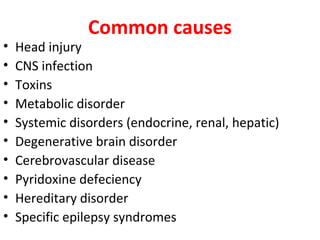

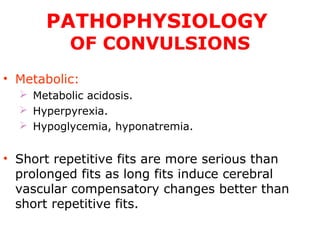

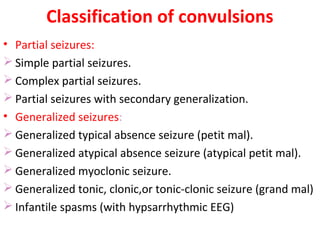

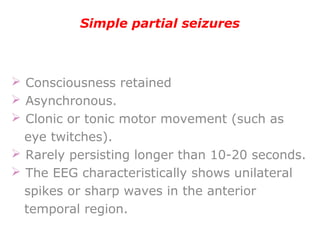

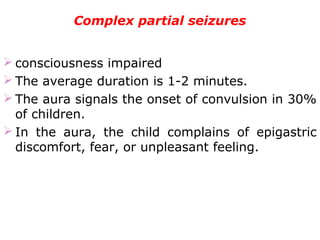

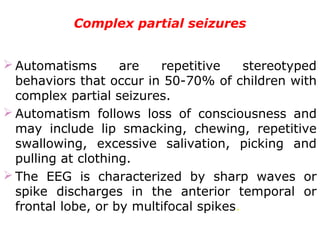

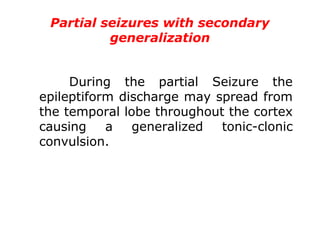

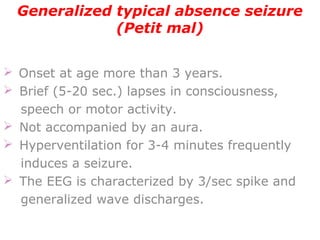

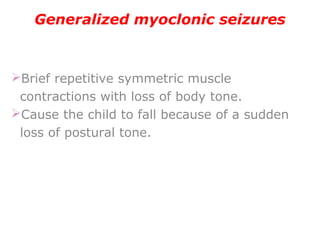

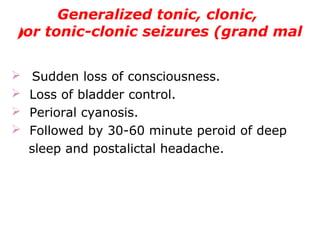

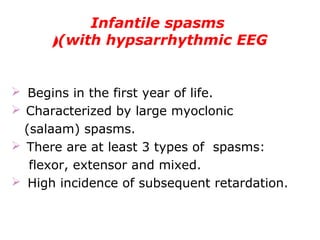

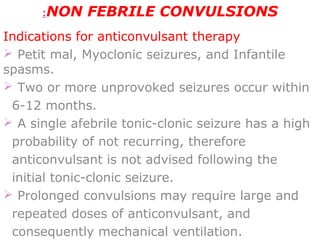

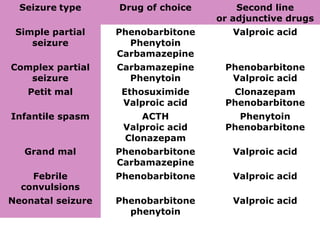

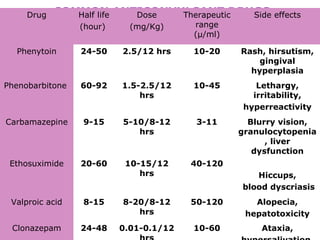

1. The document discusses convulsions (seizures) in children, including their causes, types, diagnosis, and treatment. It describes different types of seizures like simple partial, complex partial, generalized absence, myoclonic, tonic-clonic, and infantile spasms.

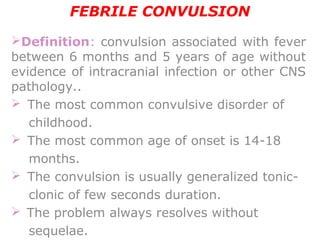

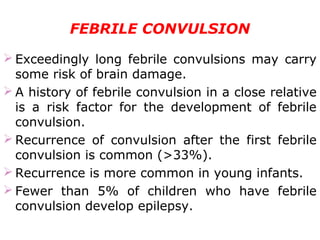

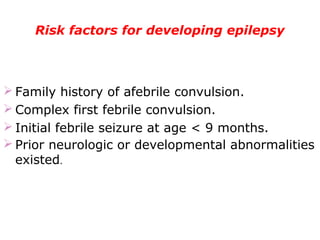

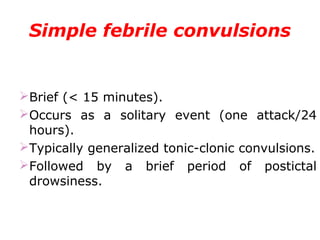

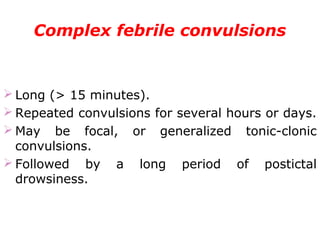

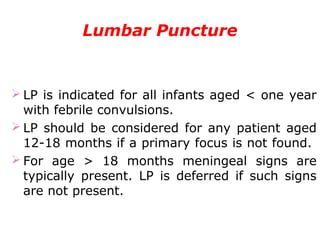

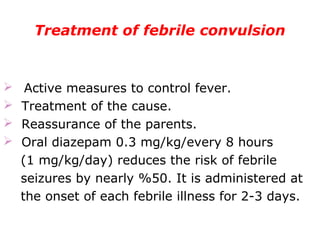

2. Febrile seizures, which occur due to fever but are not indicative of epilepsy, are also explained. Risk factors for developing epilepsy after febrile seizures are provided.

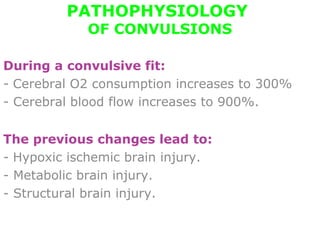

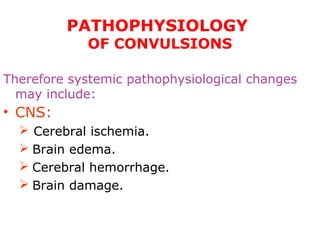

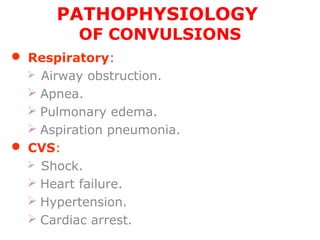

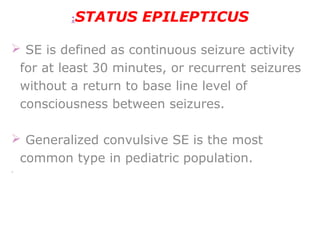

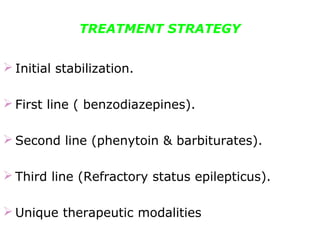

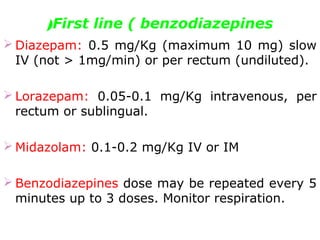

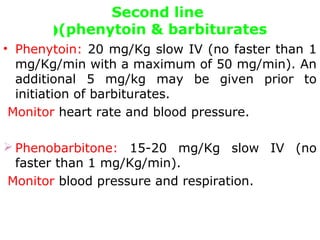

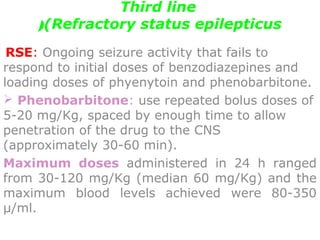

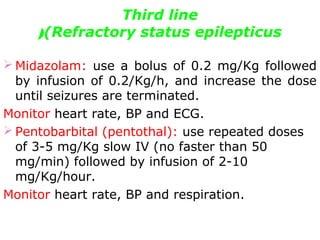

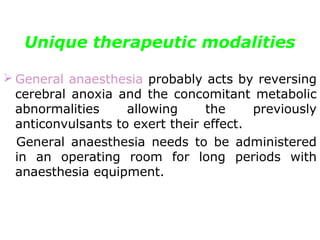

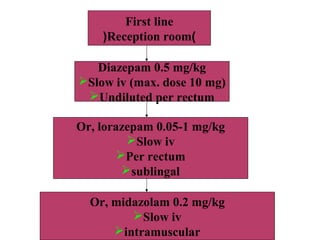

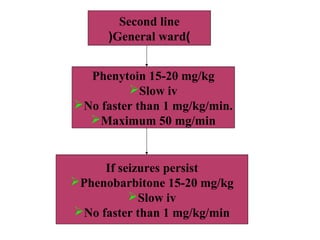

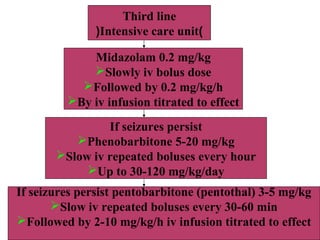

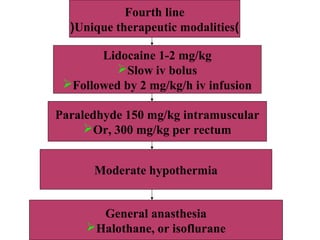

3. Status epilepticus, defined as continuous seizure activity for over 30 minutes, is outlined as a medical emergency with potential for neurological injury and mortality. Treatment options for different seizure types and status epilepticus are summarized.