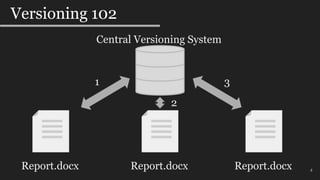

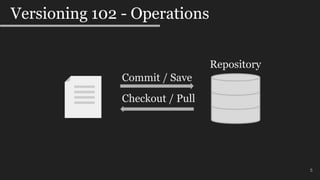

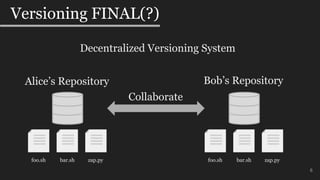

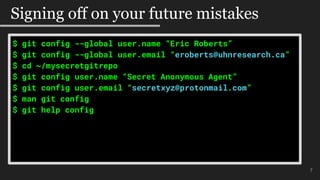

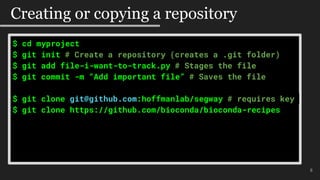

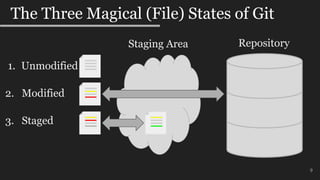

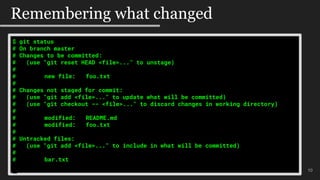

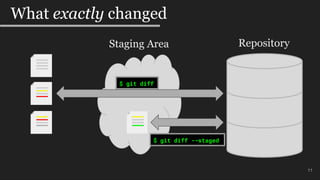

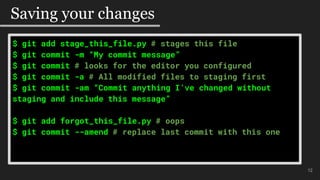

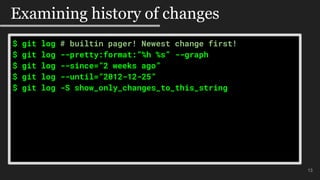

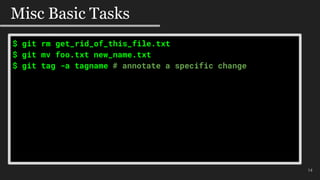

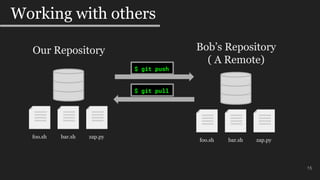

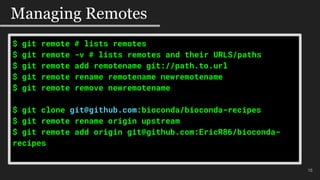

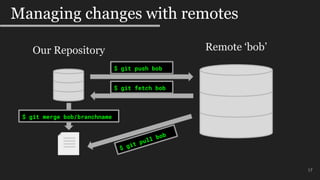

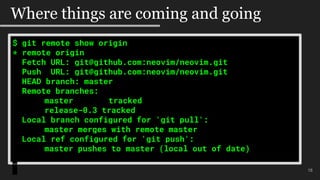

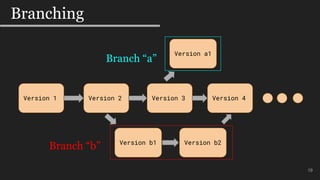

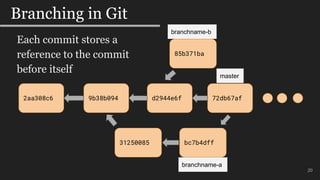

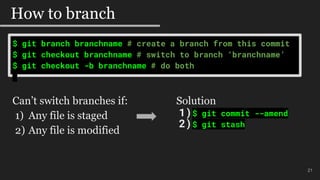

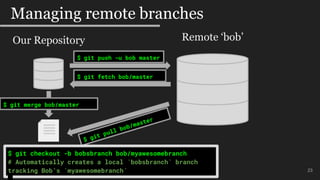

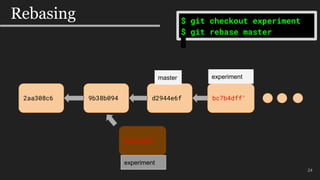

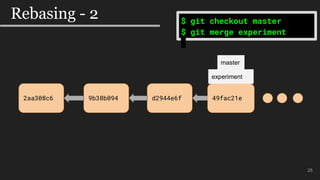

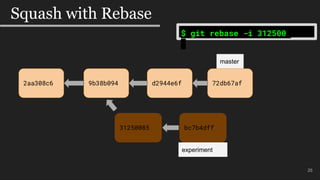

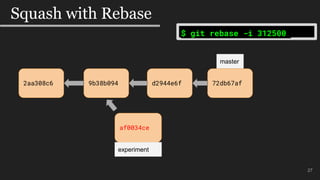

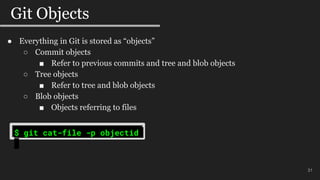

This document provides an overview and introduction to using the version control system Git. It covers basic Git concepts and operations including configuration, the three main states files can be in, committing changes, viewing history and logs, branching, merging, rebasing, tagging, and collaborating remotely. The document also discusses some internals of Git including how objects are stored and how Git and other version control systems originated.