (x) = f (x) − f (a) − (x − a).

b−a

Then g is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b) since f is.

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 13 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-18-2048.jpg)

![Proof of the Mean Value Theorem

Proof.

The line connecting (a, f (a)) and (b, f (b)) has equation

f (b) − f (a)

y − f (a) = (x − a)

b−a

Apply Rolle’s Theorem to the function

f (b) − f (a)

g (x) = f (x) − f (a) − (x − a).

b−a

Then g is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b) since f is. Also

g (a) = 0 and g (b) = 0 (check both)

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 13 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-19-2048.jpg)

![Proof of the Mean Value Theorem

Proof.

The line connecting (a, f (a)) and (b, f (b)) has equation

f (b) − f (a)

y − f (a) = (x − a)

b−a

Apply Rolle’s Theorem to the function

f (b) − f (a)

g (x) = f (x) − f (a) − (x − a).

b−a

Then g is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b) since f is. Also

g (a) = 0 and g (b) = 0 (check both) So by Rolle’s Theorem there exists a

point c in (a, b) such that

f (b) − f (a)

0 = g (c) = f (c) − .

b−a

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 13 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-20-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to count solutions

Example

Show that there is a unique solution to the equation x 3 − x = 100 in the

interval [4, 5].

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 14 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-21-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to count solutions

Example

Show that there is a unique solution to the equation x 3 − x = 100 in the

interval [4, 5].

Solution

By the Intermediate Value Theorem, the function f (x) = x 3 − x must

take the value 100 at some point on c in (4, 5).

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 14 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-22-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to count solutions

Example

Show that there is a unique solution to the equation x 3 − x = 100 in the

interval [4, 5].

Solution

By the Intermediate Value Theorem, the function f (x) = x 3 − x must

take the value 100 at some point on c in (4, 5).

If there were two points c1 and c2 with f (c1 ) = f (c2 ) = 100, then

somewhere between them would be a point c3 between them with

f (c3 ) = 0.

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 14 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-23-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to count solutions

Example

Show that there is a unique solution to the equation x 3 − x = 100 in the

interval [4, 5].

Solution

By the Intermediate Value Theorem, the function f (x) = x 3 − x must

take the value 100 at some point on c in (4, 5).

If there were two points c1 and c2 with f (c1 ) = f (c2 ) = 100, then

somewhere between them would be a point c3 between them with

f (c3 ) = 0.

However, f (x) = 3x 2 − 1, which is positive all along (4, 5). So this is

impossible.

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 14 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-24-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to estimate

Example

We know that |sin x| ≤ 1 for all x. Show that |sin x| ≤ |x|.

Solution

Apply the MVT to the function f (t) = sin t on [0, x]. We get

sin x − sin 0

= cos(c)

x −0

for some c in (0, x). Since |cos(c)| ≤ 1, we get

sin x

≤ 1 =⇒ |sin x| ≤ |x|

x

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 15 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-26-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to estimate II

Example

Let f be a differentiable function with f (1) = 3 and f (x) < 2 for all x in

[0, 5]. Could f (4) ≥ 9?

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 16 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-27-2048.jpg)

![Using the MVT to estimate II

Example

Let f be a differentiable function with f (1) = 3 and f (x) < 2 for all x in

[0, 5]. Could f (4) ≥ 9?

Solution

y (4, 9)

By MVT

f (4) − f (1) (4, f (4))

= f (c) < 2

4−1

for some c in (1, 4). Therefore

f (4) = f (1) + f (c)(3) < 3 + 2 · 3 = 9.

(1, 3)

So no, it is impossible that f (4) ≥ 9.

x

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 16 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-28-2048.jpg)

![Why the MVT is the MITC

Most Important Theorem In Calculus!

Theorem

Let f = 0 on an interval (a, b). Then f is constant on (a, b).

Proof.

Pick any points x and y in (a, b) with x < y . Then f is continuous on

[x, y ] and differentiable on (x, y ). By MVT there exists a point z in (x, y )

such that

f (y ) − f (x)

= f (z) = 0.

y −x

So f (y ) = f (x). Since this is true for all x and y in (a, b), then f is

constant.

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 20 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-38-2048.jpg)

![MVT to the rescue

Lemma

Suppose f is continuous on [a, b] and lim+ f (x) = m. Then

x→a

f (x) − f (a)

lim+ = m.

x→a x −a

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 26 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-47-2048.jpg)

![MVT to the rescue

Lemma

Suppose f is continuous on [a, b] and lim+ f (x) = m. Then

x→a

f (x) − f (a)

lim+ = m.

x→a x −a

Proof.

Choose x near a and greater than a. Then

f (x) − f (a)

= f (cx )

x −a

for some cx where a < cx < x. As x → a, cx → a as well, so:

f (x) − f (a)

lim = lim+ f (cx ) = lim+ f (x) = m.

x→a+ x −a x→a x→a

V63.0121.002.2010Su, Calculus I (NYU) Section 4.2 The Mean Value Theorem June 8, 2010 26 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson19-themeanvaluetheoremslides-100610135342-phpapp02/75/Lesson-19-The-Mean-Value-Theorem-48-2048.jpg)