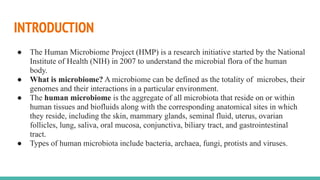

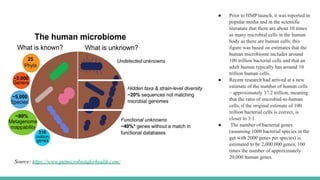

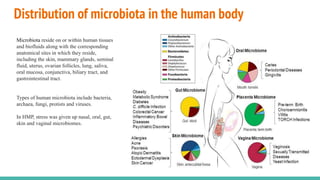

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) is a National Institutes of Health initiative launched in 2007 to explore the microbial flora of the human body and its influence on health. It has produced extensive datasets and established the link between microbiota, disease susceptibility, and therapeutic responses. The project has now evolved into its second phase, aiming for a comprehensive understanding of the microbiome's role in health and disease through innovative research methodologies.