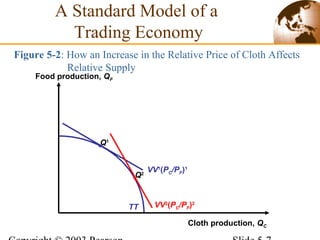

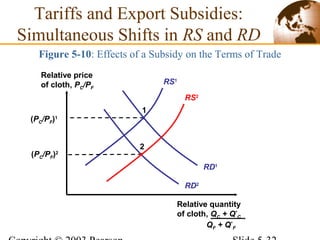

This document provides an overview of the standard trade model. It discusses key concepts like production possibility frontiers, relative supply and demand curves, and terms of trade. Countries produce two goods and their production depends on relative prices. World trade equilibrium occurs at the intersection of global relative supply and demand. Economic growth can shift supply curves, impacting terms of trade. International transfers can also shift demand curves and influence prices. Tariffs simultaneously impact both relative supply and demand.