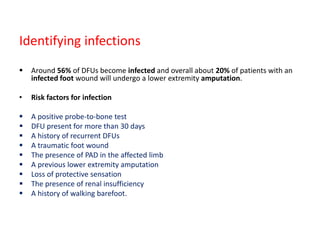

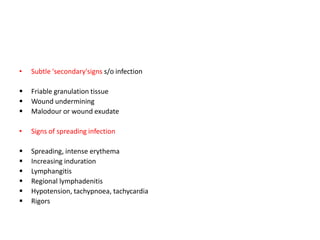

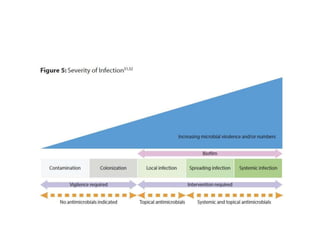

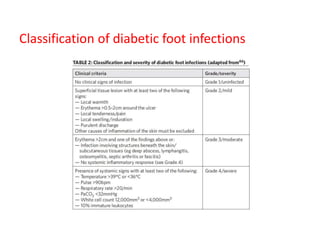

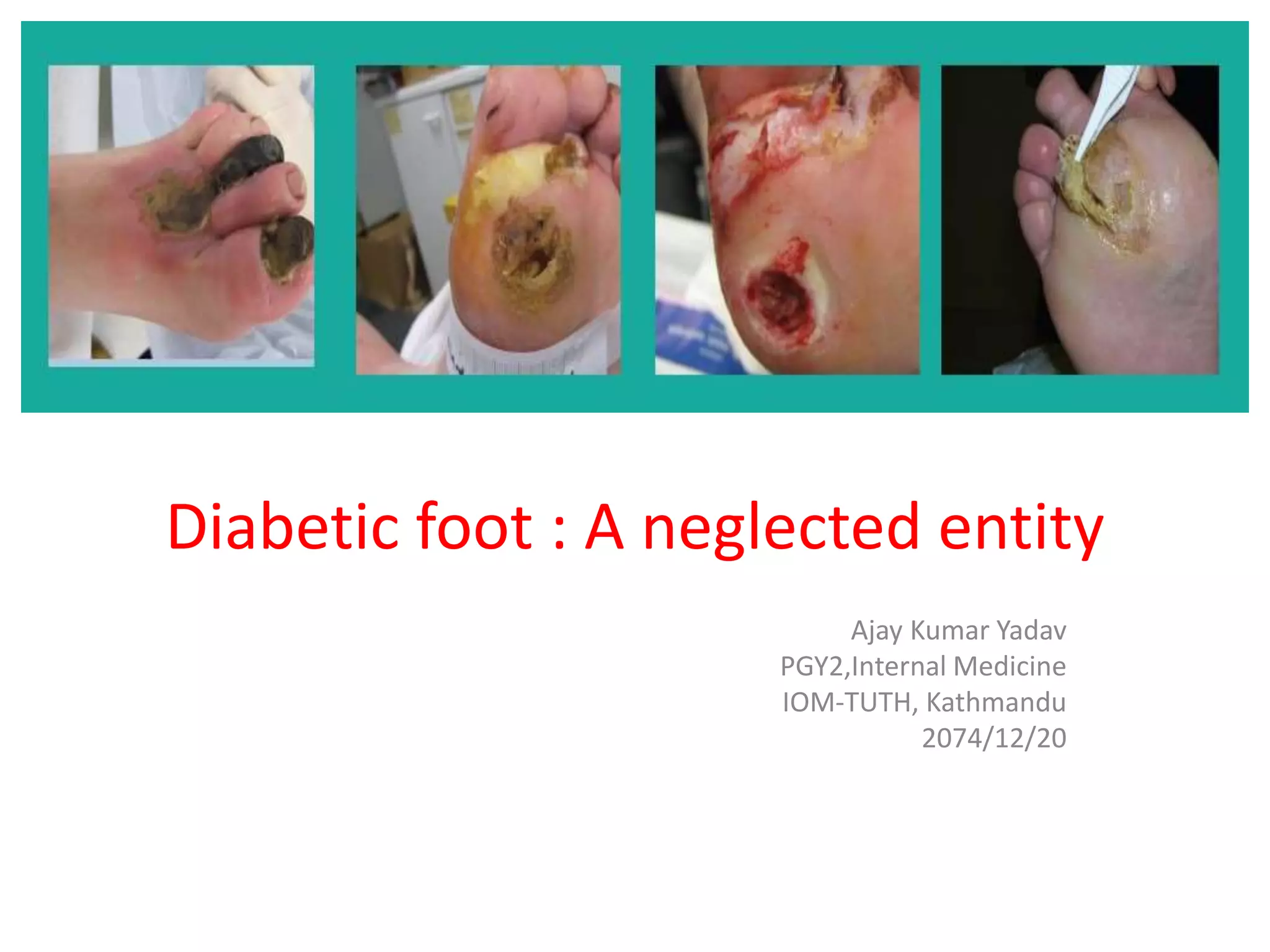

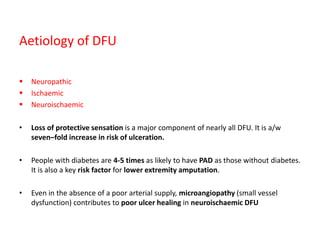

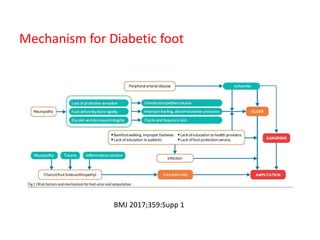

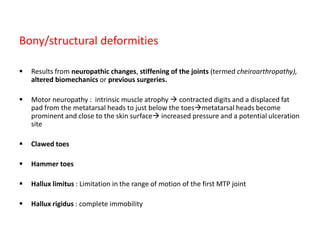

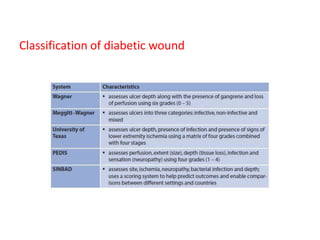

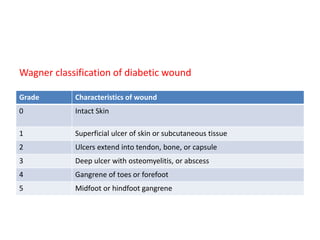

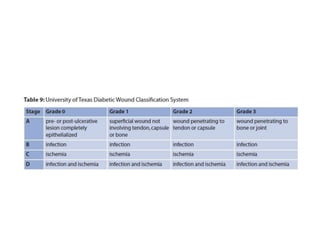

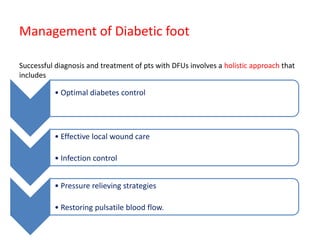

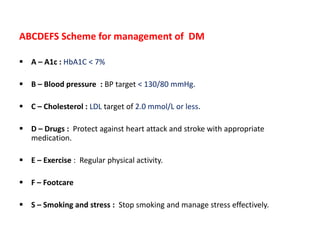

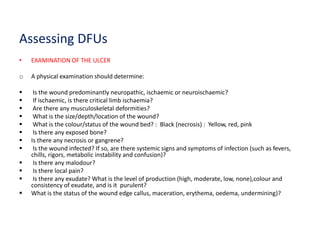

This document discusses diabetic foot, which is an important but often neglected entity. Around 25% of people with diabetes will develop a diabetic foot ulcer in their lifetime, which can lead to amputation and increased mortality. Proper management of diabetic foot involves optimal diabetes and blood pressure control, foot care including regular inspection and debridement of wounds, offloading of pressure areas, and treatment of infections. Assessing the foot involves testing for loss of sensation and vascular status, classifying any wounds, and looking for signs of infection.

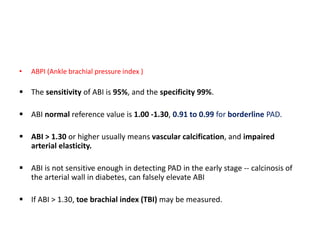

![• Ischemia is defined as an ABI < 0.9 and TBI < 0.75.

ABI 0.71 to 0.90 : mild PAD,

ABI 0.41 to 0.70 : moderate and

≤ 0.40 : severe PAD or critical limb ischaemia

A pt with acute limb ischaemia characterised by the six ‘Ps’ (pulselessness,

pain, pallor [mottled colouration], perishing cold, paraesthesia and paralysis)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diabeticfoot-190101162953/85/Diabetic-foot-27-320.jpg)