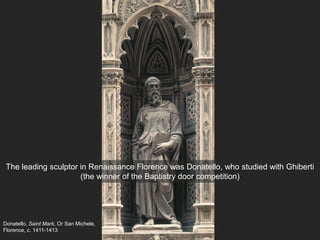

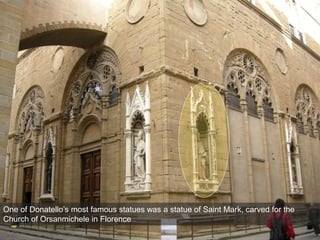

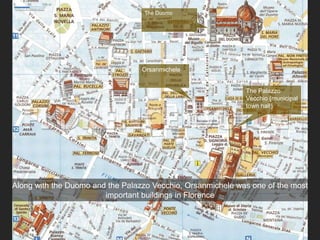

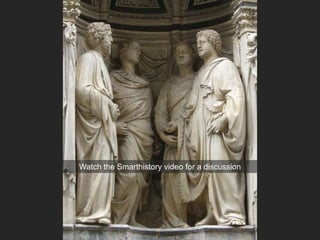

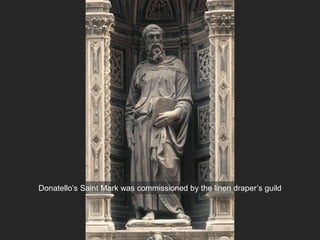

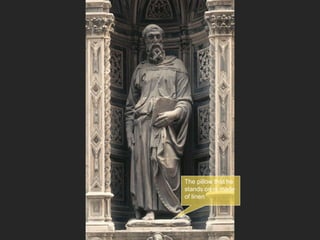

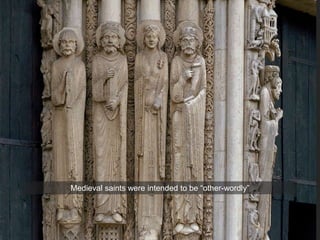

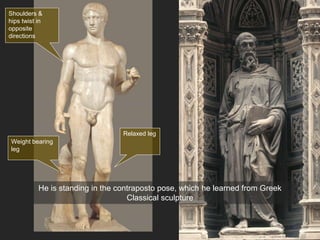

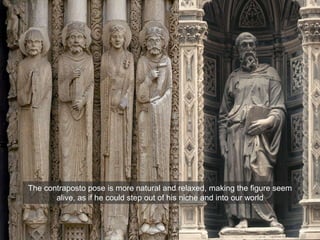

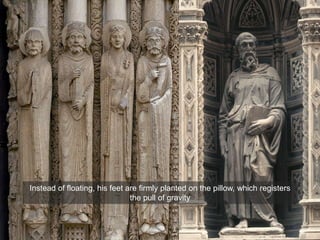

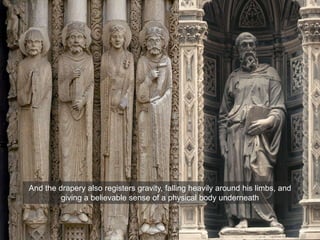

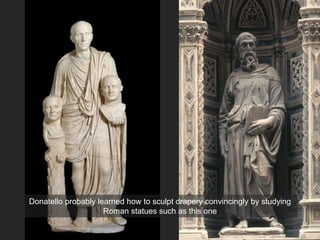

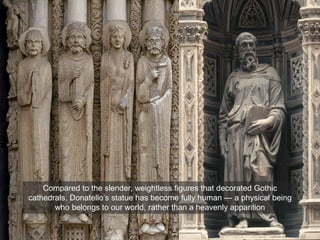

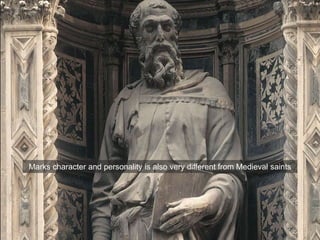

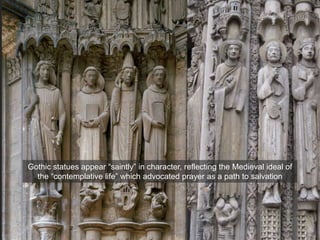

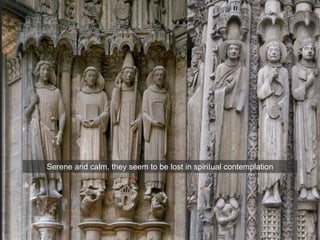

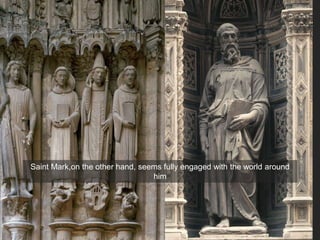

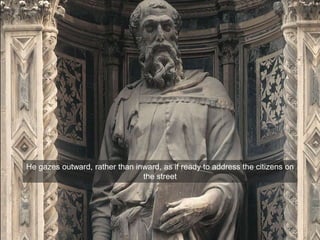

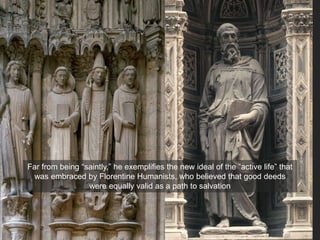

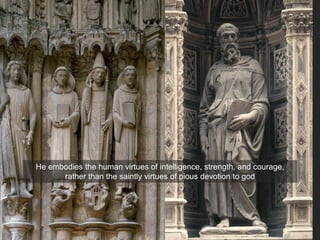

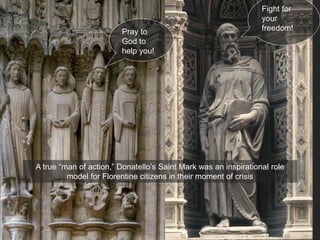

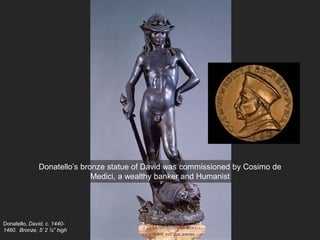

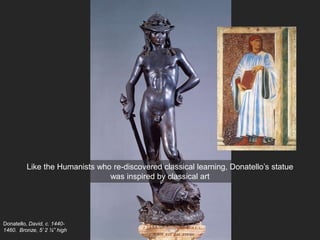

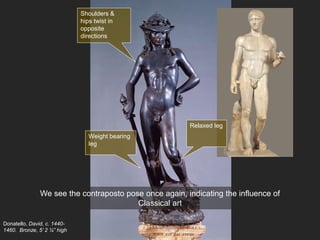

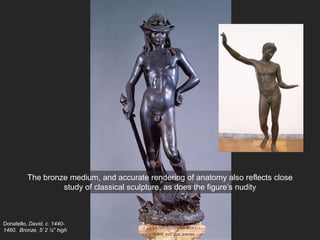

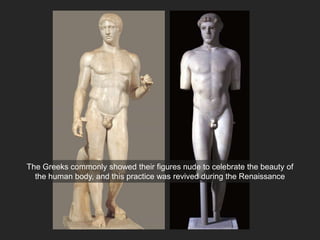

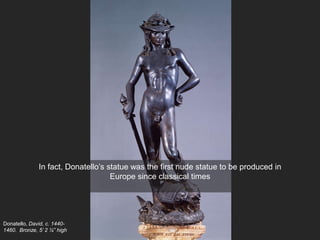

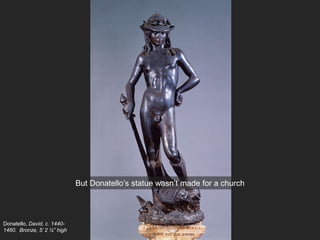

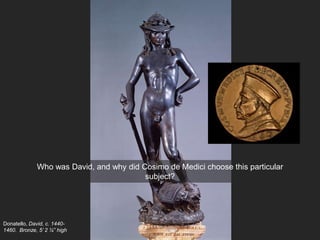

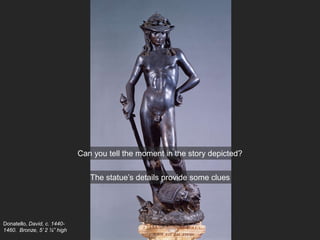

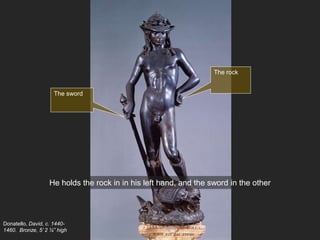

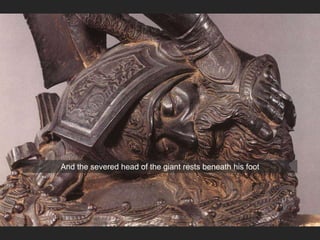

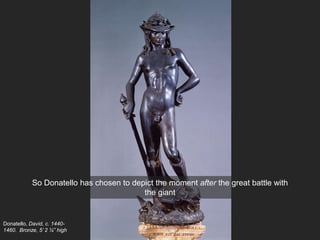

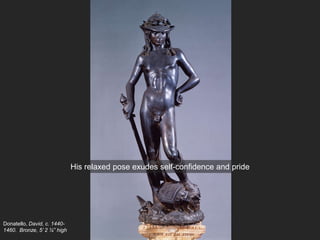

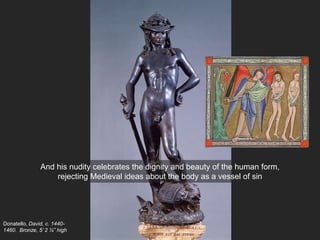

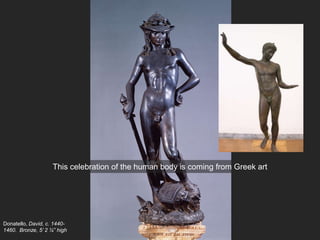

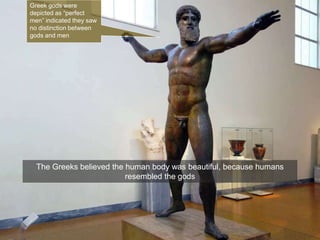

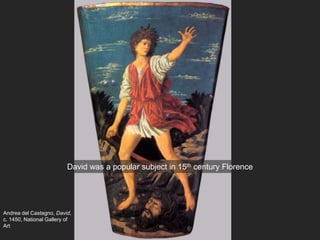

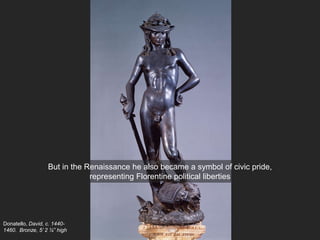

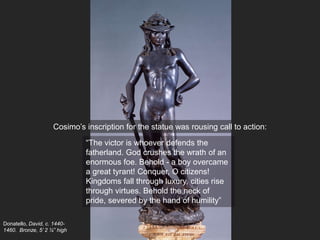

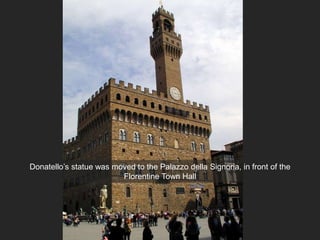

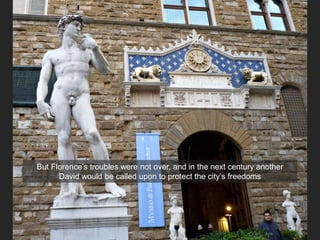

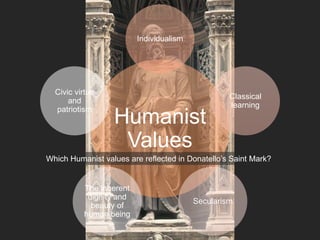

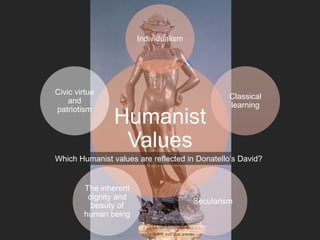

Donatello was a leading Renaissance sculptor in Florence who drew inspiration from classical antiquity. His statue of Saint Mark for the city's Orsanmichele church marked a radical departure from medieval representations of saints. Depicting Saint Mark in a natural, weight-bearing pose and engaged with the world, it embodied the humanist ideals of civic virtue and the dignity of man. Donatello's later bronze David, commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici, celebrated the human body and human potential through its contrapposto pose and nudity inspired by classical Greek art. It became a symbol of Florence's civic pride and liberties.