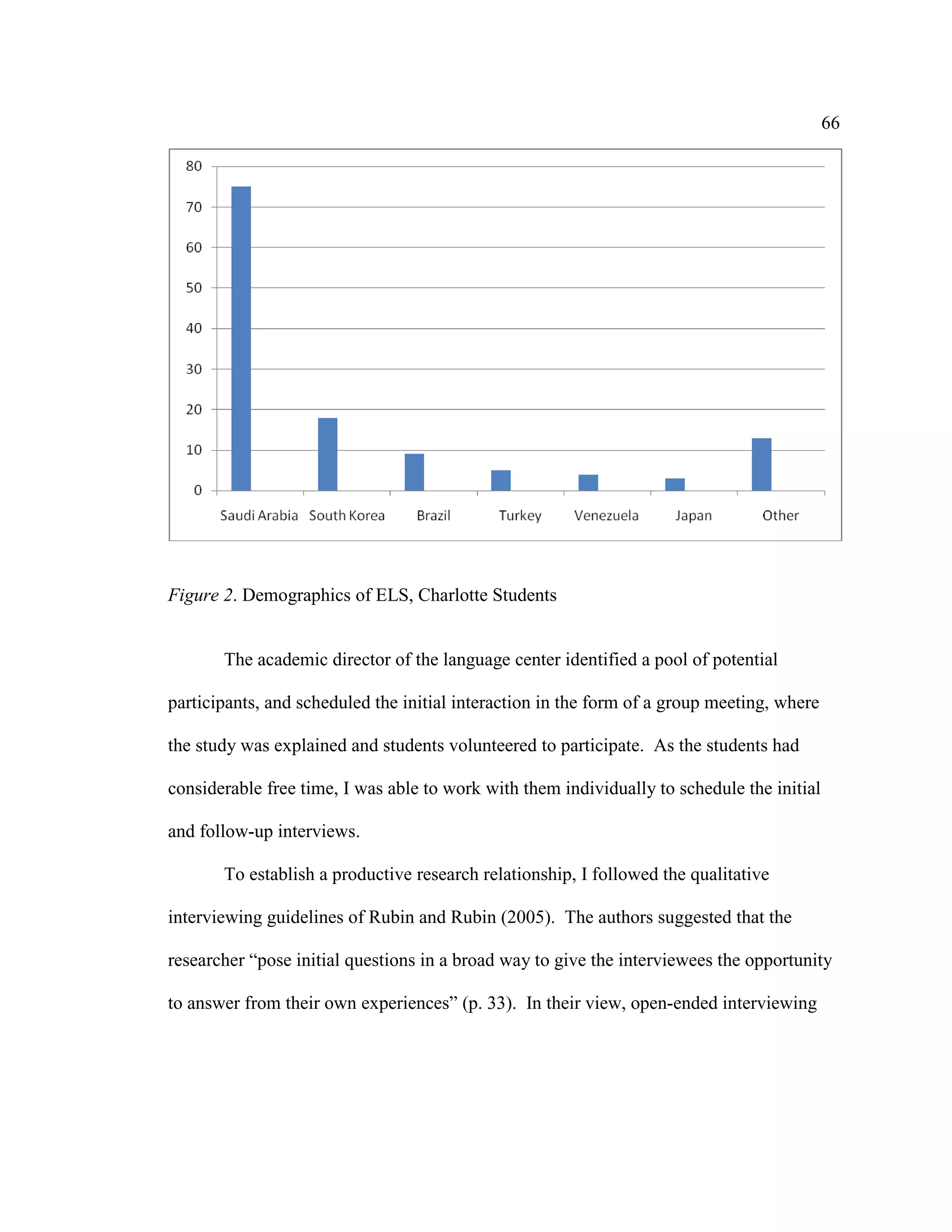

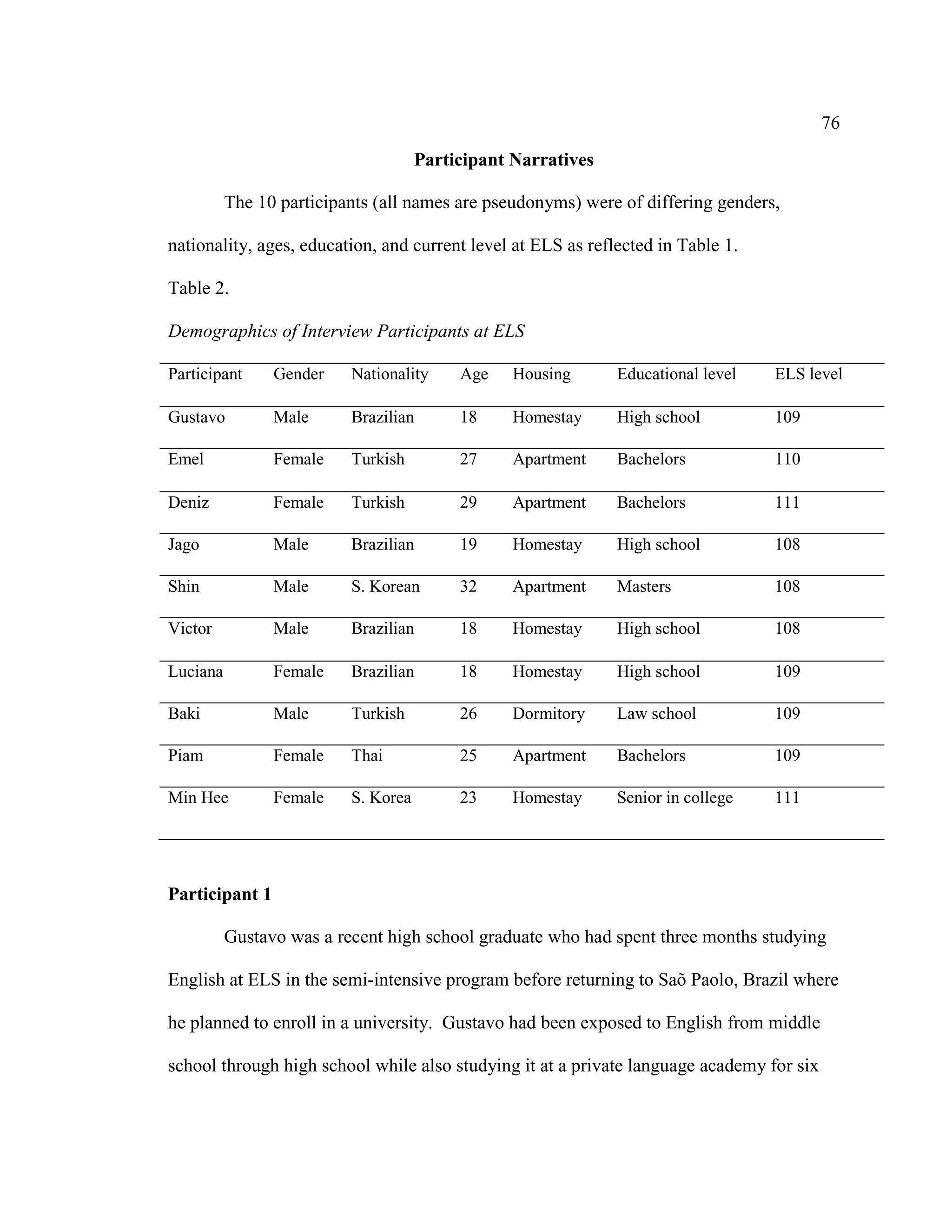

This dissertation examined language learning that occurs outside the classroom for English language students. The author conducted interviews with 10 students at an English language school in the southeastern United States. The interviews explored the students' experiences using English outside of class time and their beliefs about how this affected their language learning. The findings showed that having additional free time did not automatically enhance language learning. Whether language was learned depended on the living arrangements students chose and their engagement with native English speakers. Students who lived with host families perceived their language learning to be most successful. Homestay accommodations emerged as the best option for language learning outside the classroom. The study provides insights to help students, teachers, and schools maximize opportunities for out-of-classroom English practice