The document summarizes the history and development of Mughal and Persian gardens from the 15th century Timurid period through the peak of the Mughal Empire. Key points include:

- Timur established the city of Samarkand as his capital in the 15th century, rebuilding it as a cultural center with lush gardens along a central water axis, establishing a prototype for later Islamic gardens.

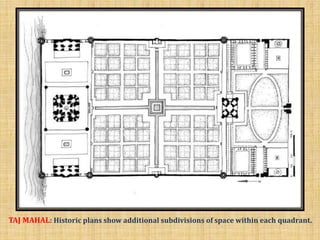

- This four-square garden design with a central pavilion, known as chahar-bagh, became symbolic of paradise and was influential on later Mughal gardens.

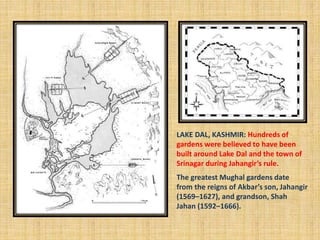

- The Mughals adopted Persian garden styles after founding their empire in India in the 16th century, adapting designs to varied