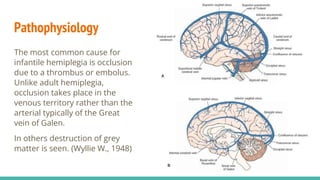

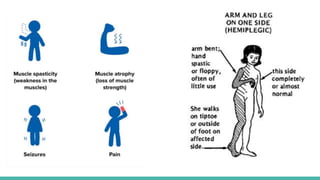

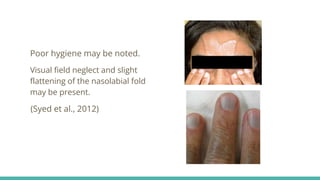

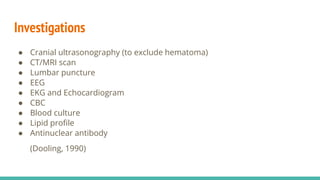

Infantile hemiplegia is a sudden onset form of hemiplegia in children aged a few weeks to over six years, often caused by thrombus or embolus occlusion. Clinical manifestations include weakness, spasticity, seizures, and cognitive impairments, with assessment involving history, examination, and various investigations. Management includes medical and surgical treatments, physiotherapy, and recent advances in therapeutic techniques aimed at restoring function.