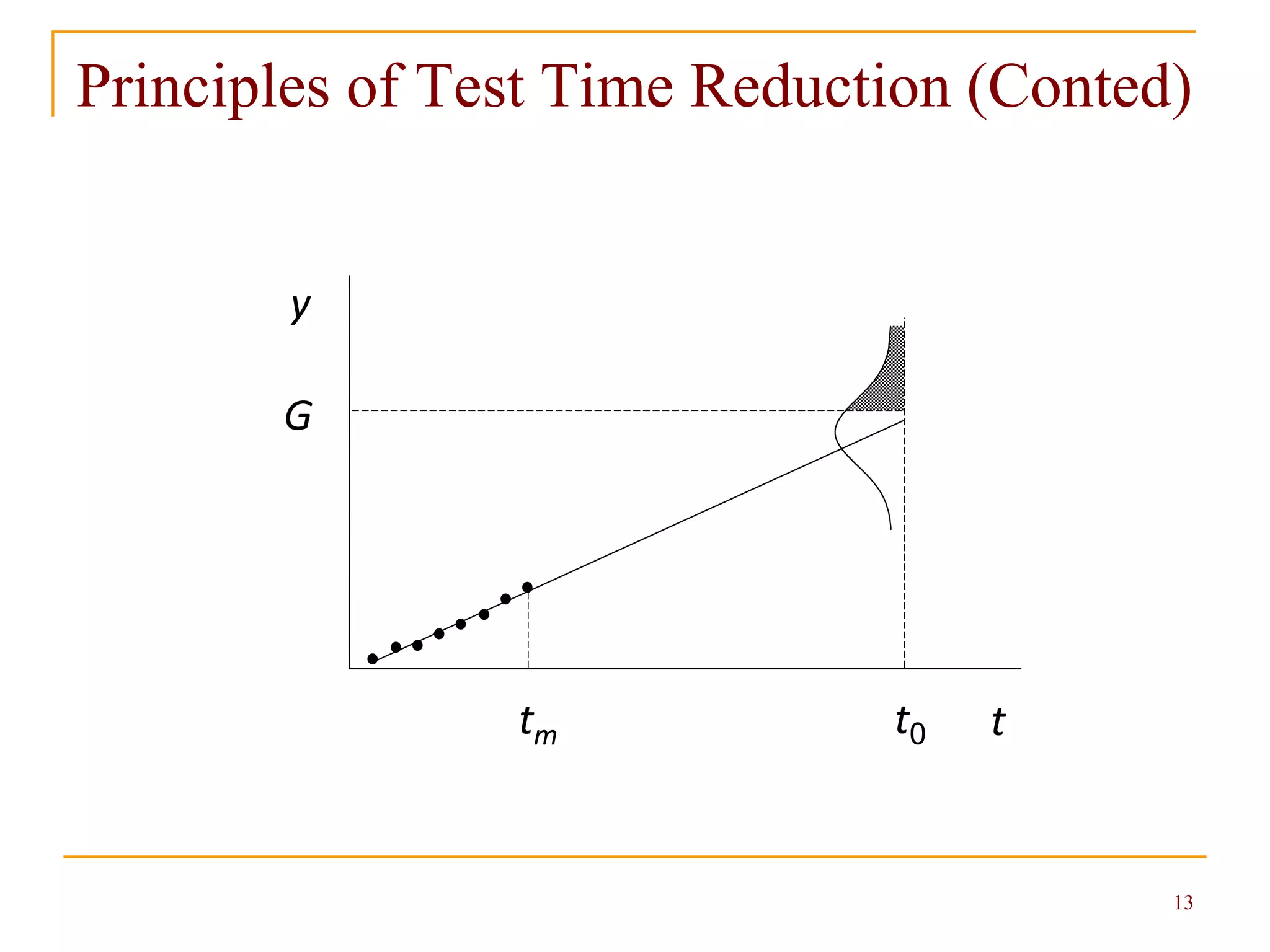

This document discusses efficient reliability demonstration tests that can reduce sample sizes and test times compared to conventional methods. It presents principles for test time reduction using degradation measurements during testing. Methods are provided for calculating optimal test plans that minimize costs while meeting reliability requirements and risk constraints. Decision rules are given for terminating tests early based on degradation measurements and risk estimates. An example application demonstrates how the approach can significantly reduce testing costs.

![8

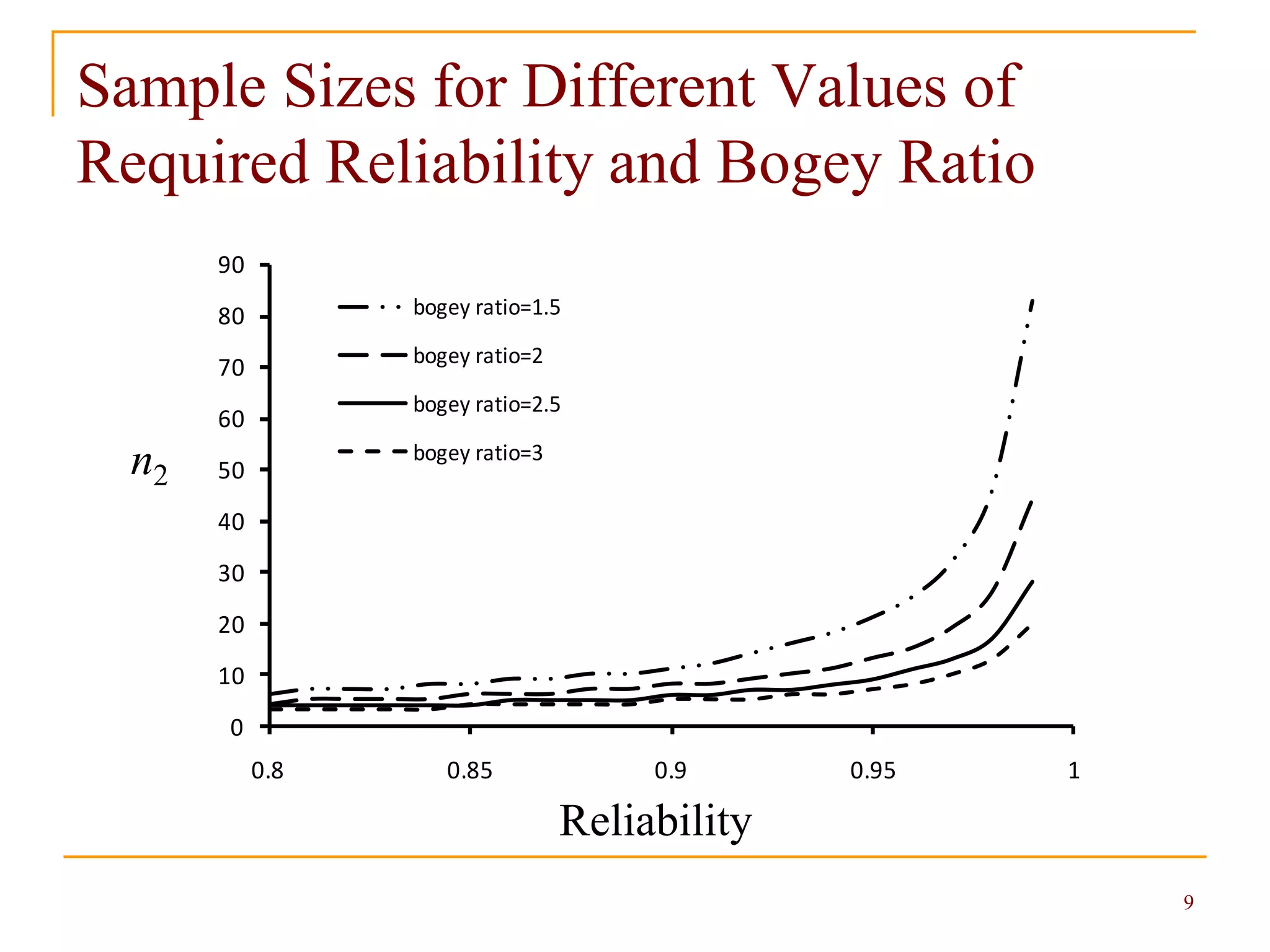

Sample Size for Conventional Lognormal

Bogey Testing

In some situations, the life of products can be

reasonably modeled by lognormal distribution.

The minimum sample size to demonstrate the

reliability requirement is

where is called the bogey ratio, which is the ratio

of actual test time to t0.

The equation indicates that the sample size can be

reduced by increasing the test time.

)]}1(/)ln([ln{

)ln(

0

12

R

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efficientreliabilitydemonstrationtests-140609150614-phpapp02/75/Efficient-Reliability-Demonstration-Tests-by-Guangbin-Yang-8-2048.jpg)

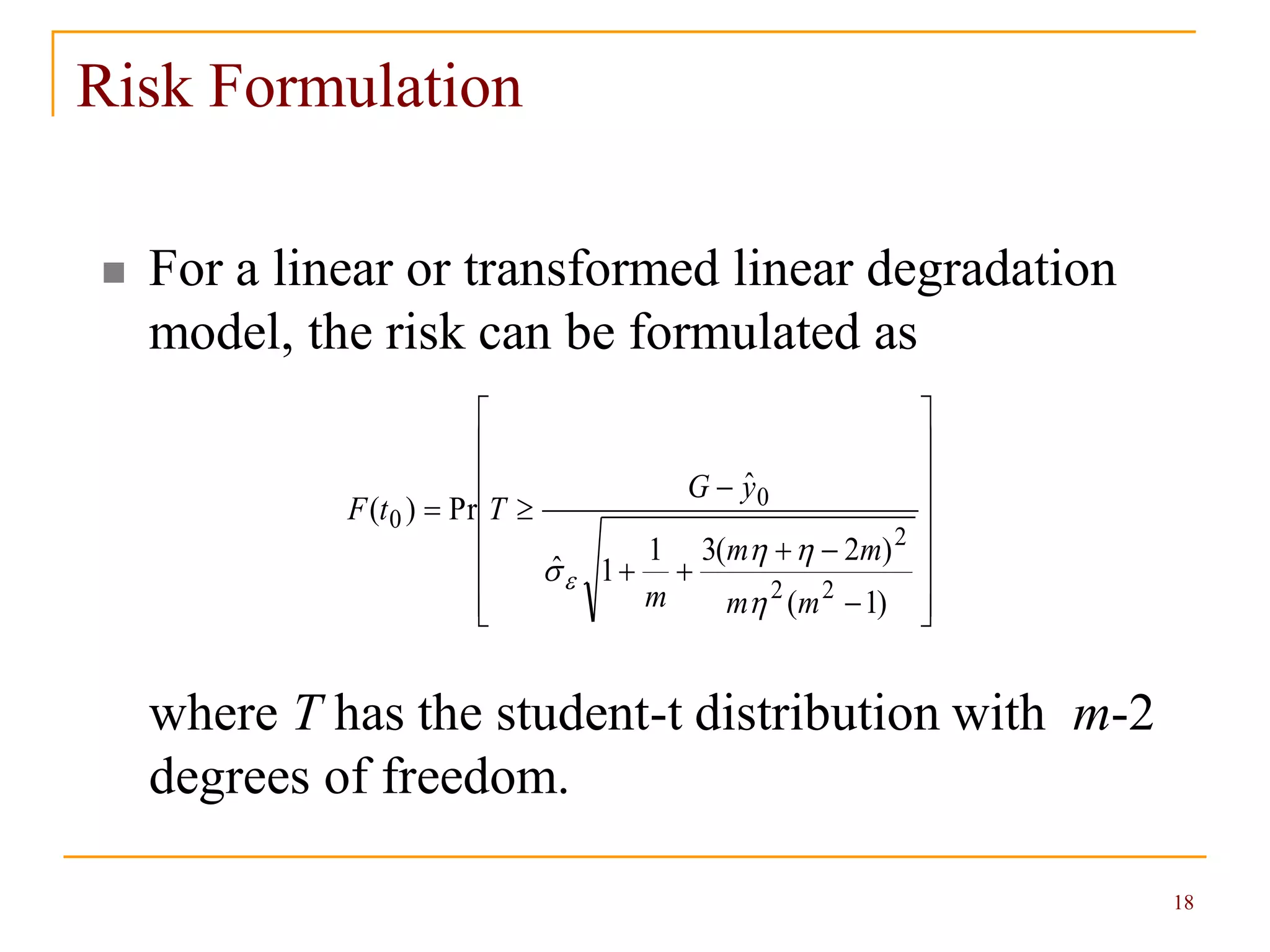

![14

Sample Size for Reduced Test Time

When the test time is reduced, the type II error is

increased by c.

The minimum sample size for the lognormal

distribution is

where = c /.

)]}1(/)ln([ln{

)1ln()ln(

0

13

R

n

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efficientreliabilitydemonstrationtests-140609150614-phpapp02/75/Efficient-Reliability-Demonstration-Tests-by-Guangbin-Yang-14-2048.jpg)

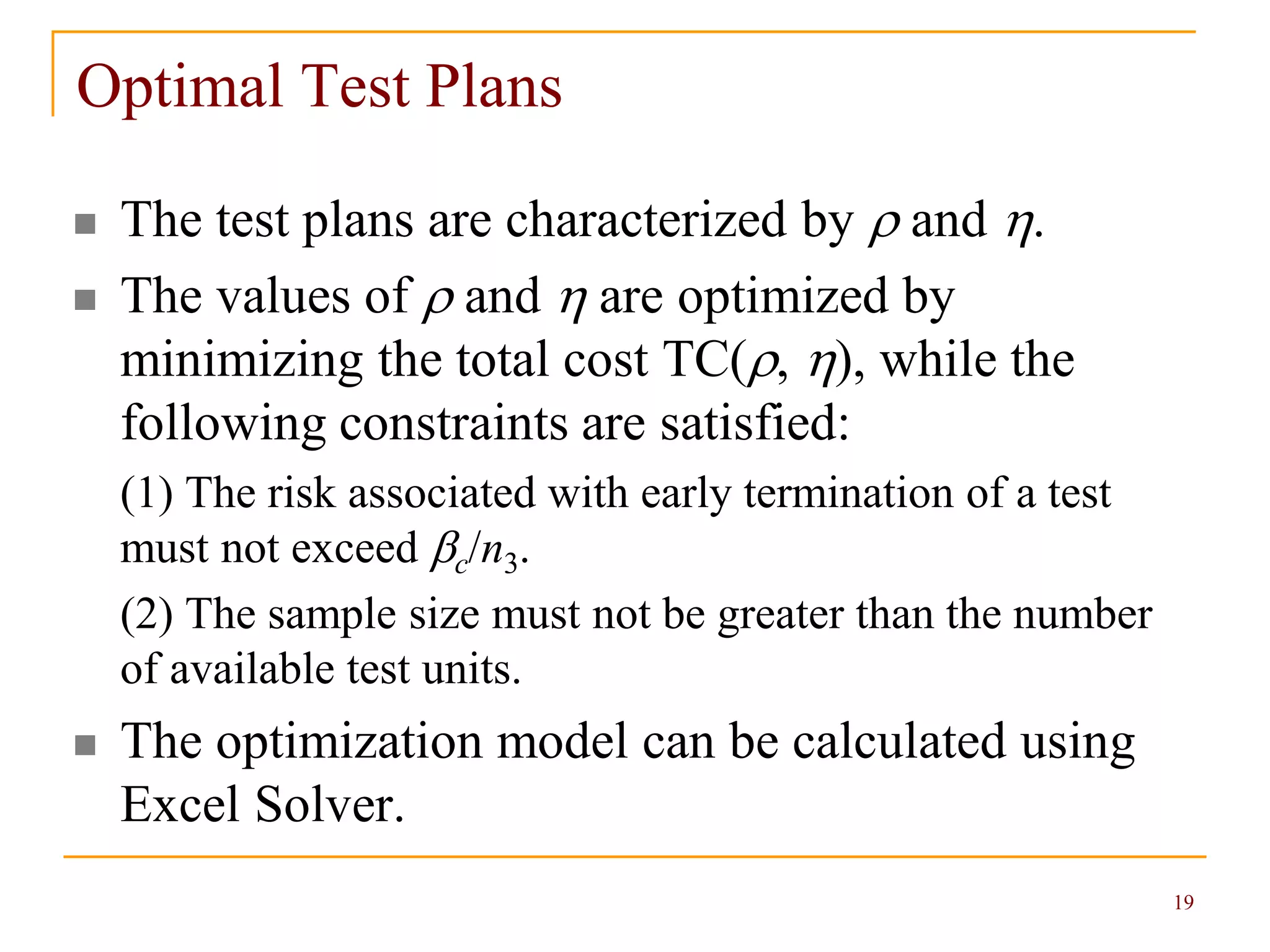

![15

Test Cost Modeling

The cost of a bogey test consists of

the cost of conducting the test,

the cost of samples, and

the cost of measurements.

Cost model

)(

)]}1(/)ln([ln{

)1ln()ln(

),( 32

0

101 mcc

R

tcTC

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/efficientreliabilitydemonstrationtests-140609150614-phpapp02/75/Efficient-Reliability-Demonstration-Tests-by-Guangbin-Yang-15-2048.jpg)