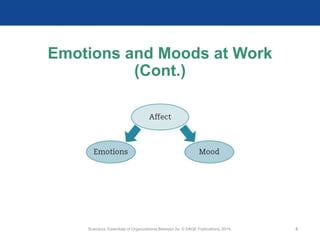

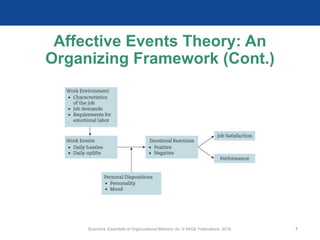

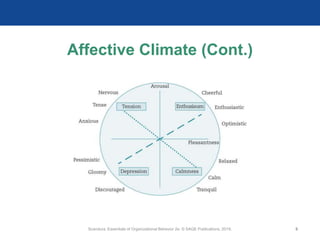

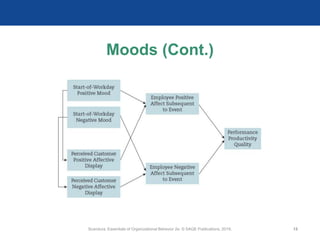

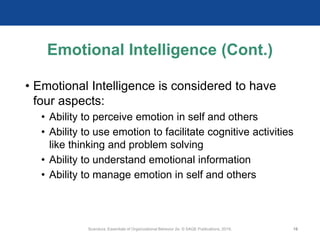

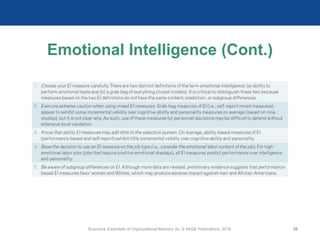

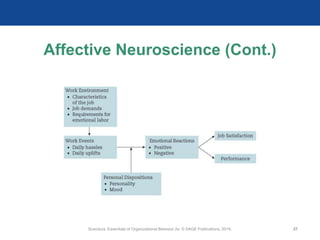

This document discusses emotions and moods in the workplace. It defines affect as the range of feelings employees experience, including emotions and moods. Emotions are triggered by specific events and brief, while moods are more general and last longer. Affective events theory examines how work environments and events trigger emotional reactions. The document also discusses emotional labor, intelligence, contagion, and neuroscience as they relate to emotions and moods at work.