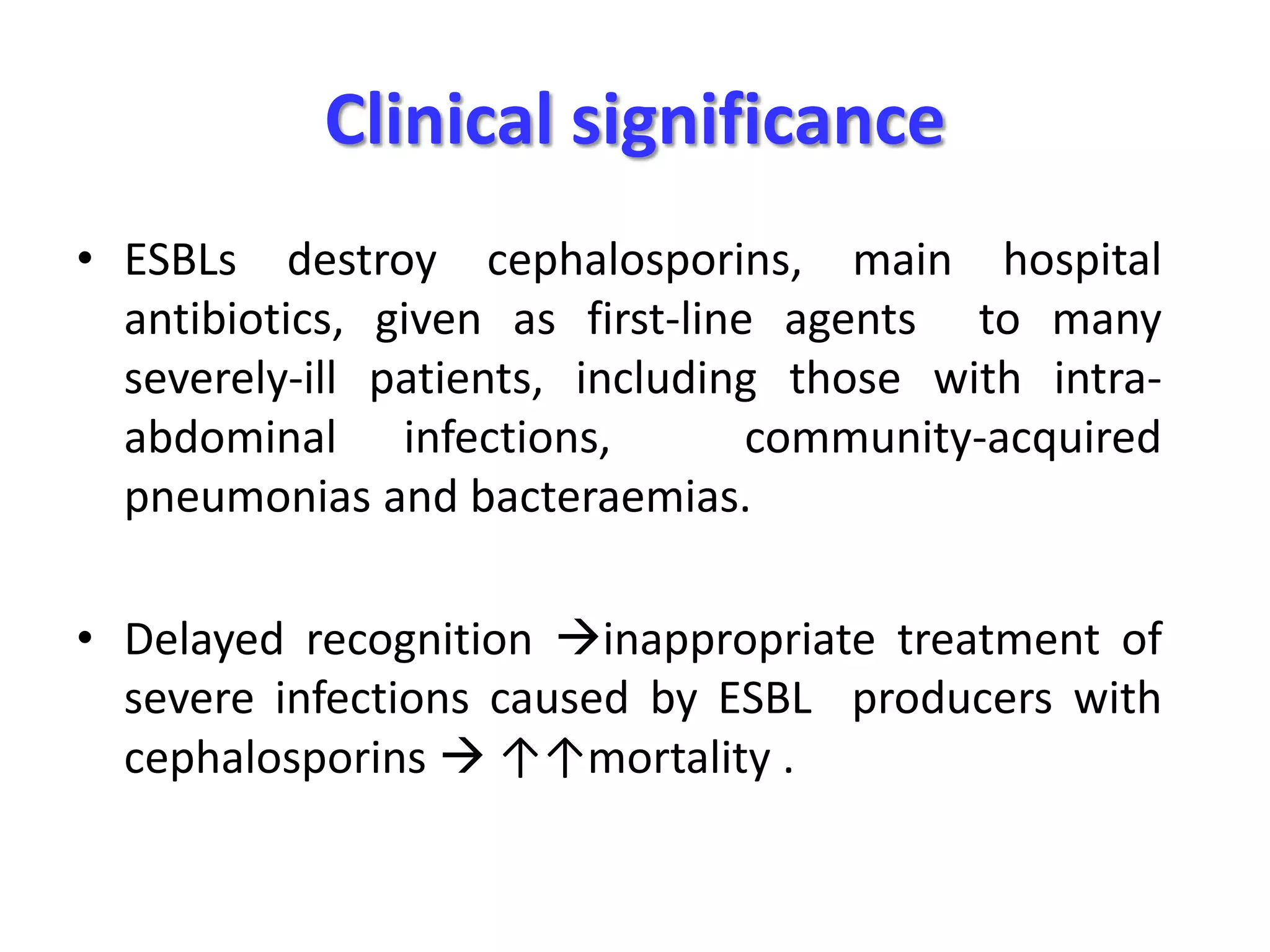

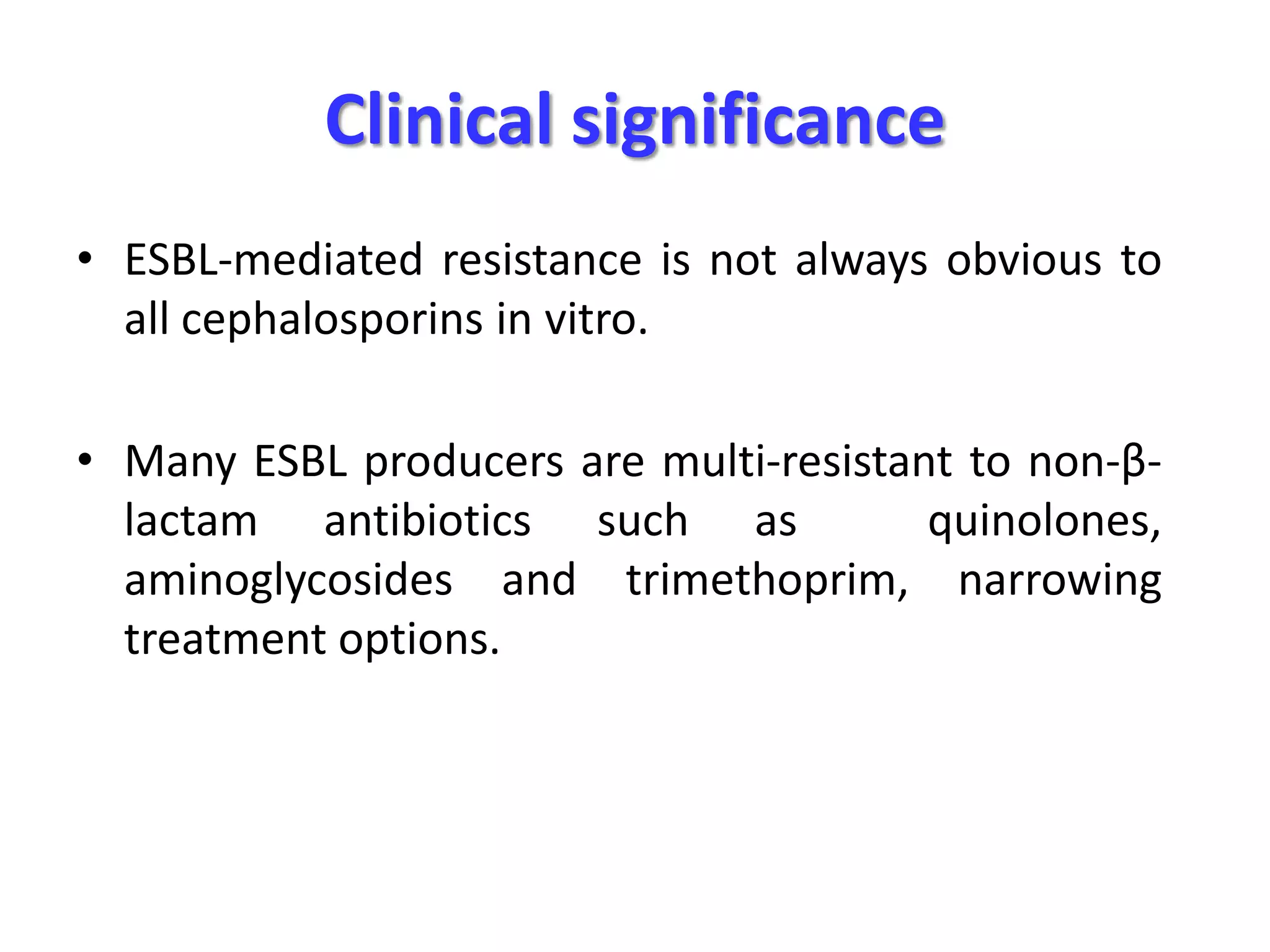

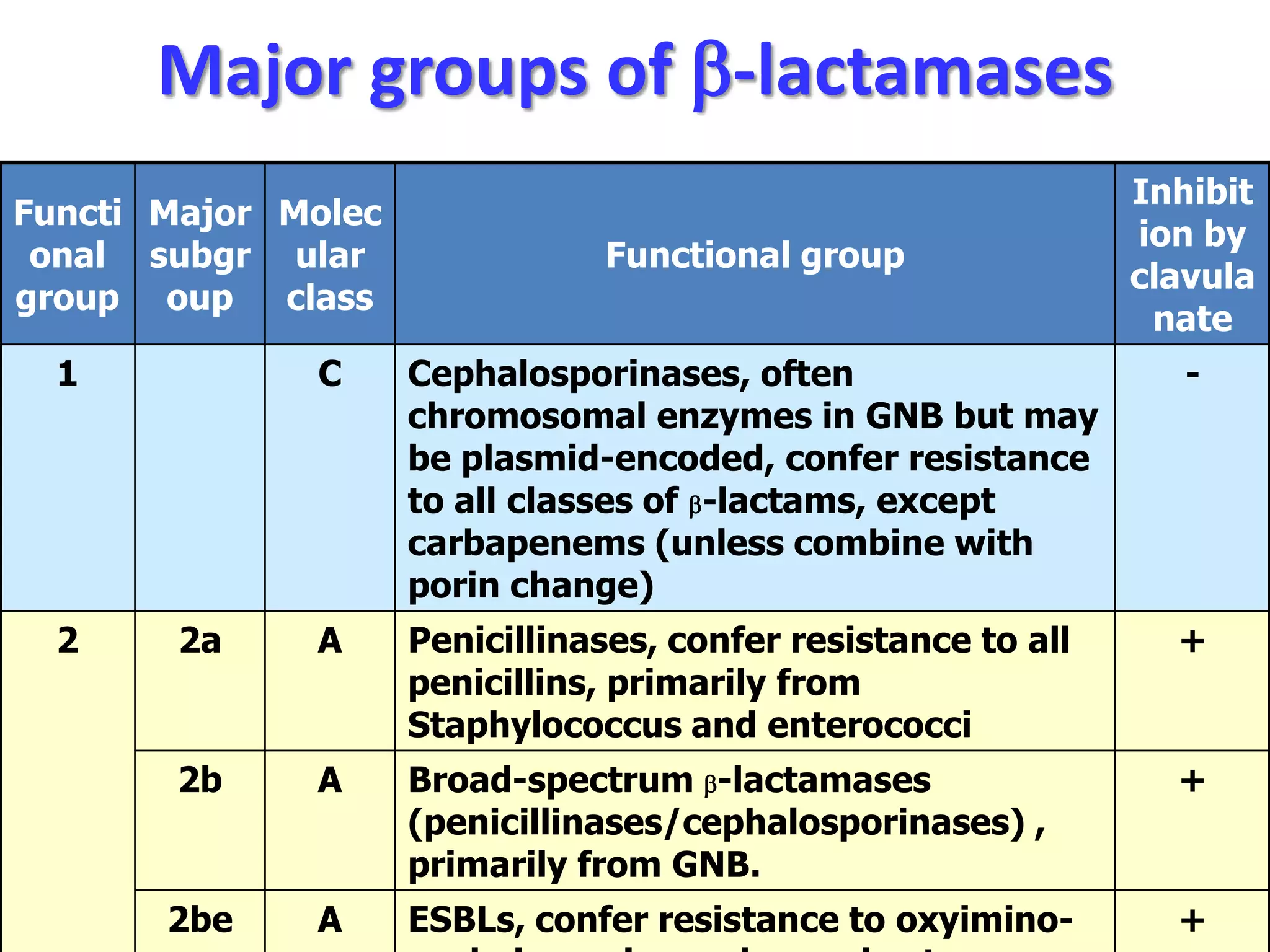

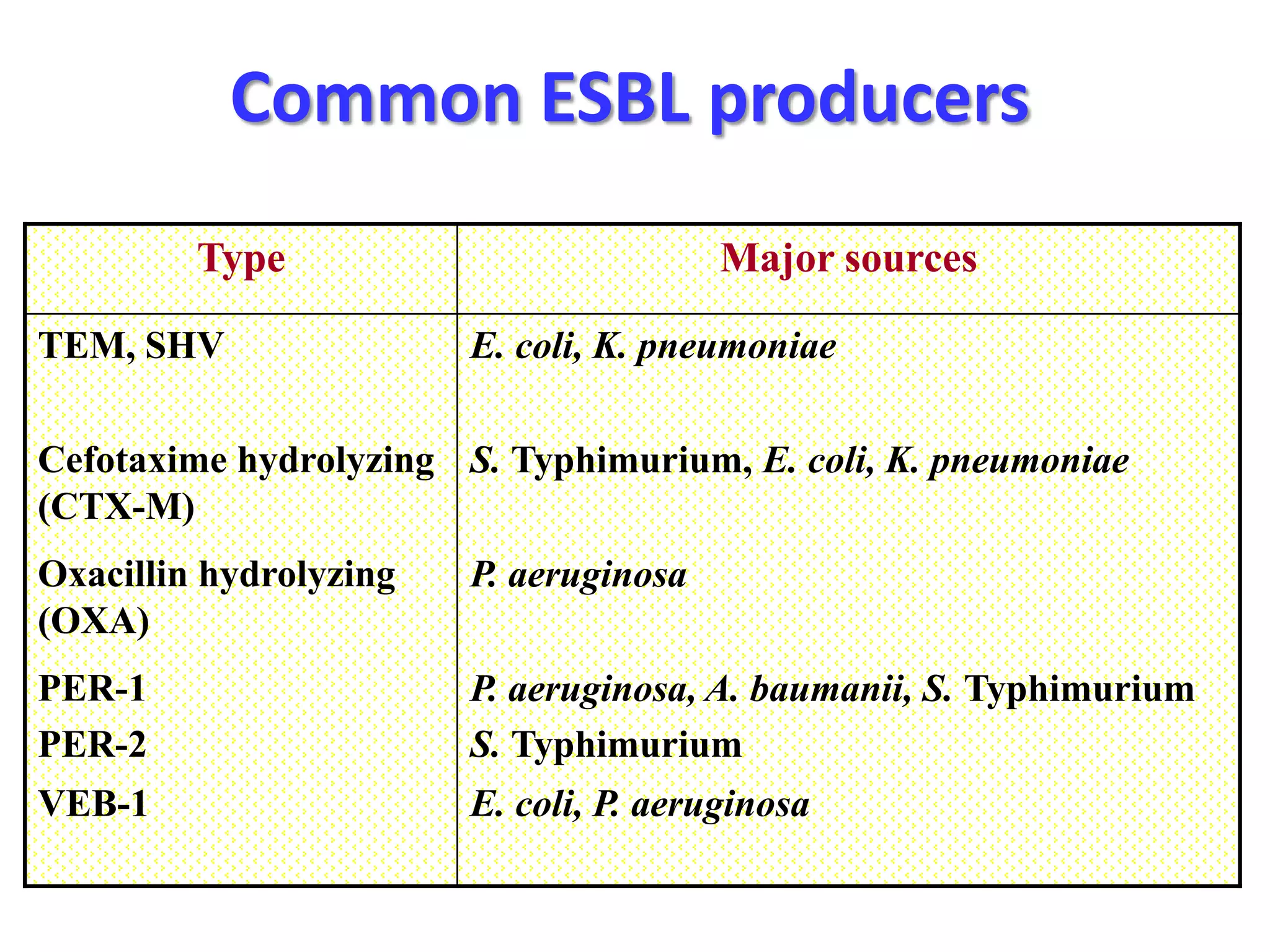

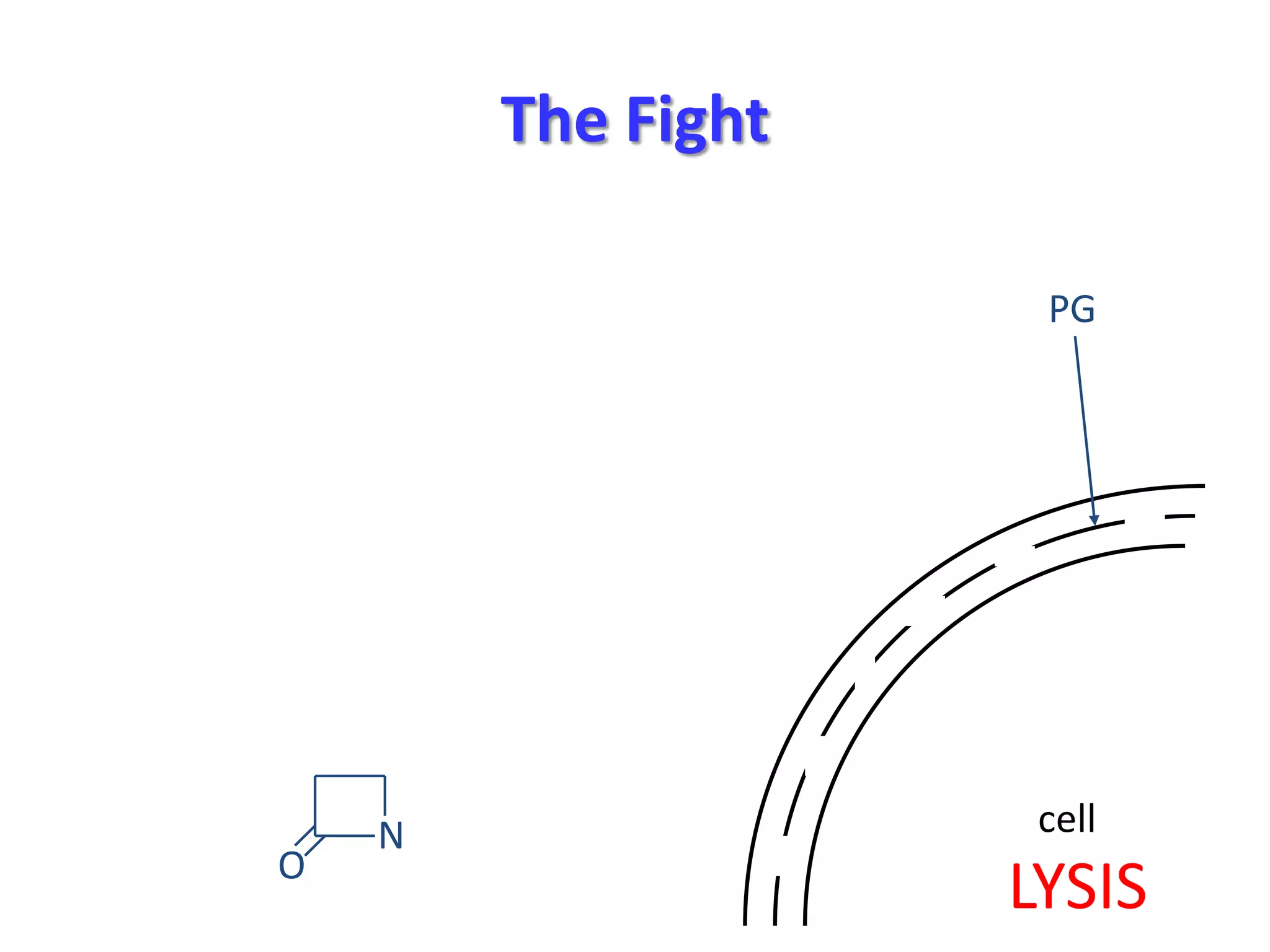

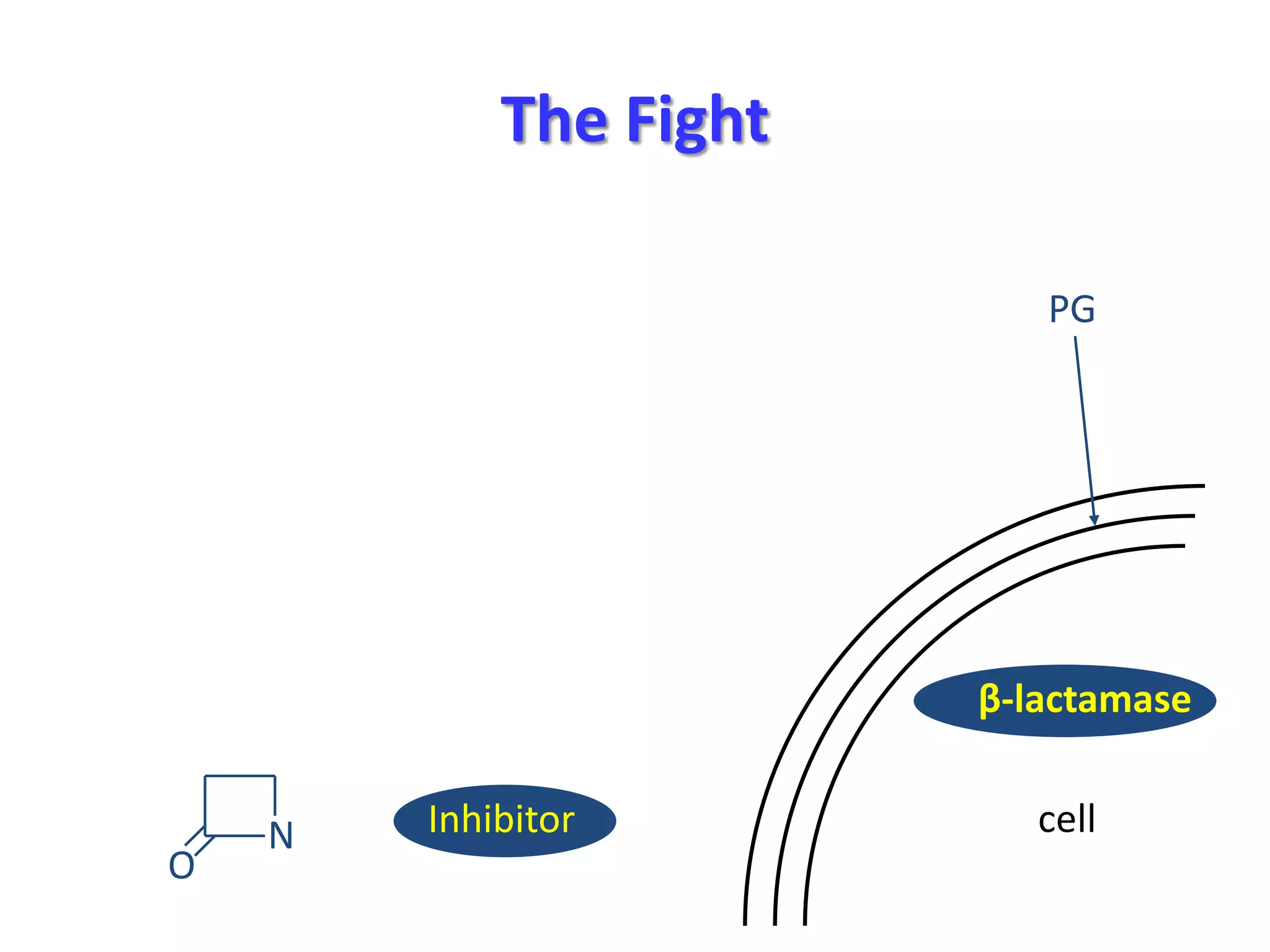

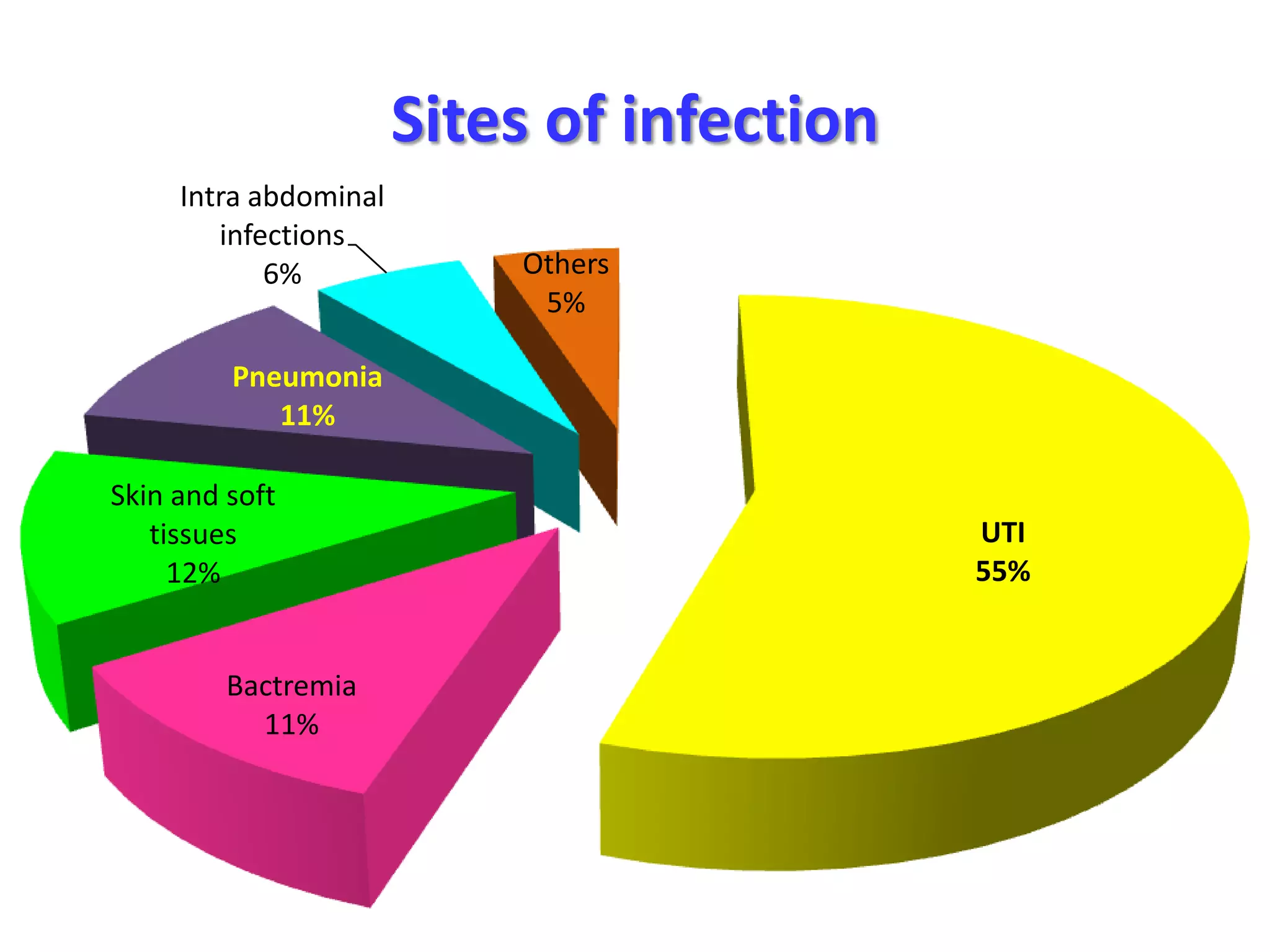

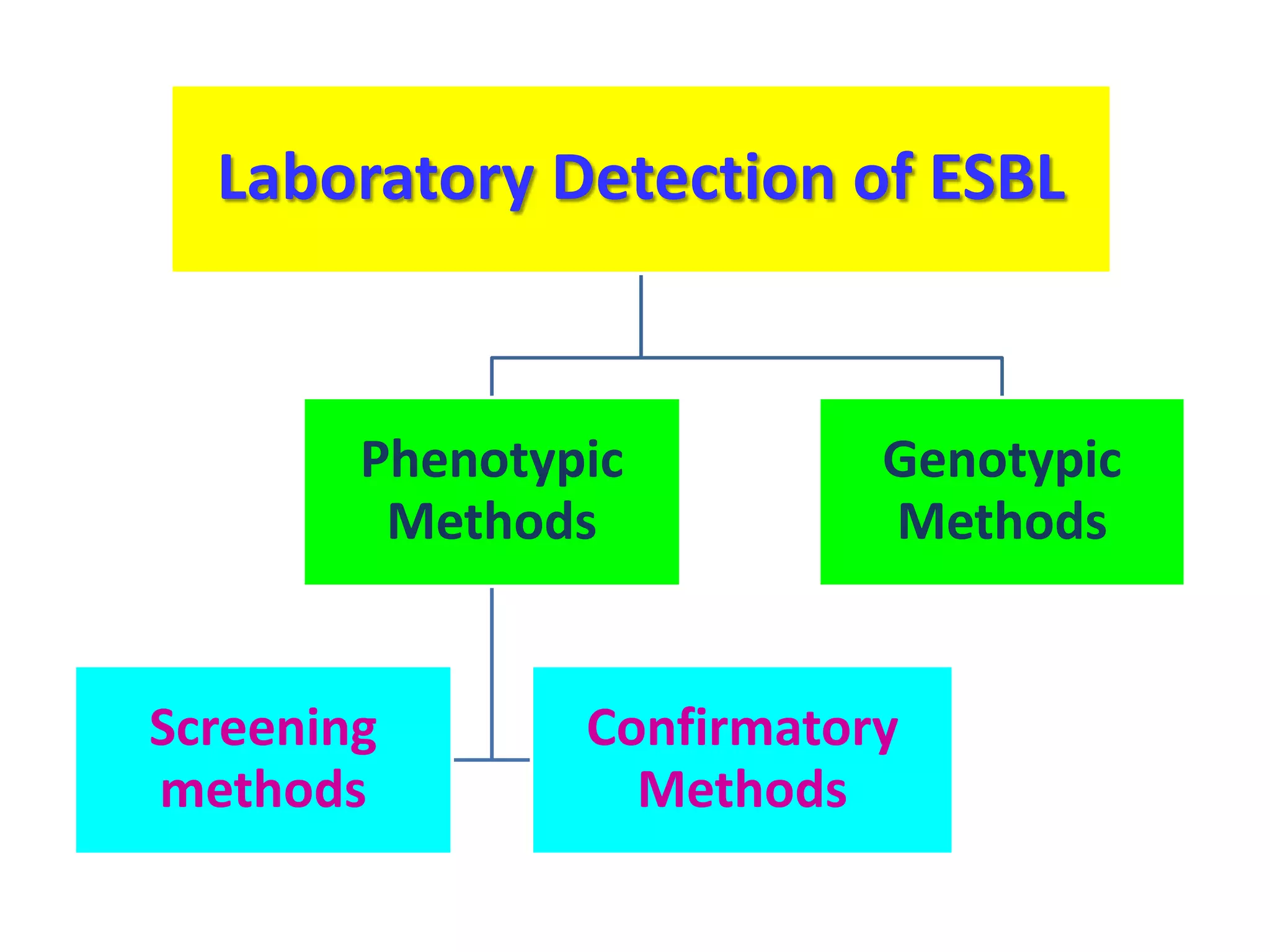

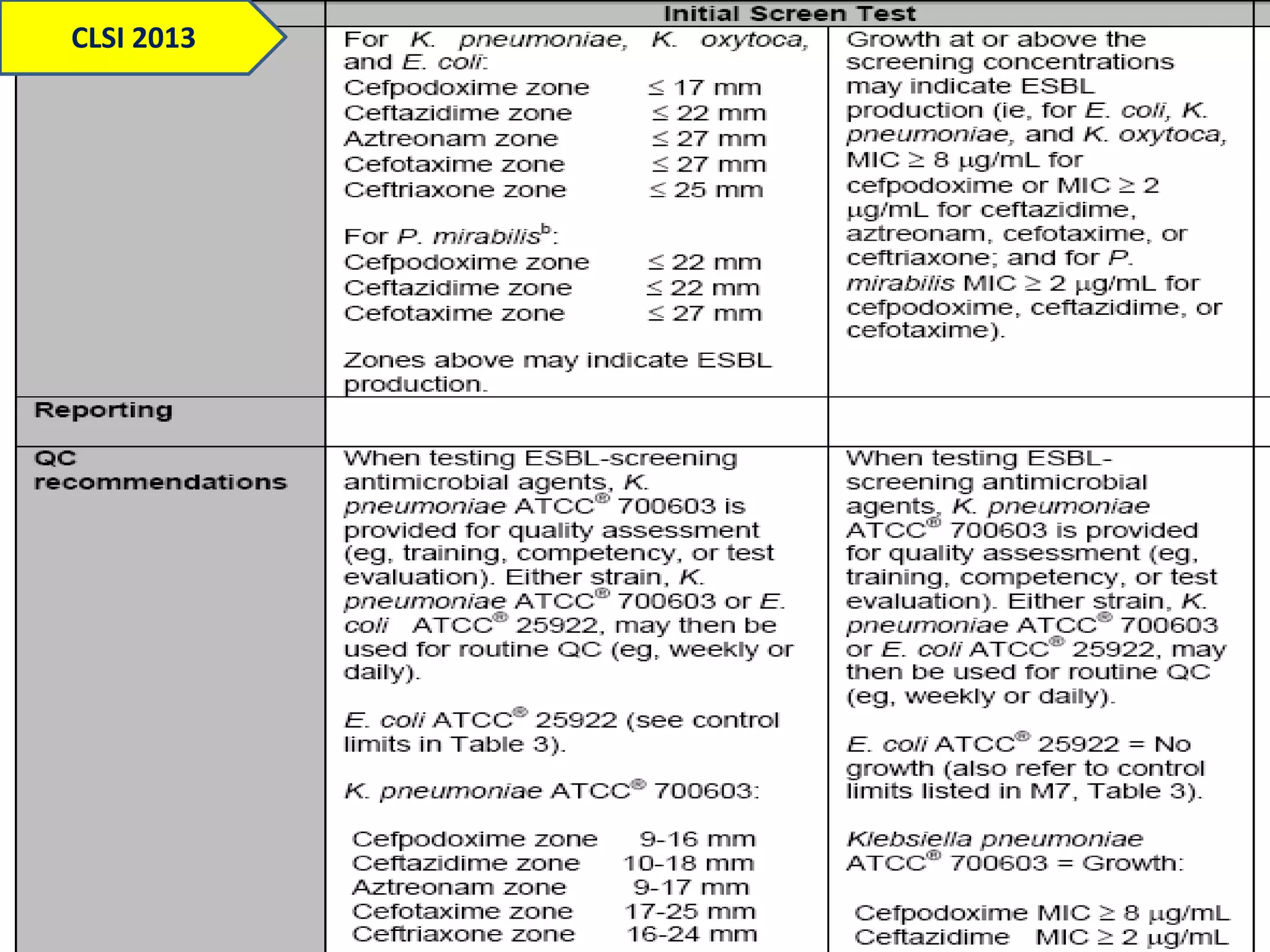

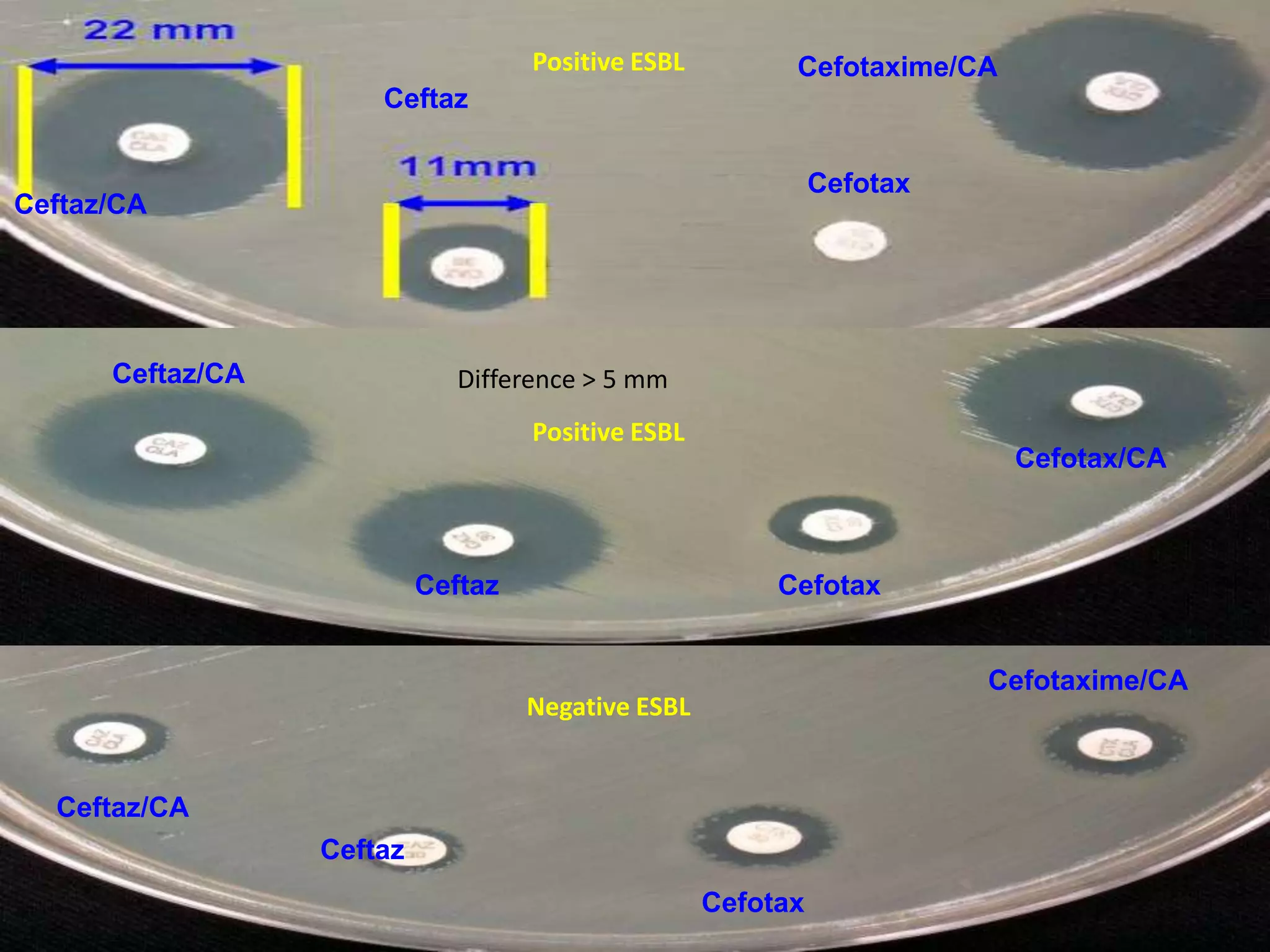

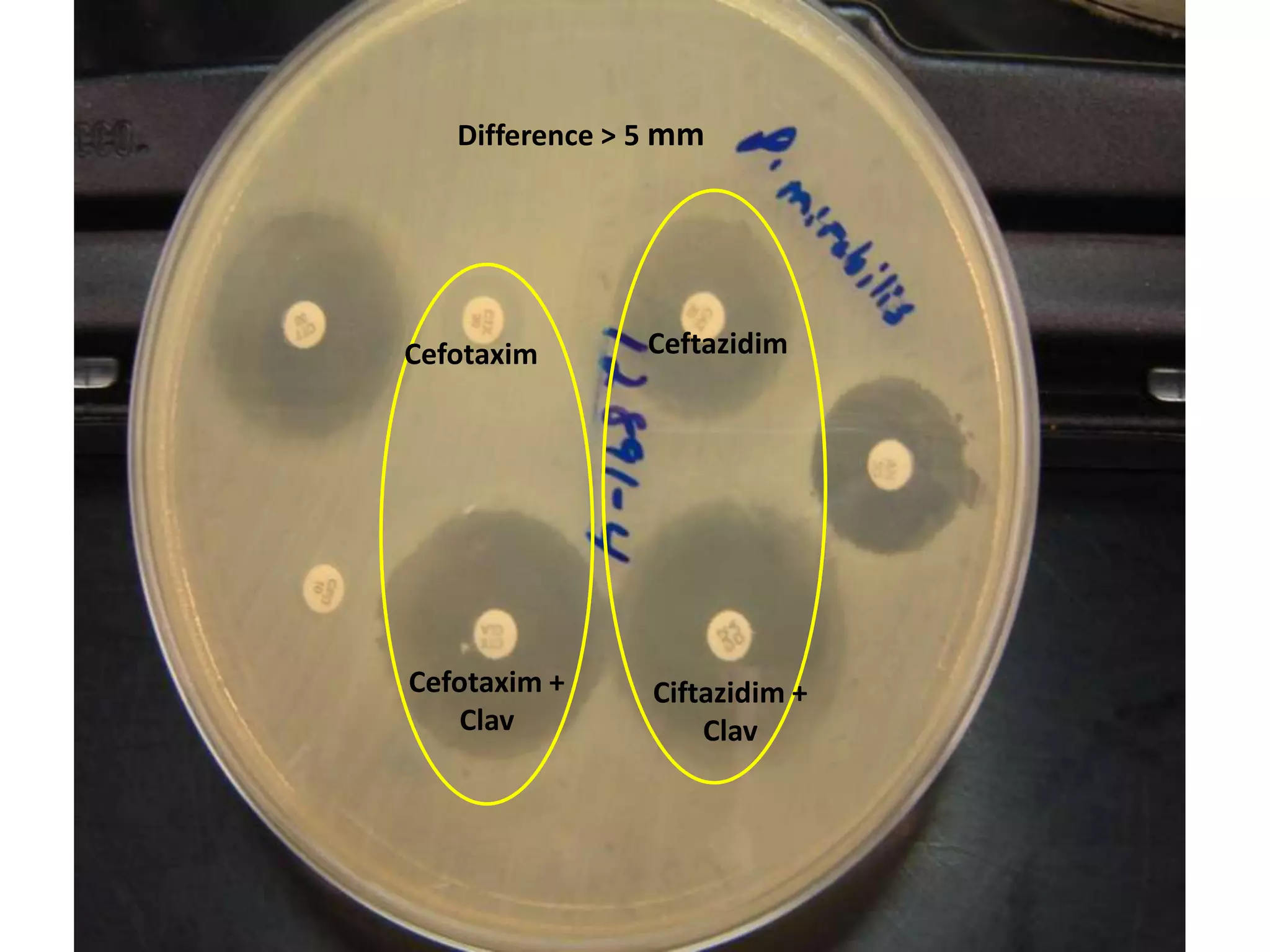

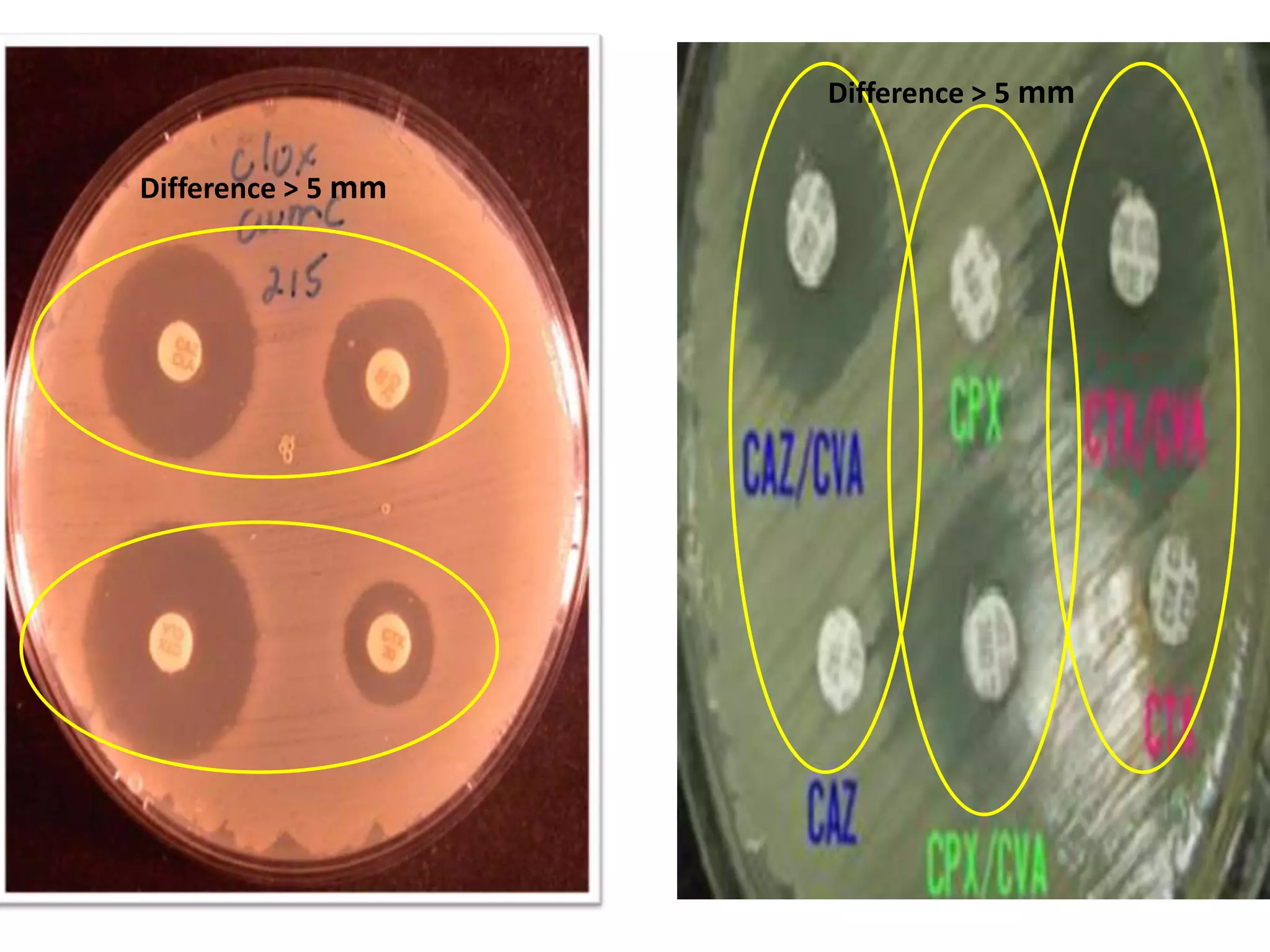

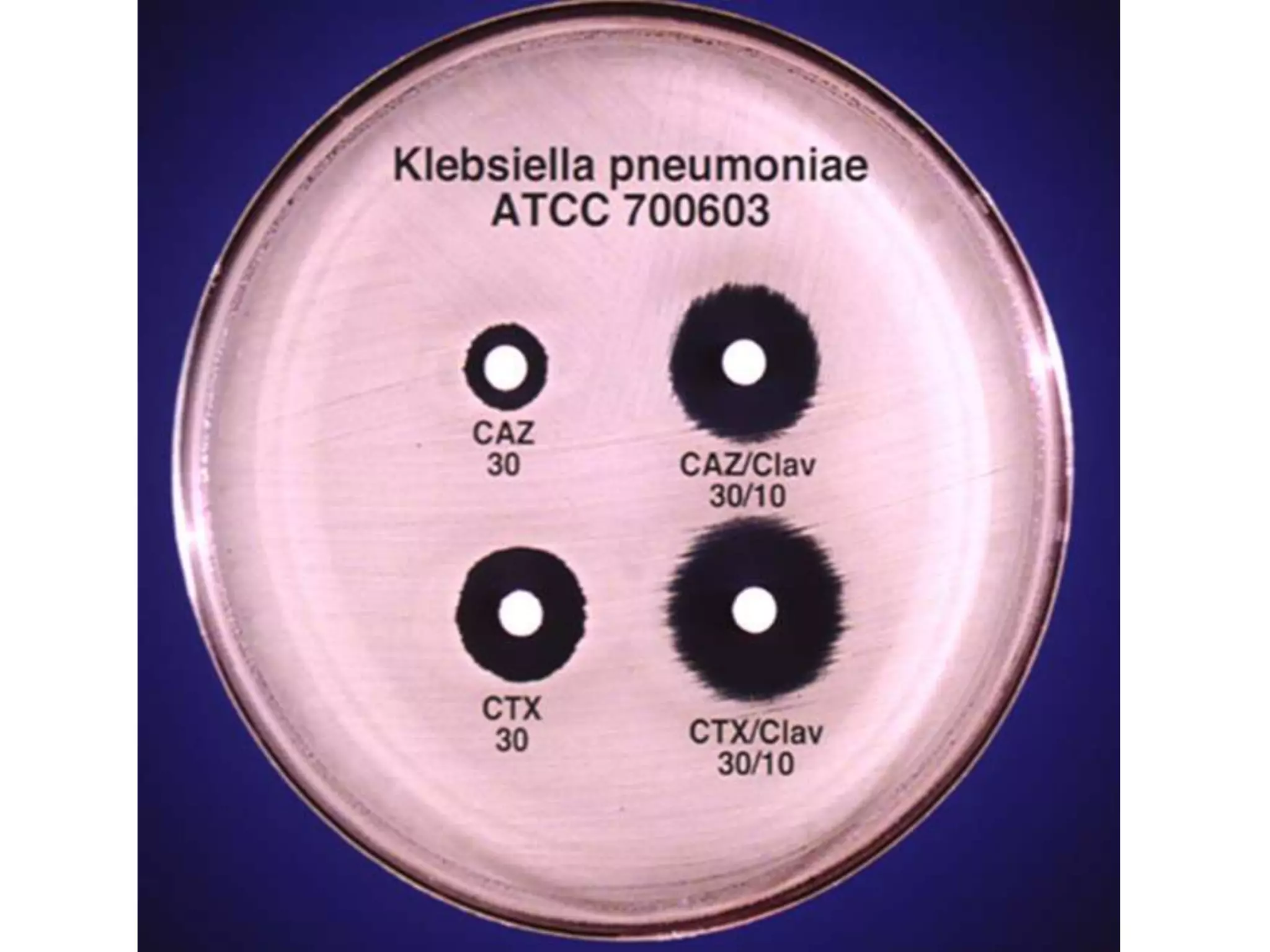

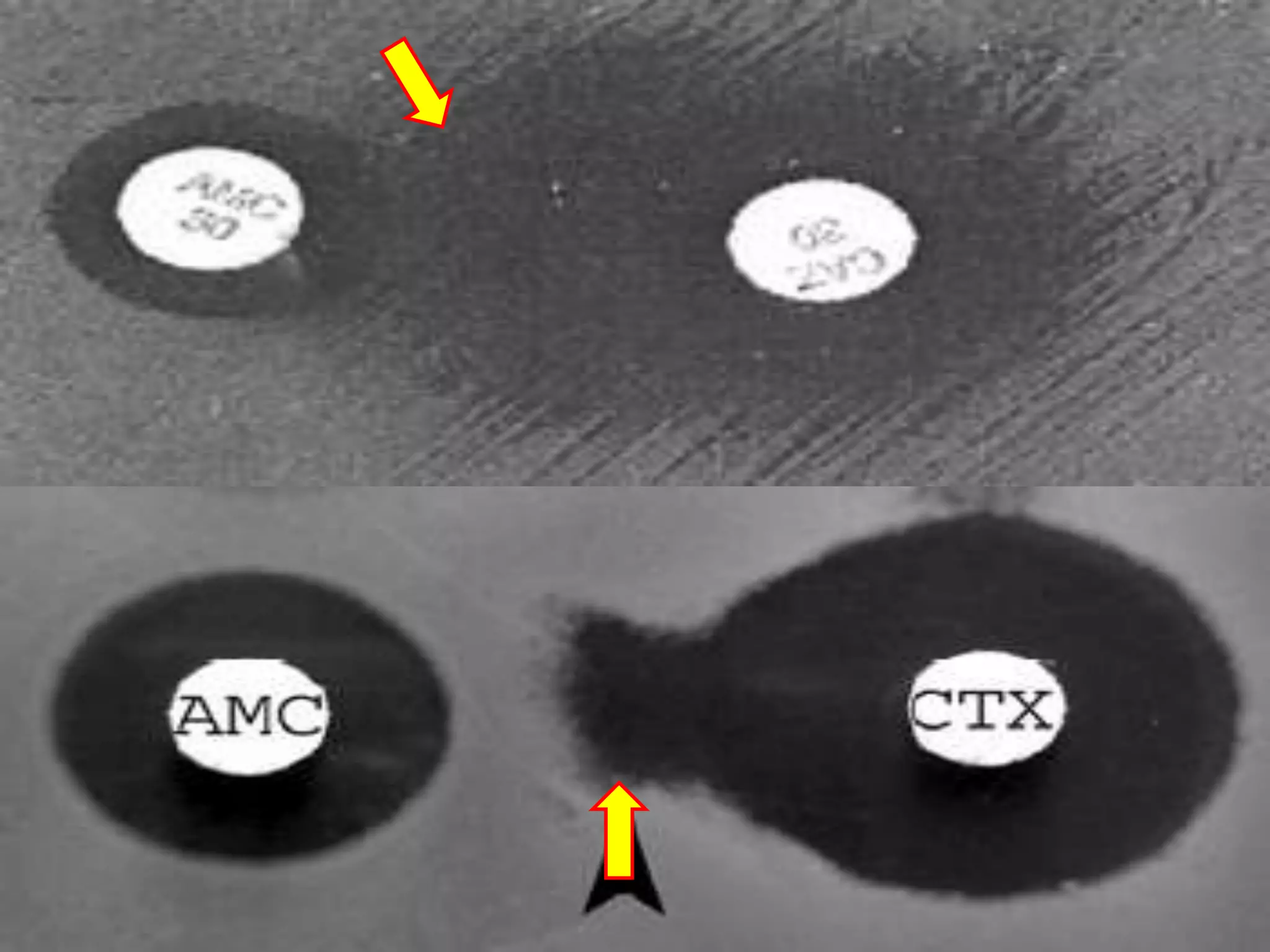

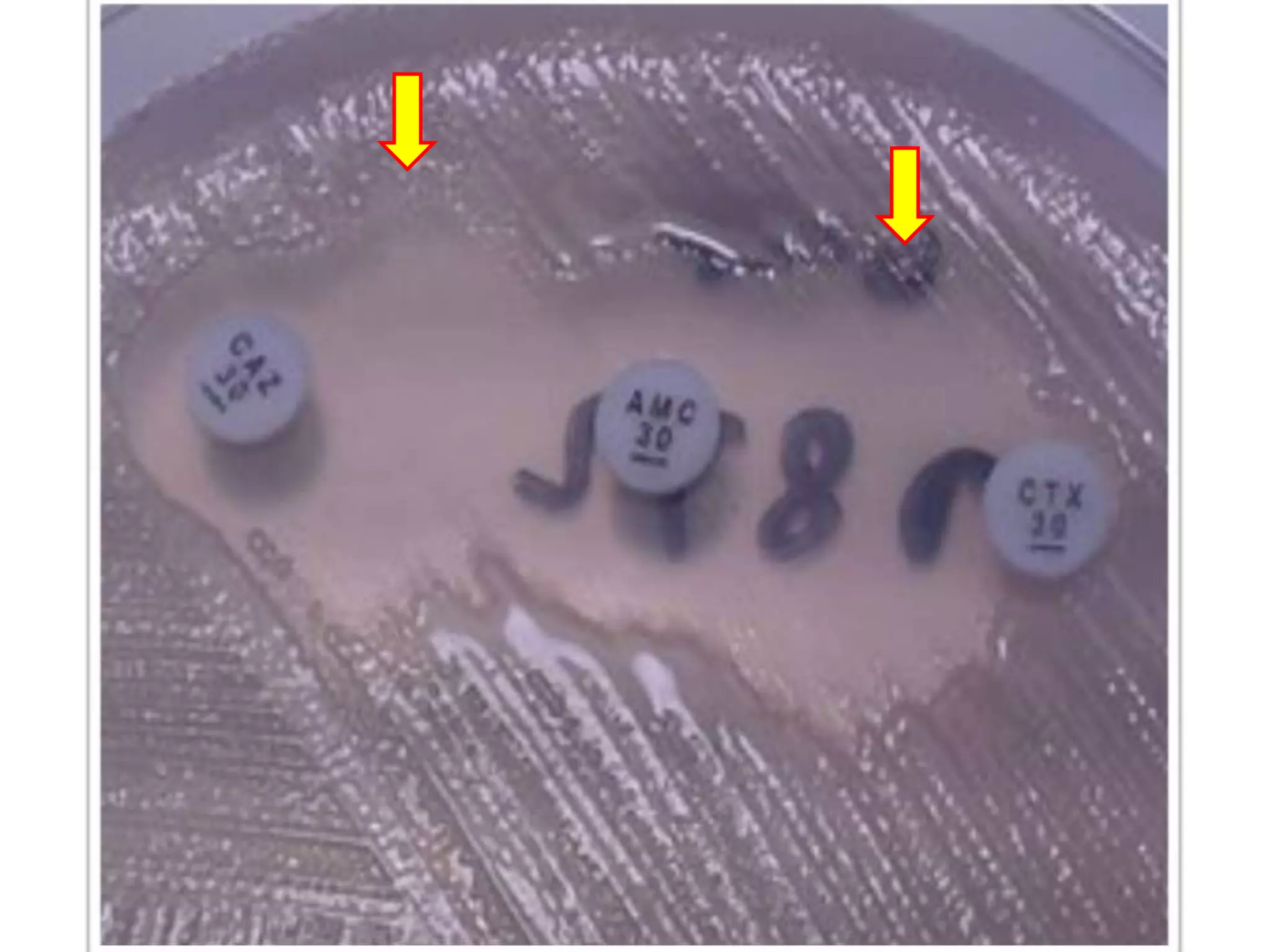

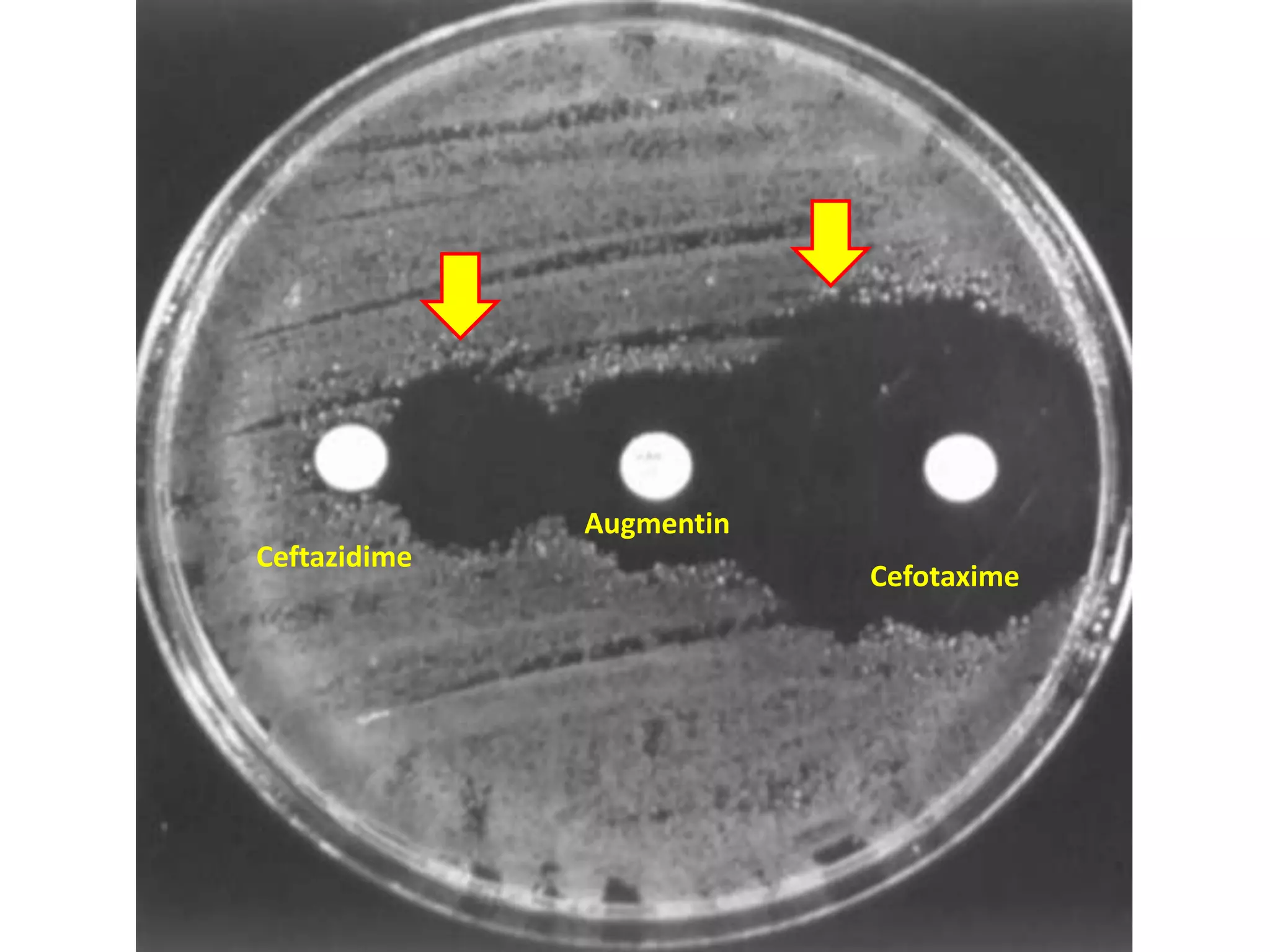

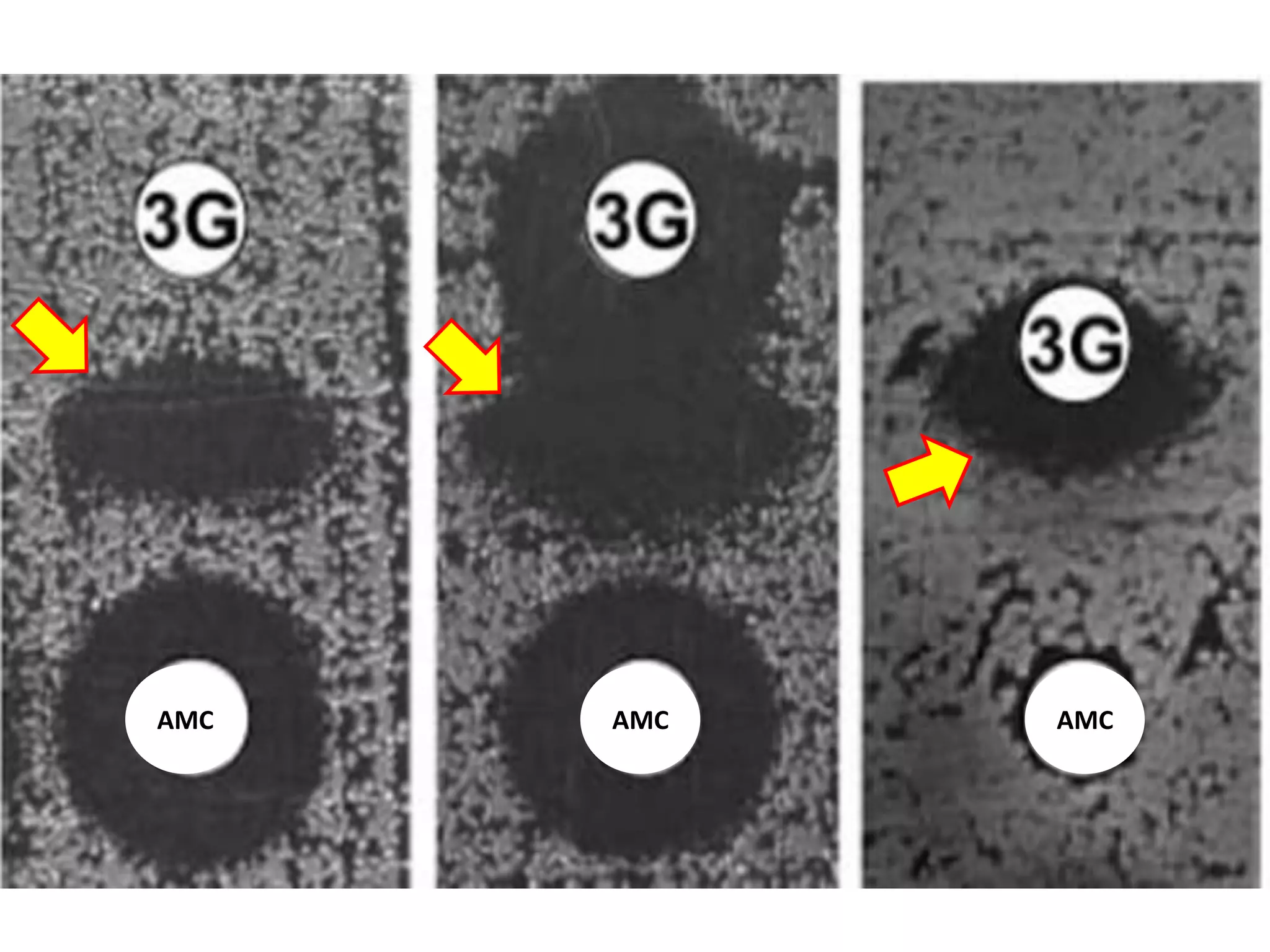

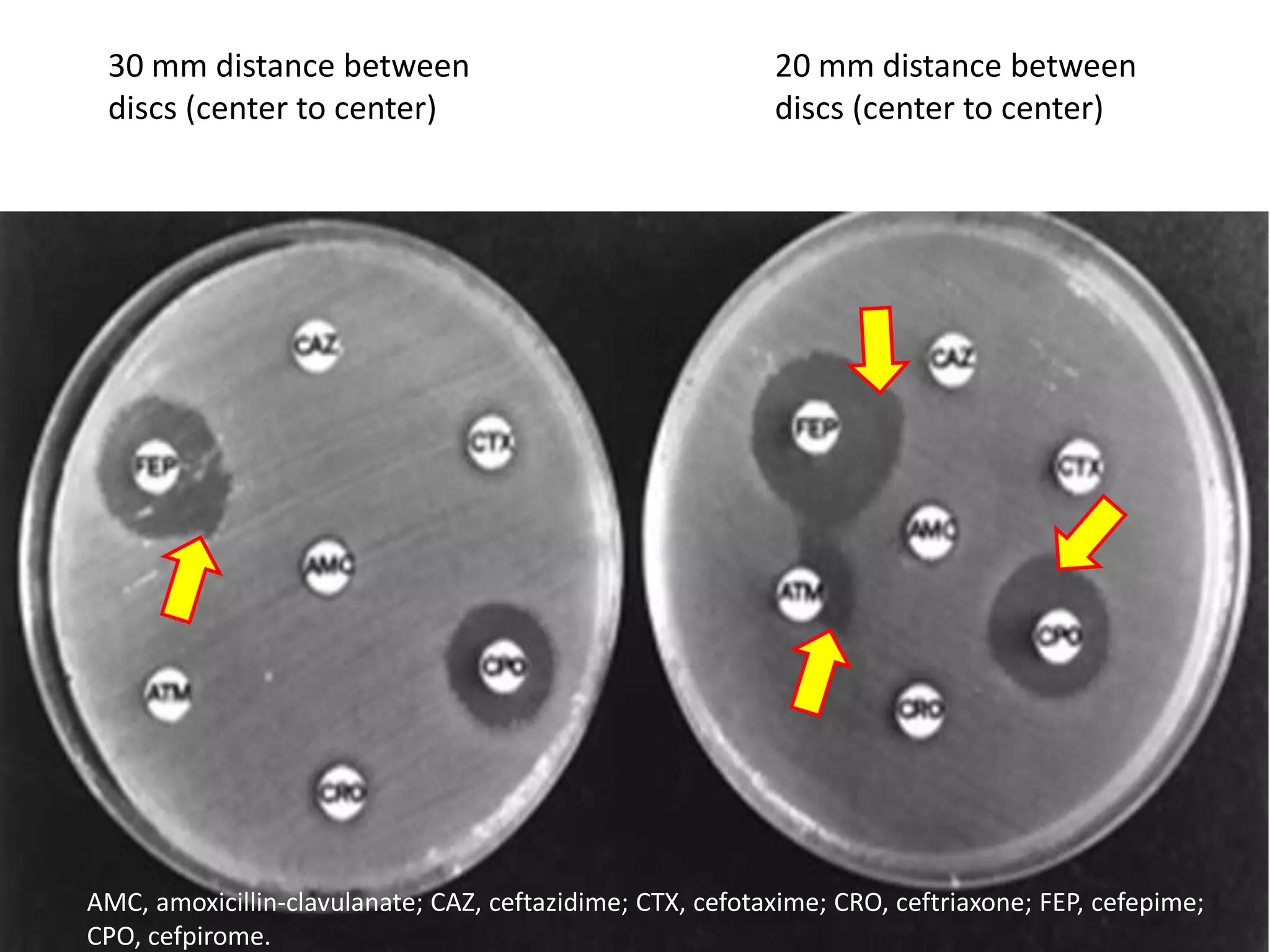

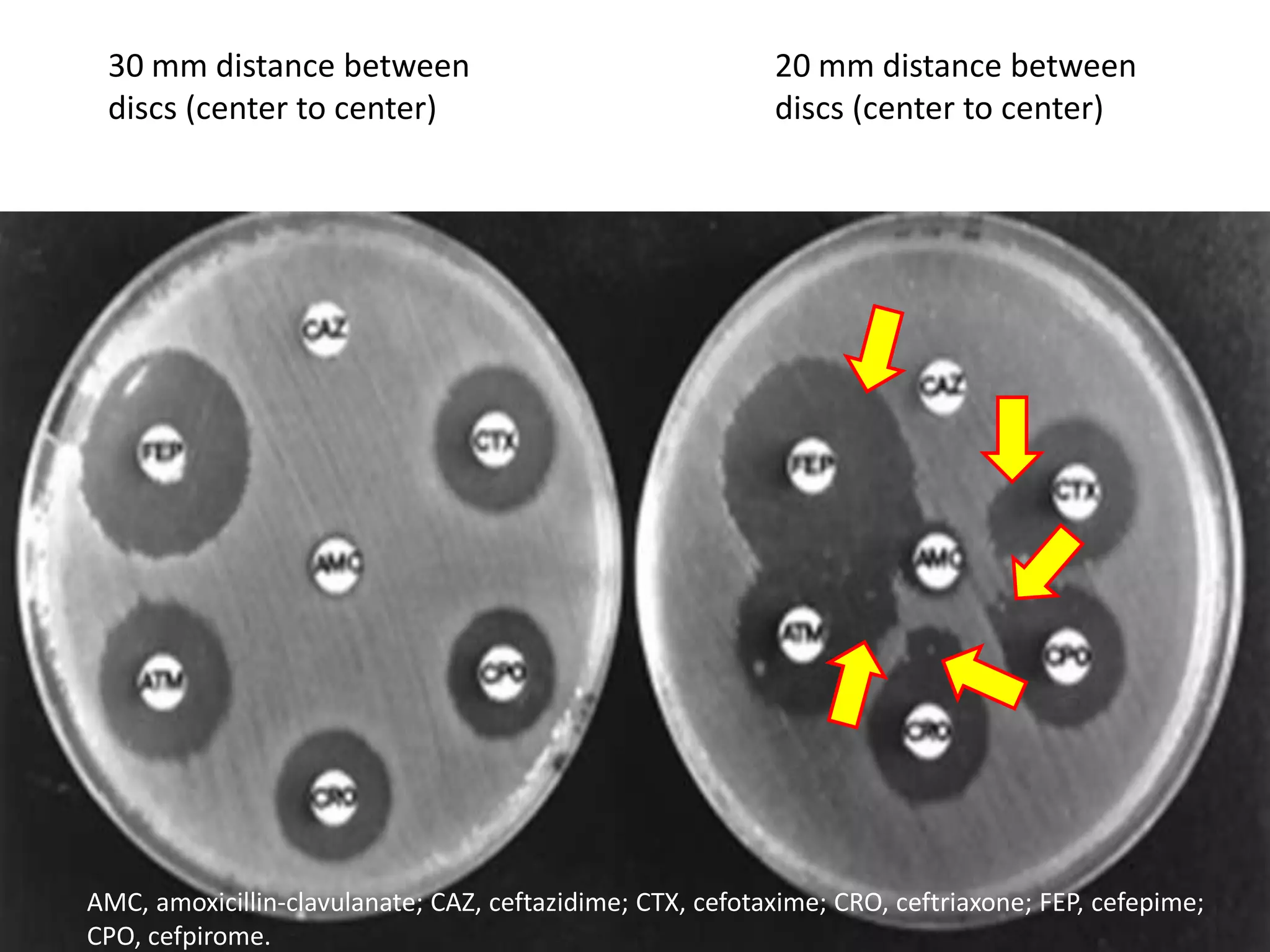

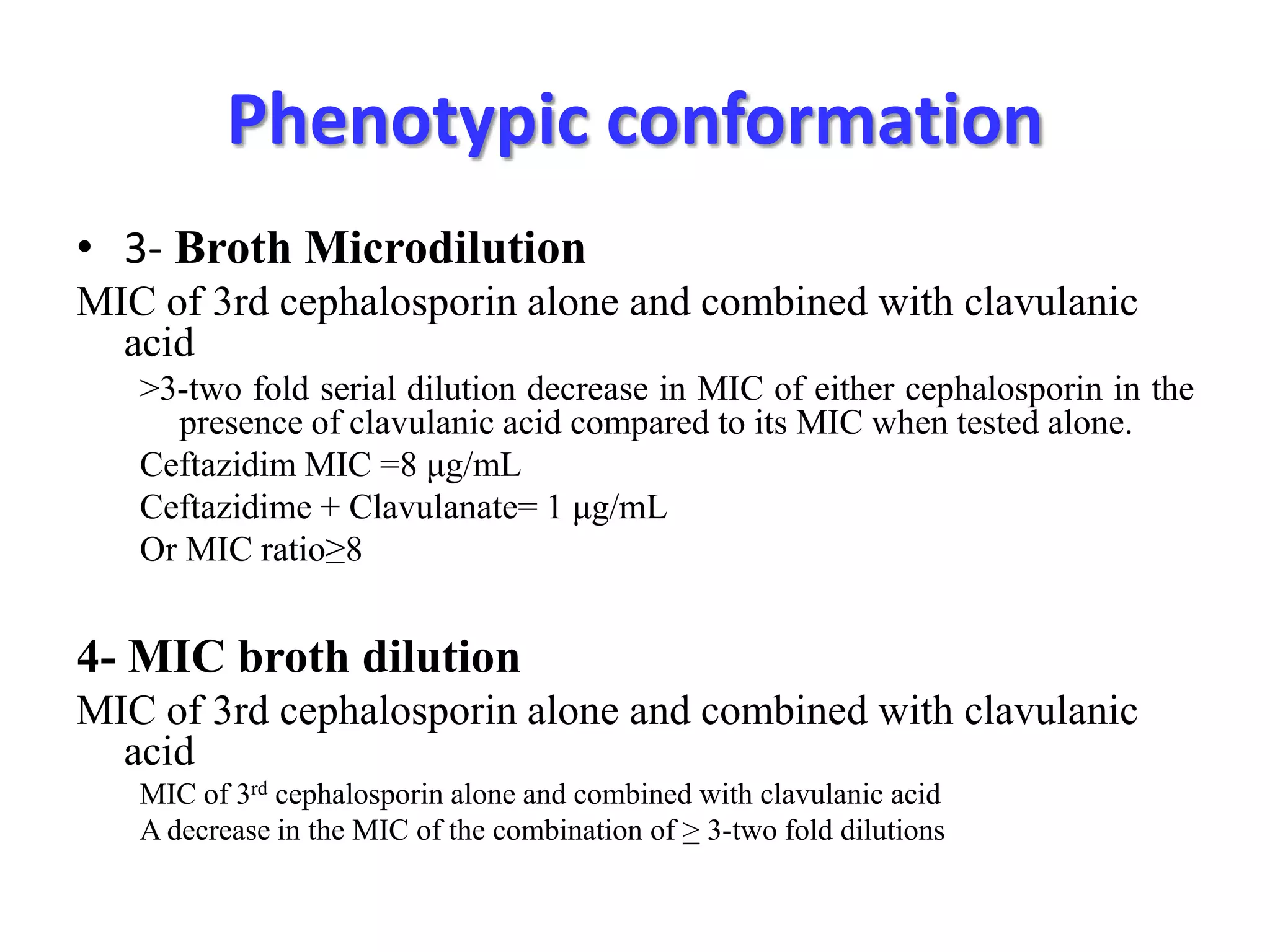

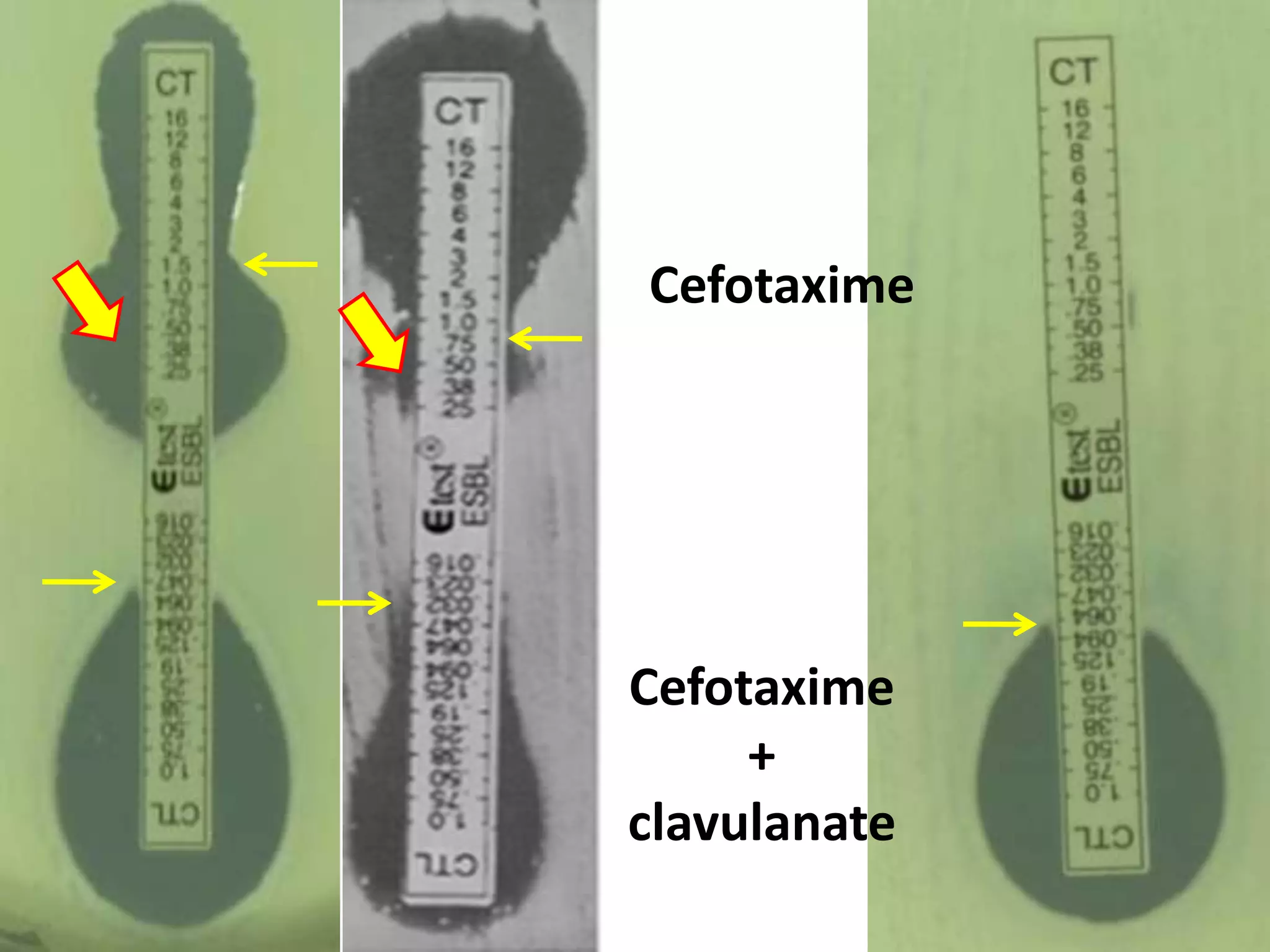

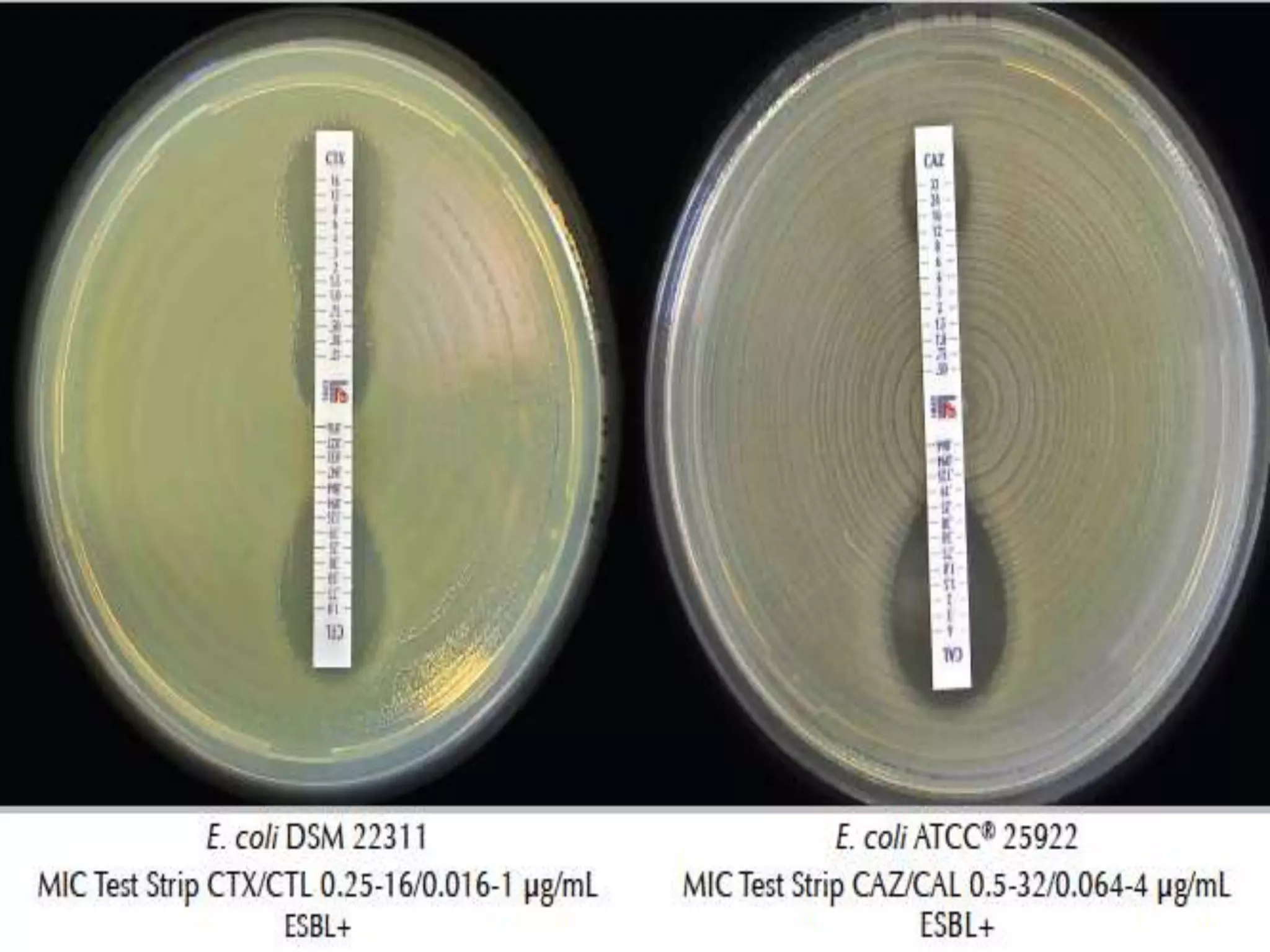

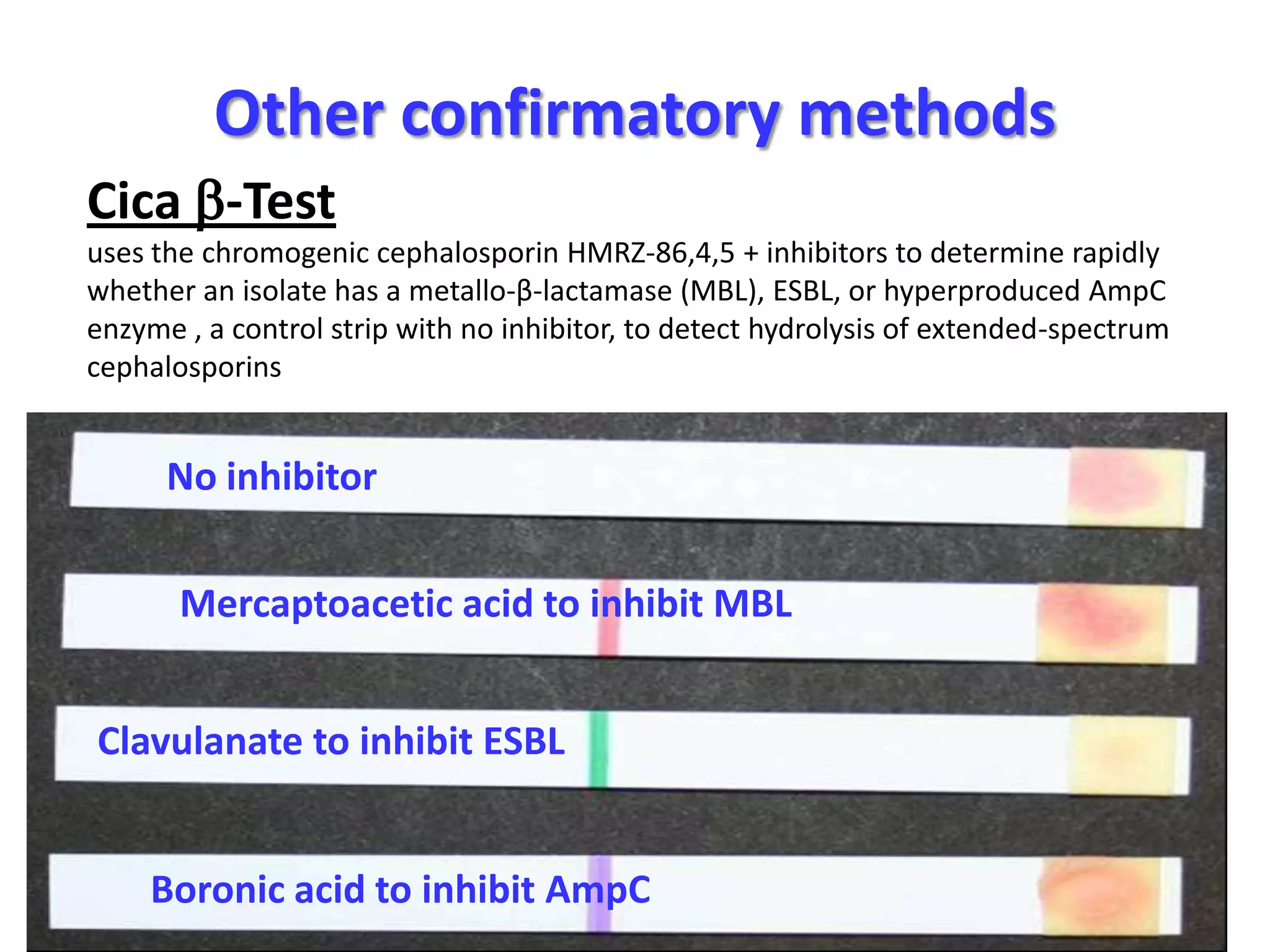

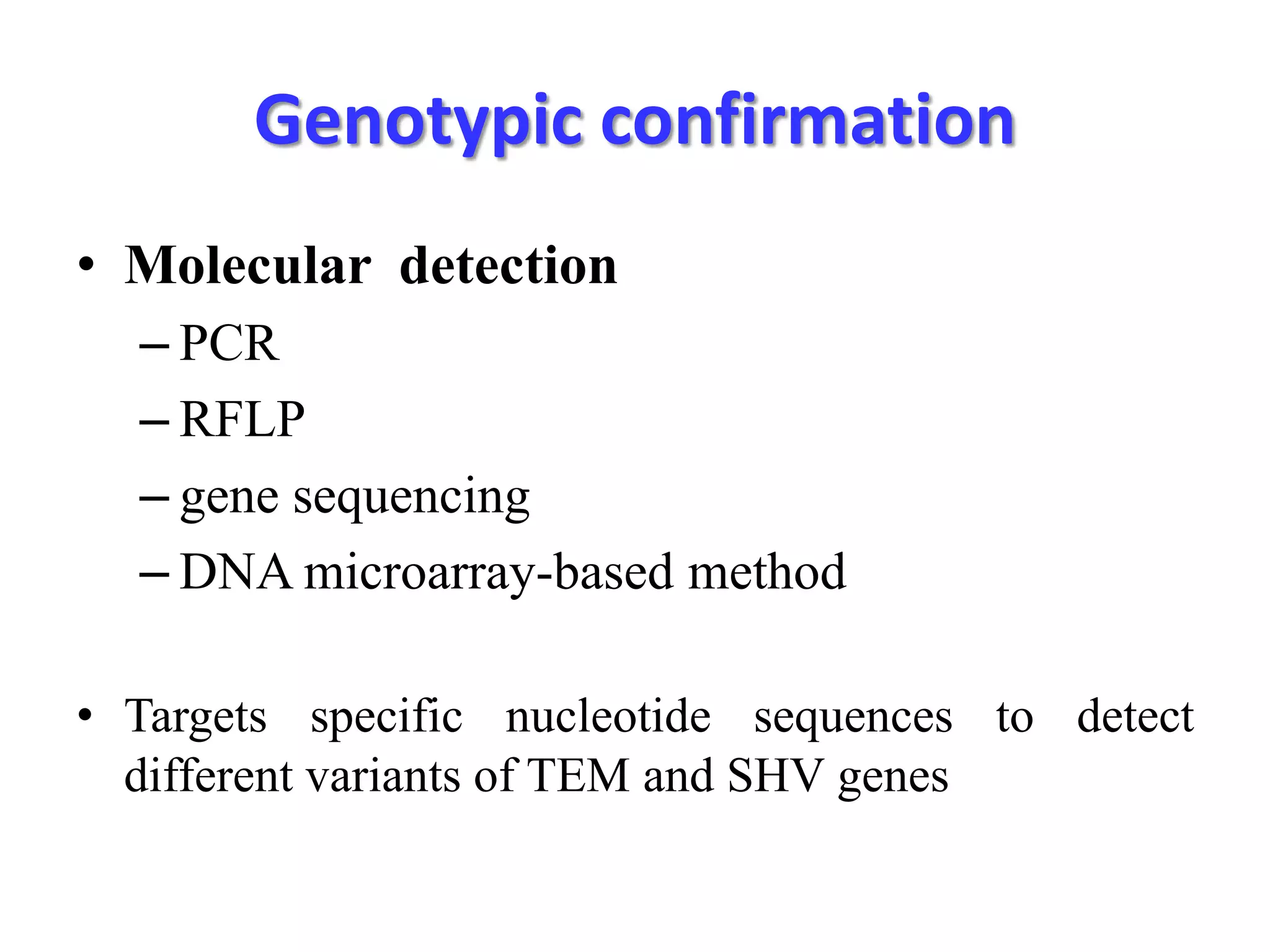

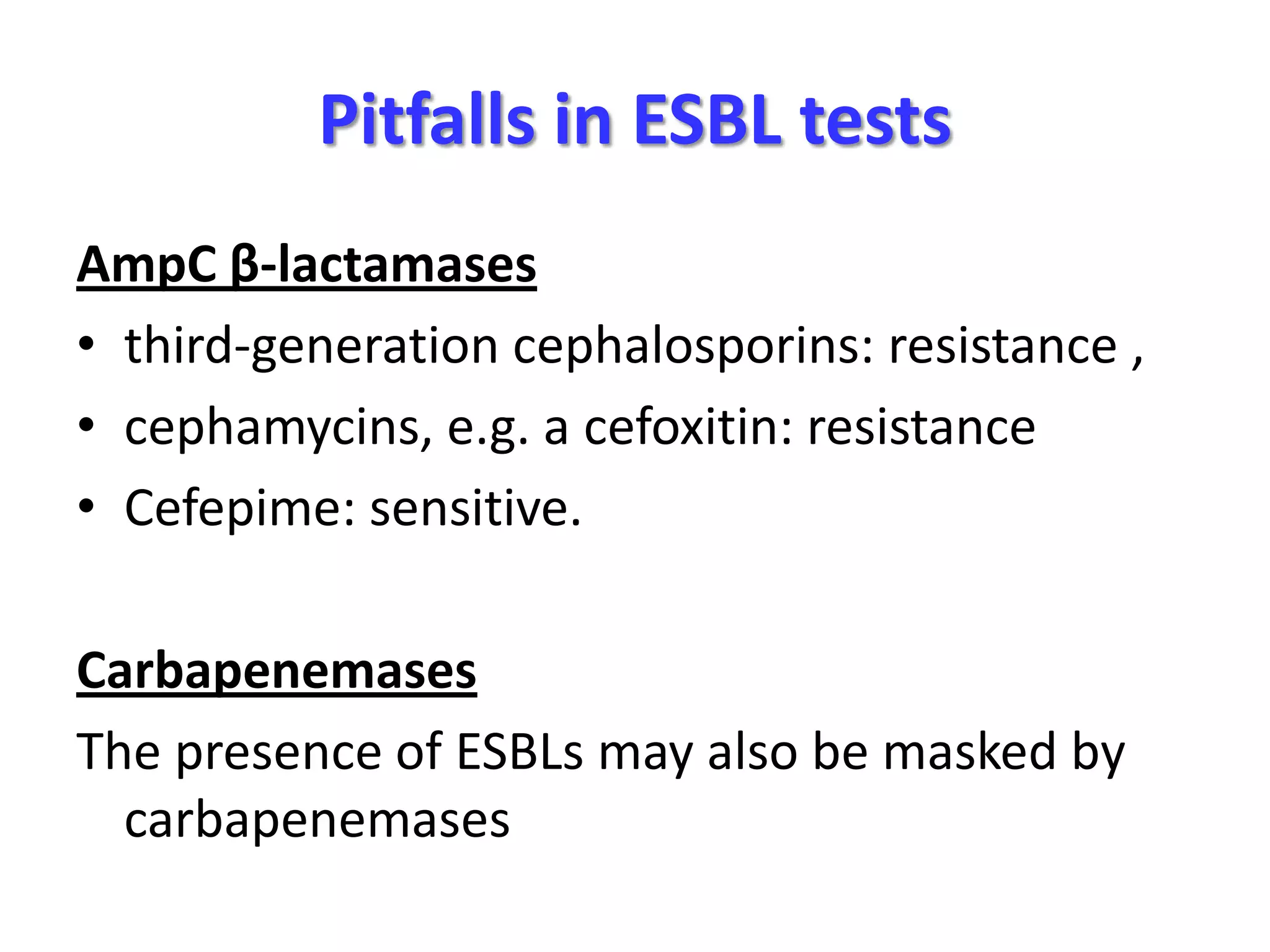

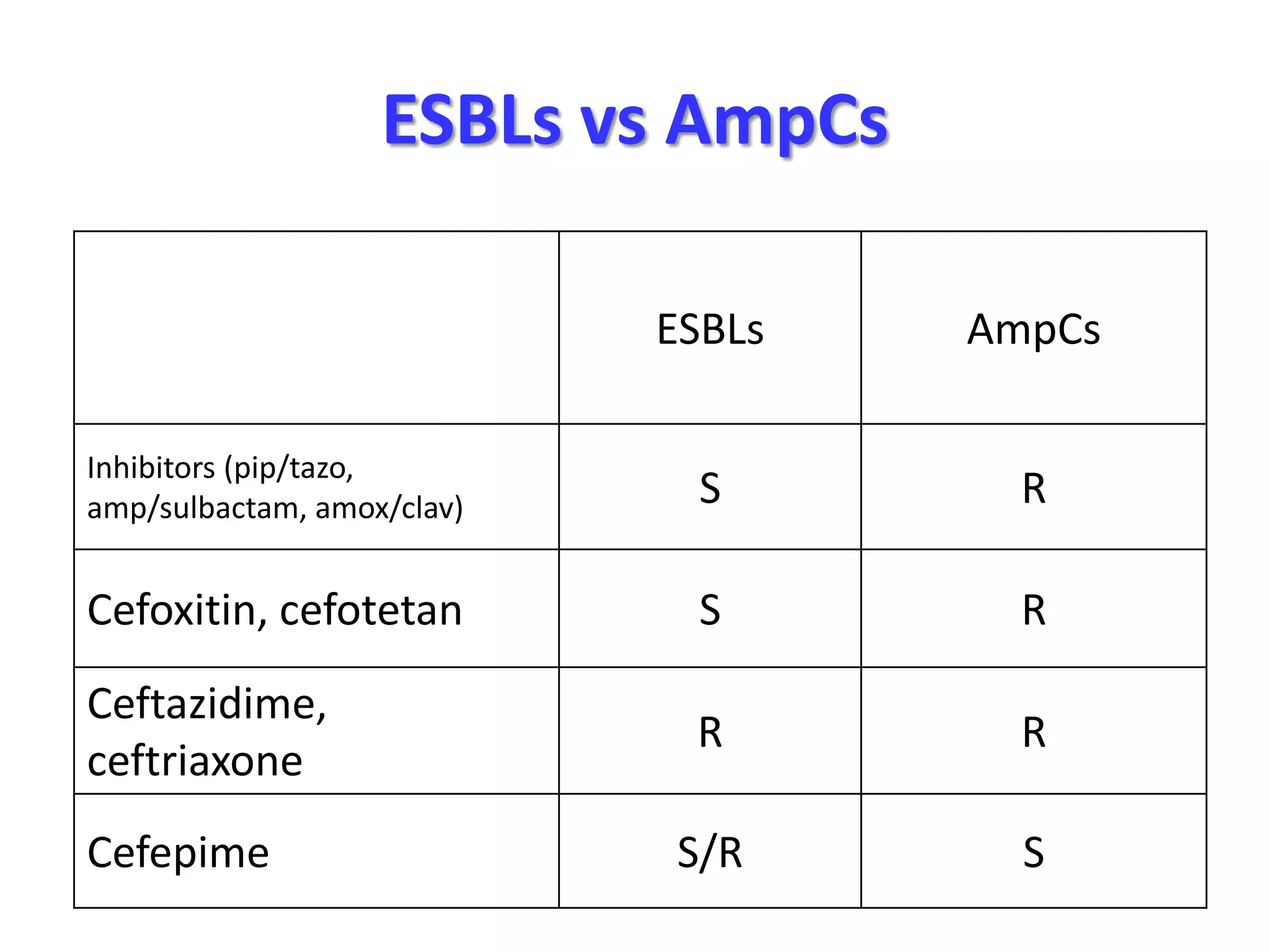

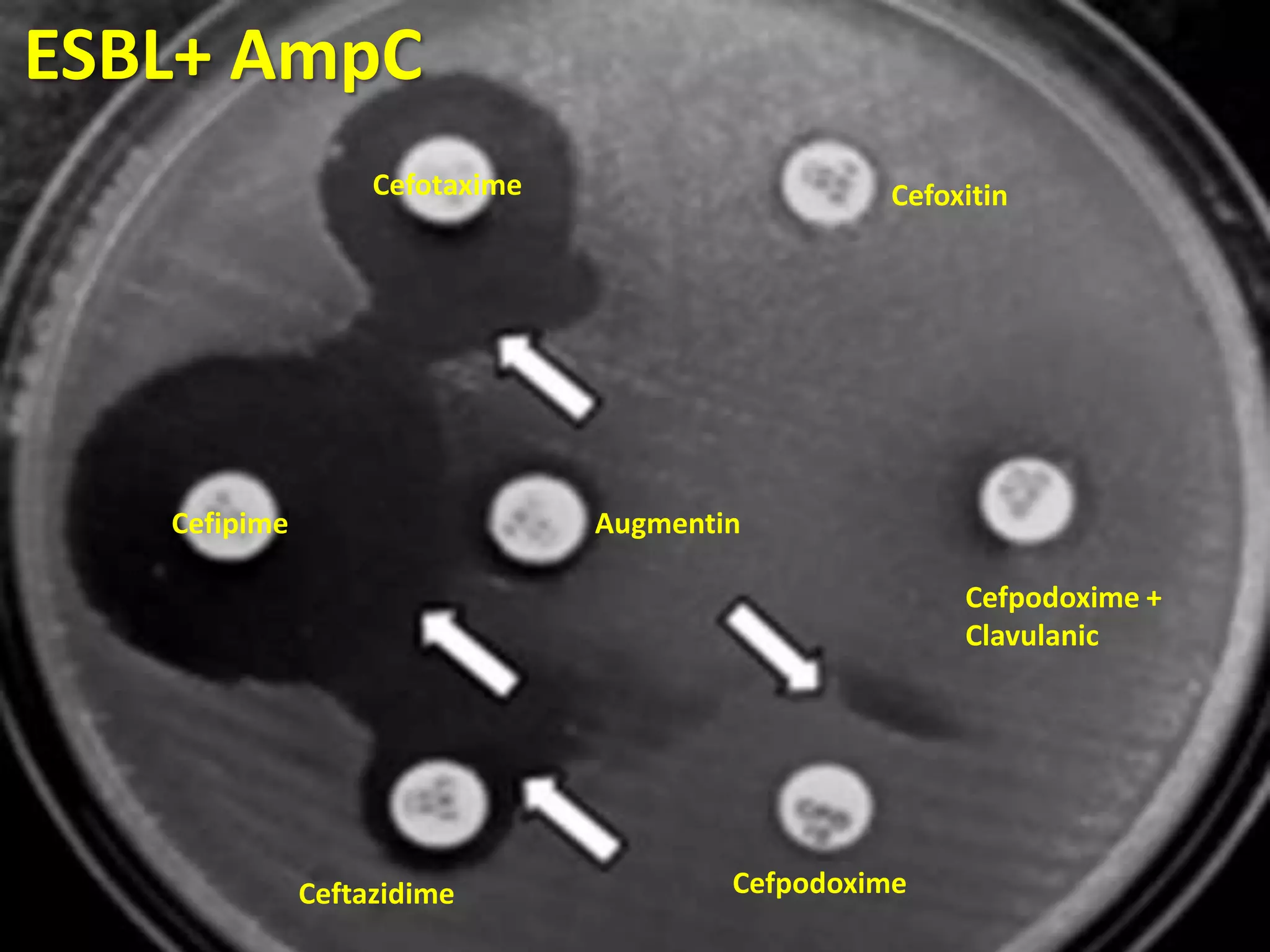

Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) pose challenges for detection and treatment. ESBLs hydrolyze many penicillins and cephalosporins but are inhibited by β-lactamase inhibitors. Delayed or incorrect detection of ESBL producers can lead to inappropriate cephalosporin treatment and worse outcomes. Laboratory detection of ESBLs is complex, requiring screening methods like combination disks or double disk synergy tests followed by confirmatory tests. Genotypic methods can also detect ESBL genes. Accurate detection is important for infection control and antibiotic stewardship given ESBL producers' resistance and transmission risks.