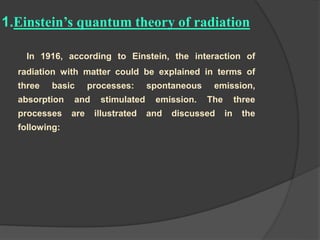

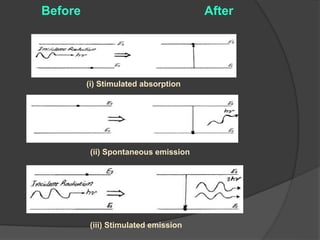

This document provides an overview of laser theory and applications across 4 chapters. Chapter 1 discusses the theory of lasing, including Einstein's theory of stimulated emission and how a population inversion enables light amplification in a laser medium. Chapter 2 will cover characteristics of laser beams. Chapter 3 will describe different types of laser sources. And Chapter 4 will discuss applications of laser technology.

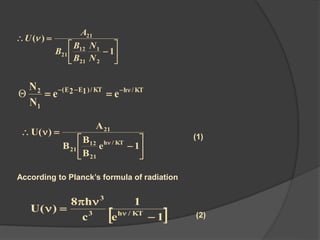

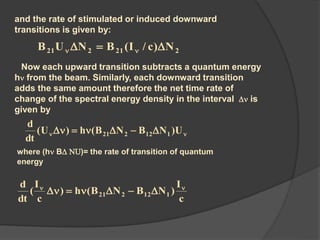

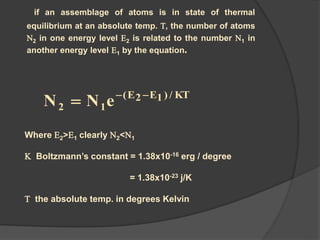

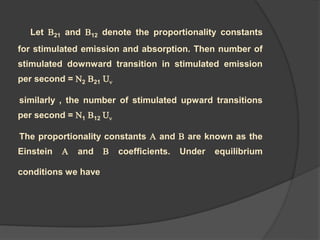

![by solving for U (density of the radiation) we obtain

U [N1 B12- N2 B21 ] = A21 N2

212121

212

BNBN

AN

)(U

N2 A21 + N2 B21 U =N1 B12 U

SP ST

A b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/laseritsapplications2-161217083535/85/Laser-its-applications-15-320.jpg)