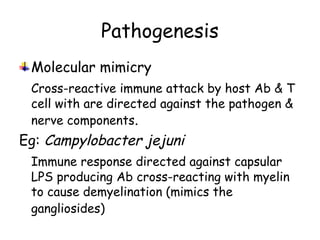

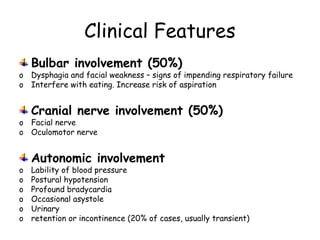

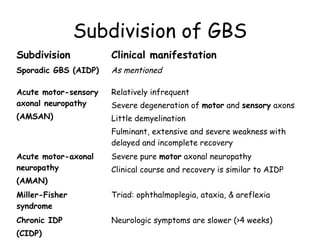

Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) is a post-infectious polyneuropathy that affects the peripheral nervous system. It most commonly develops following a gastrointestinal or respiratory infection. The syndrome involves demyelination of the nerves leading to progressive muscle weakness starting in the lower limbs and sometimes involving cranial nerves and autonomic dysfunction. Diagnosis is based on clinical features and supportive test findings such as elevated CSF protein and nerve conduction studies. Treatment involves supportive care and immunomodulating therapies like intravenous immunoglobulin which aid recovery beginning within a few weeks in most cases. Prognosis is generally good but respiratory or bulbar involvement can be life threatening if not properly managed.