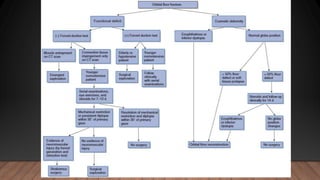

The document discusses various types of facial fractures including orbital, frontal sinus, and panfacial fractures. It provides details on:

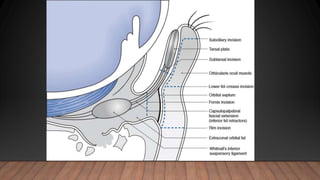

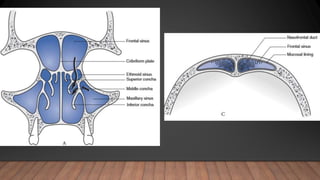

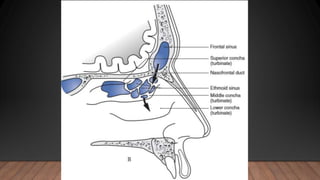

- The anatomy of the orbit and types of orbital wall fractures.

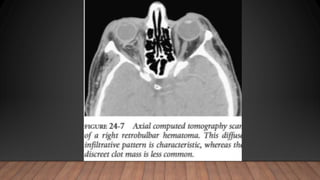

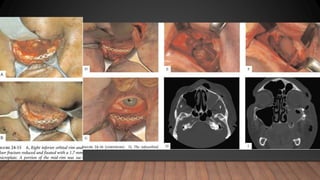

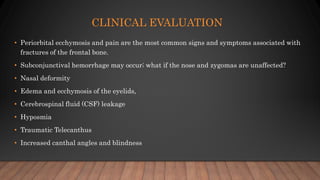

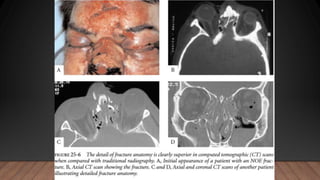

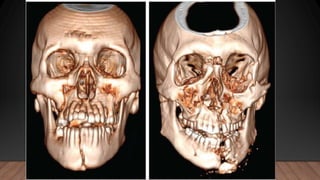

- Clinical evaluation including imaging techniques like CT scans.

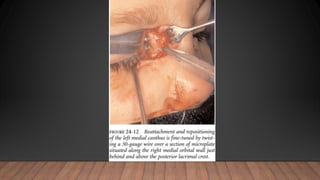

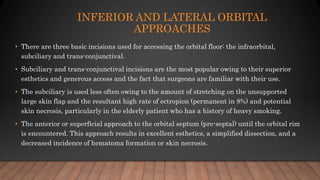

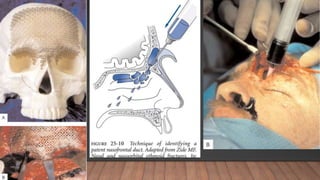

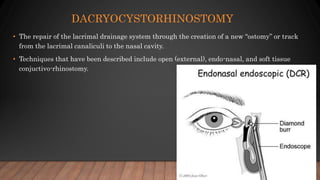

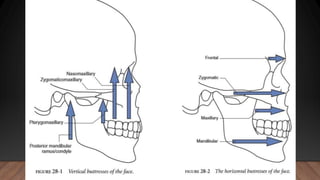

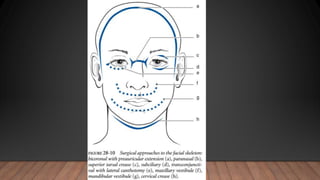

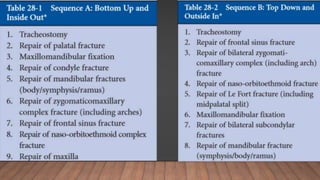

- Surgical management of fractures including approaches, reconstruction goals and materials used.

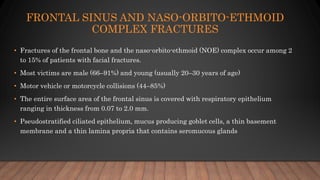

- Specific challenges with fractures of the frontal sinus and naso-orbito-ethmoid complex given the thin sinus lining and importance of coronal flap access.

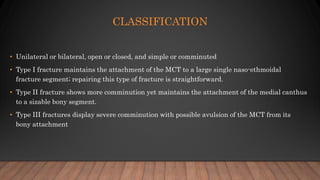

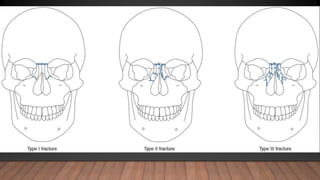

- Classification and reconstruction considerations for severe panfacial fractures involving multiple facial bones.