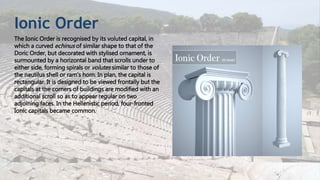

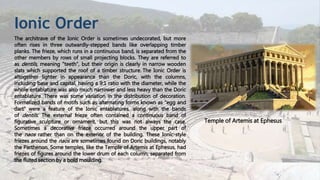

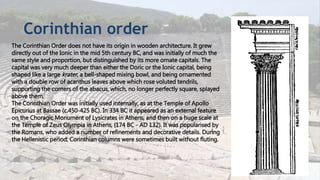

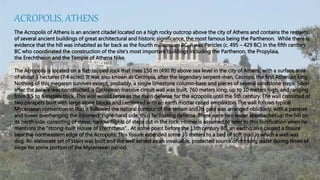

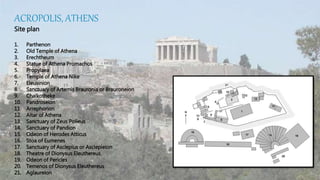

Ancient Greek architecture emerged around 900 BC and is characterized by temples, open-air theaters, and other public structures, with notable innovations in design and construction techniques. Key architectural styles include the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, each defined by unique column designs and entablatures. The Parthenon is a prime example, symbolizing ancient Greece's architectural achievement and cultural significance, dedicated to the goddess Athena.