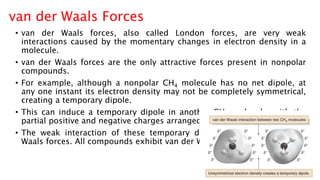

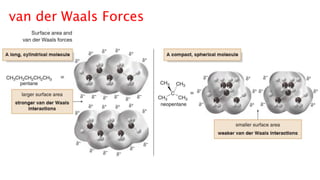

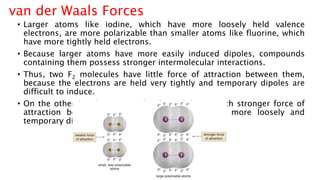

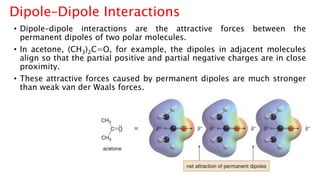

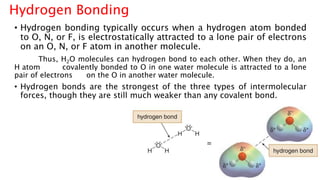

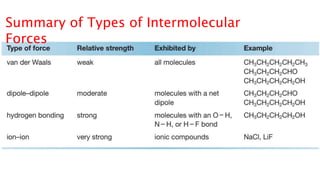

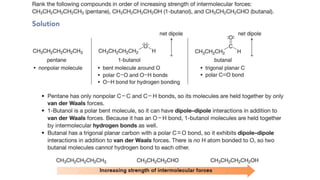

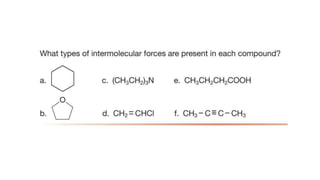

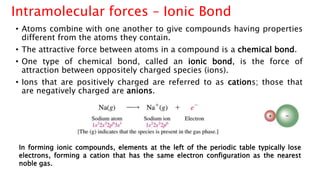

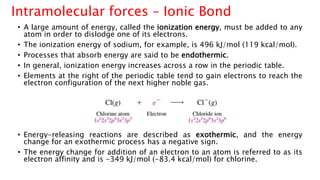

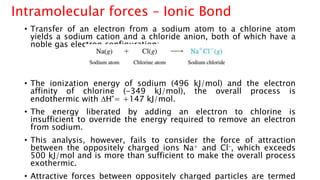

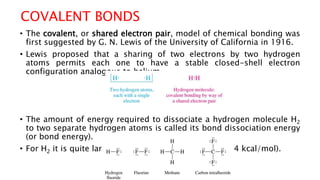

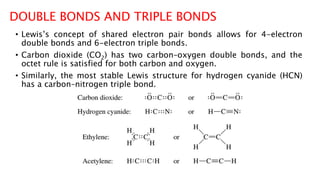

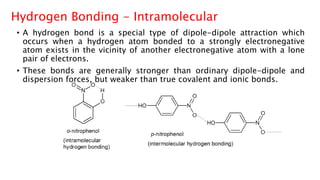

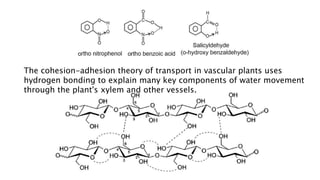

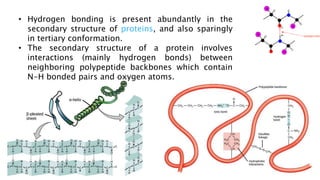

The document discusses different types of intramolecular and intermolecular forces. It describes ionic bonds as the strong electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions. Covalent bonds are described as the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. It also discusses hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, and van der Waals forces as different types of intermolecular forces that are weaker than ionic or covalent bonds.