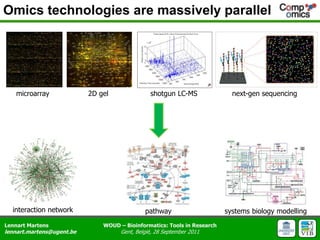

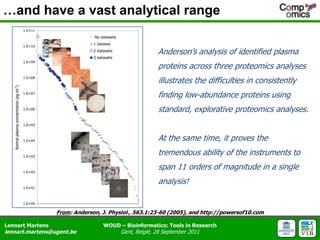

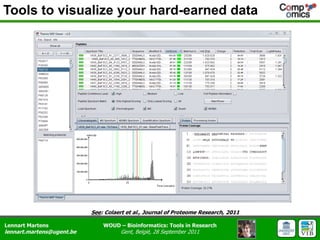

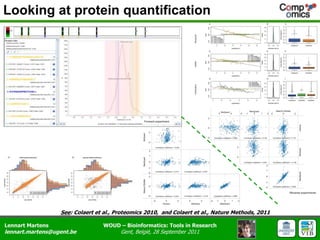

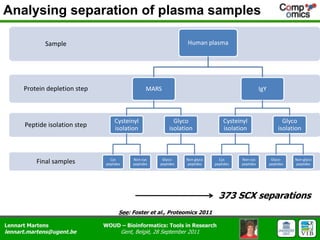

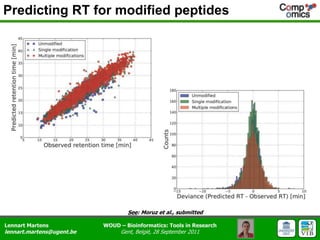

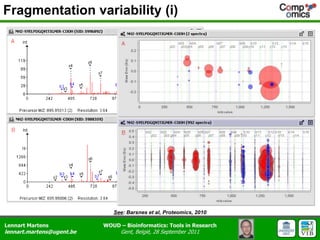

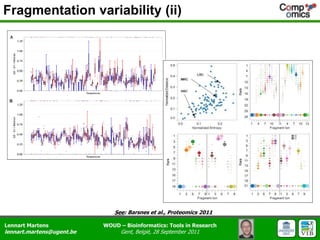

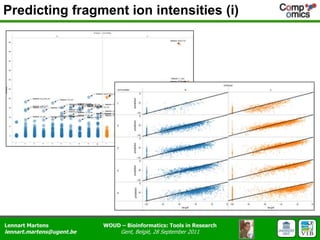

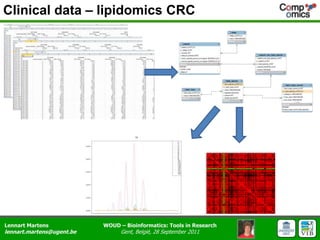

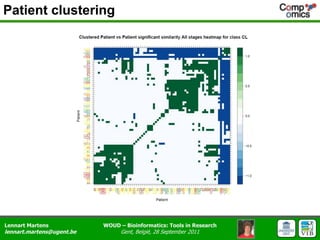

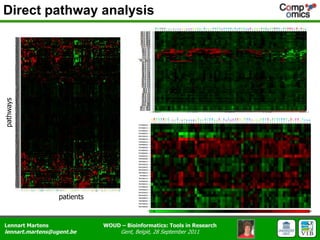

The document discusses the capabilities and challenges of proteomics technologies in clinical research, emphasizing the difficulty of consistently detecting low-abundance proteins despite powerful analytical methods. It references various studies and tools for analyzing and visualizing proteomics data and highlights the integration of omics data for clinical application. Acknowledgments are given to collaborators and funding sources in the field.