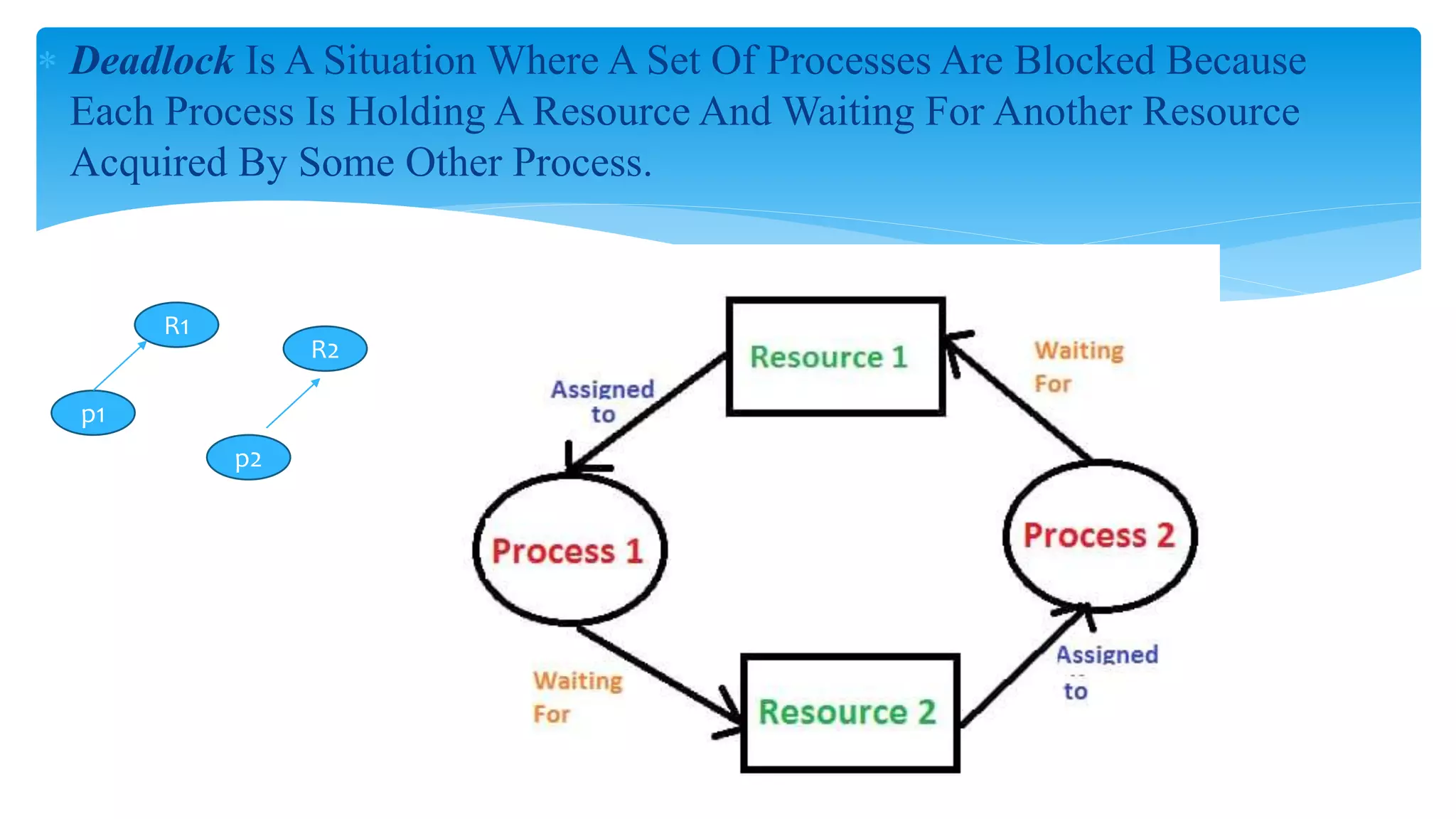

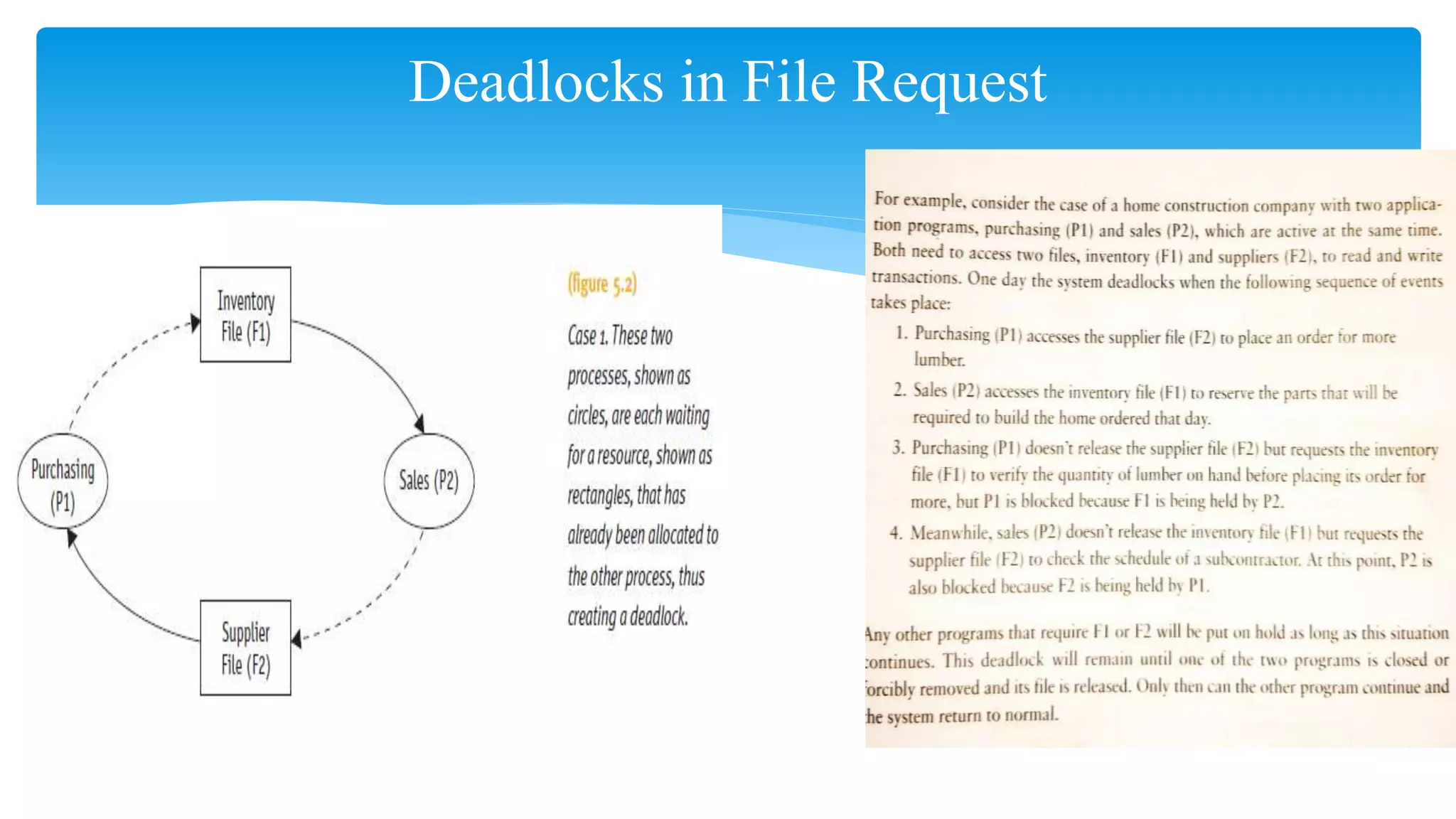

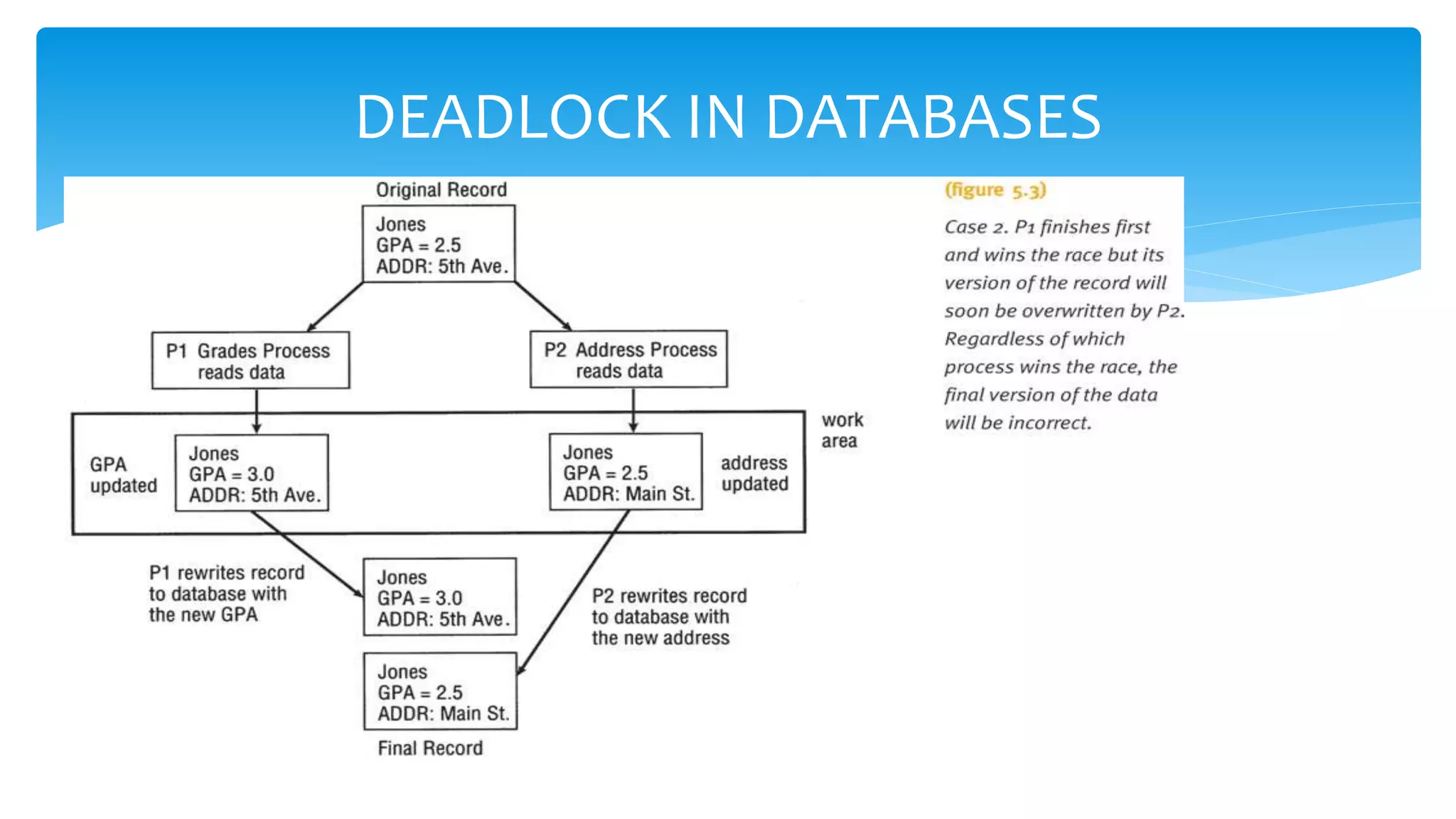

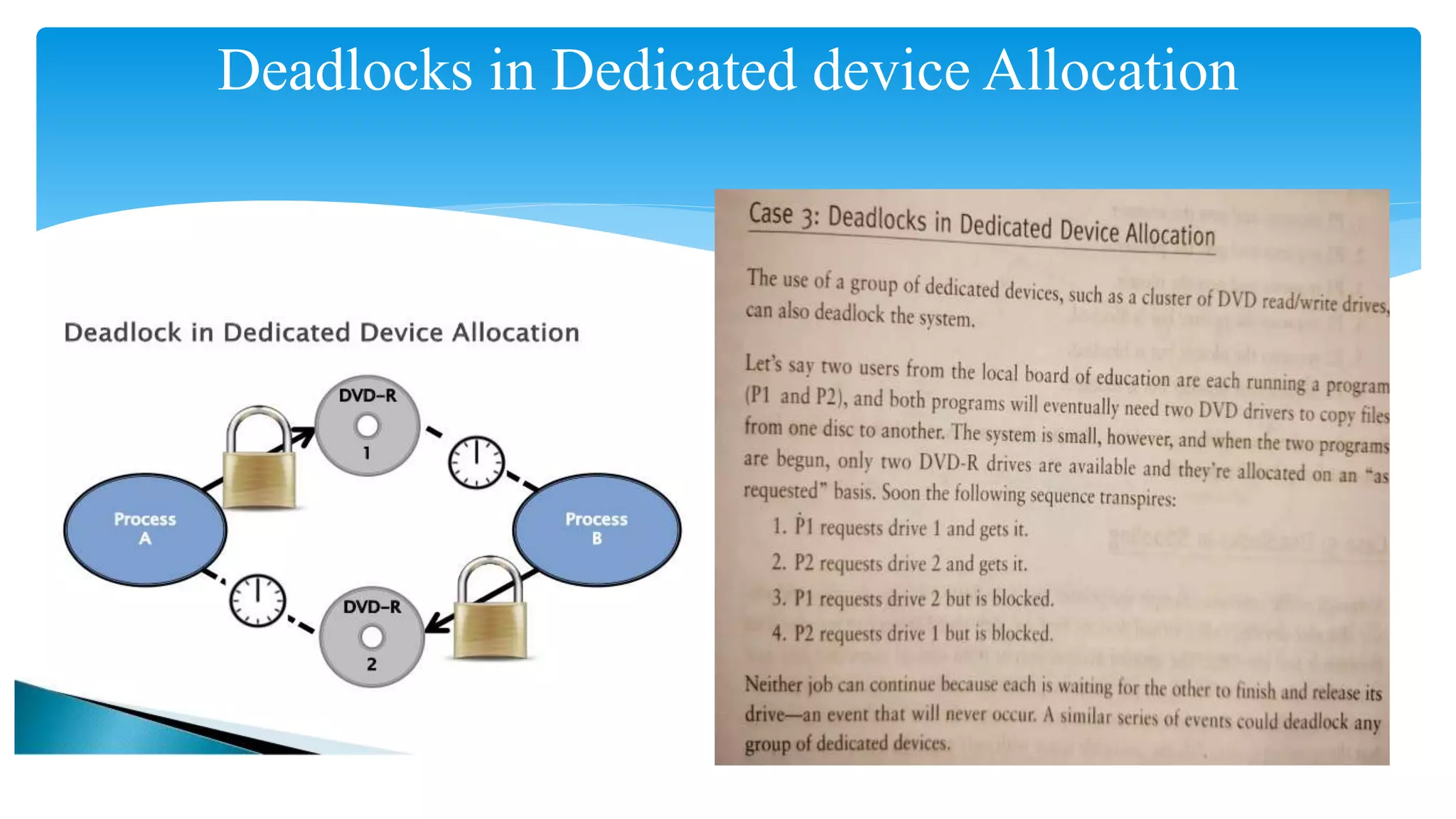

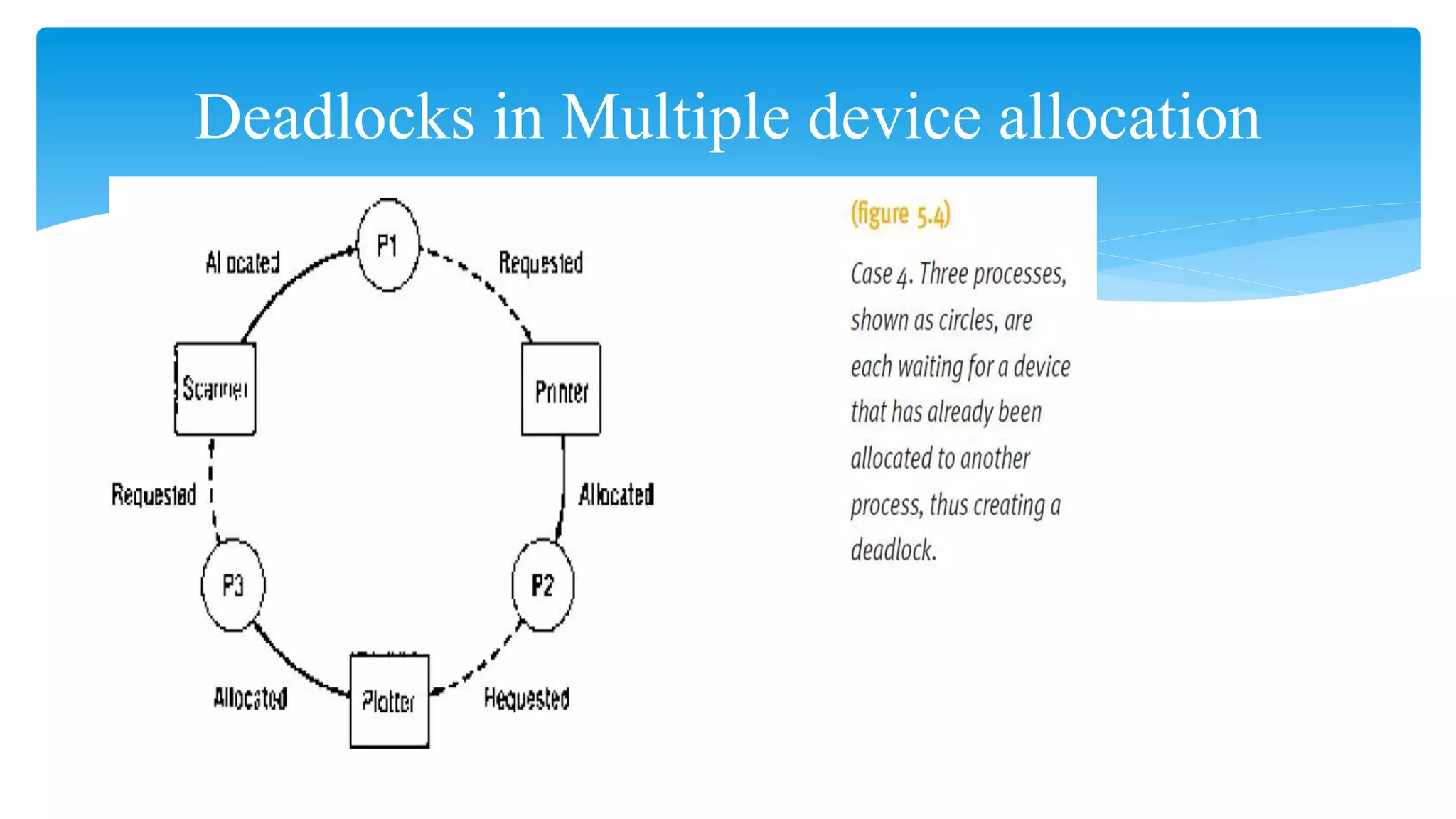

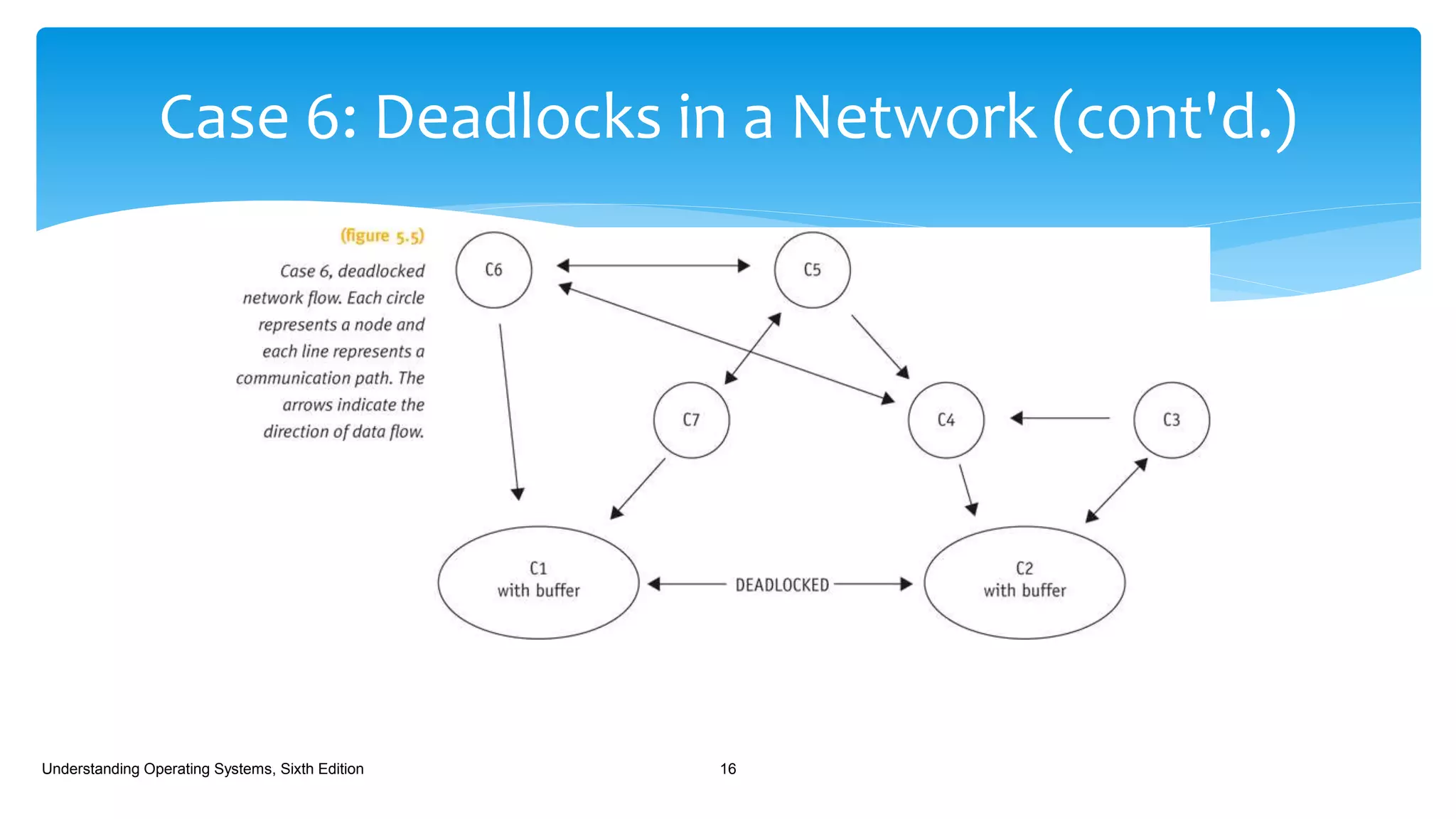

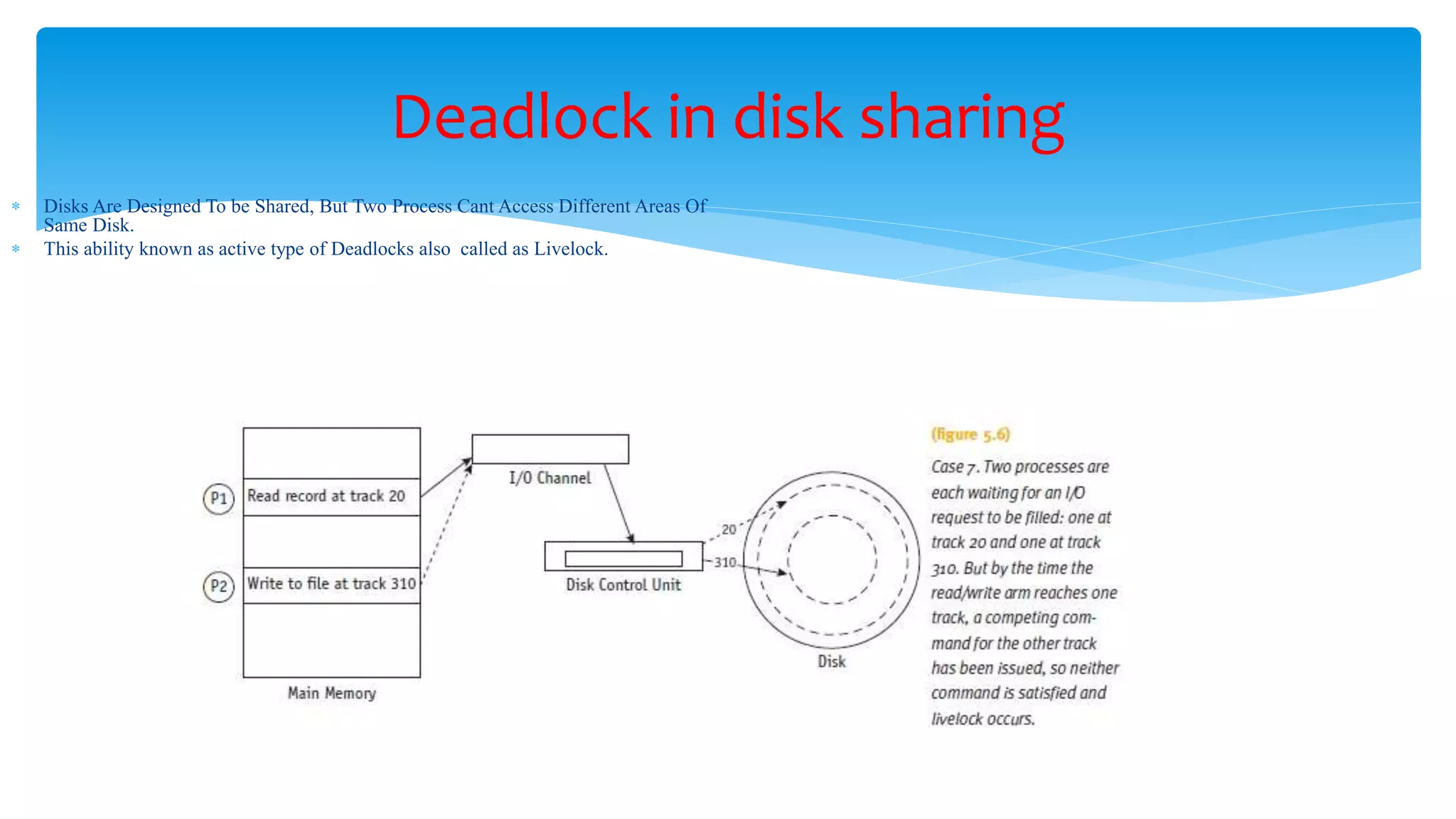

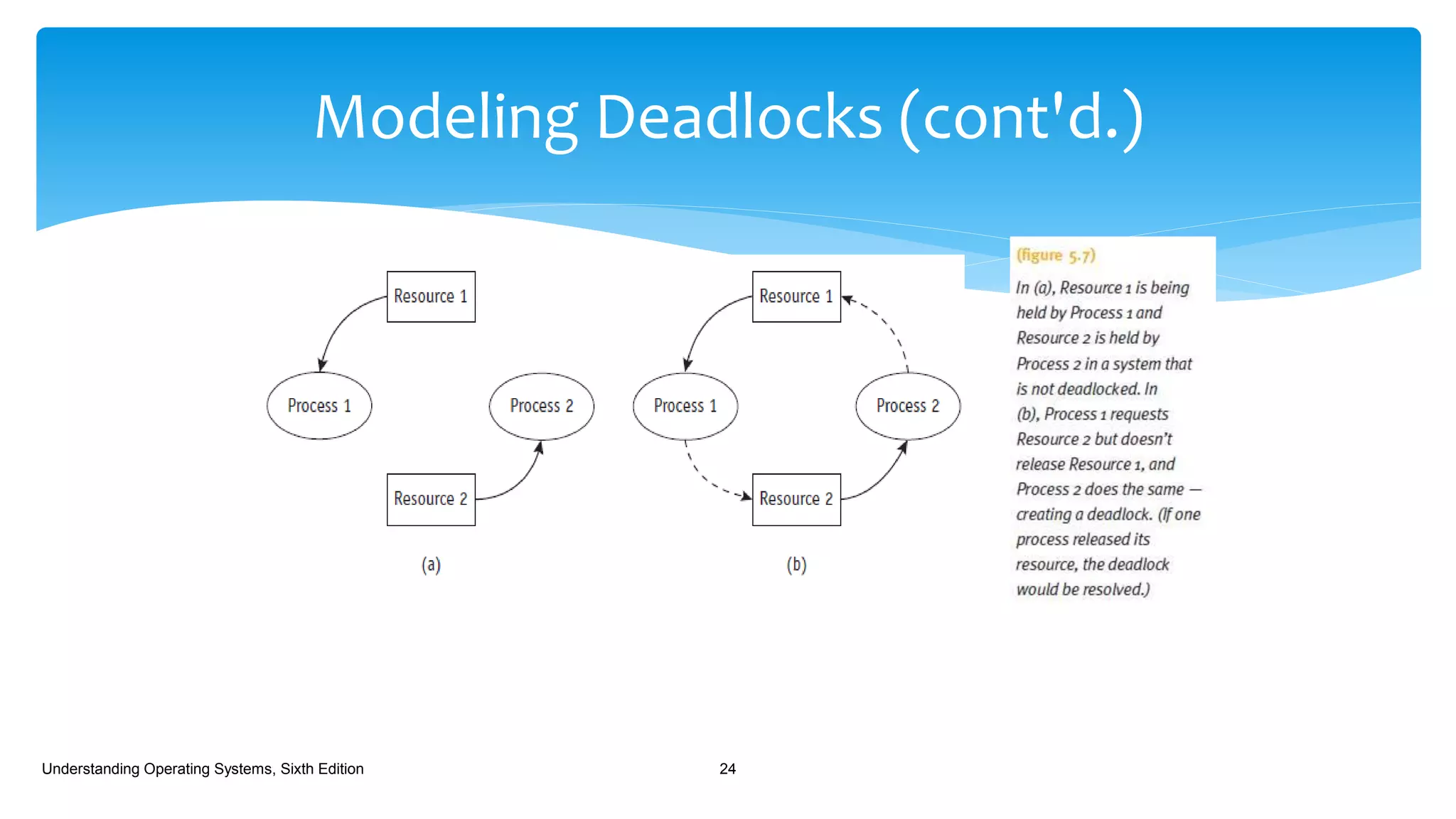

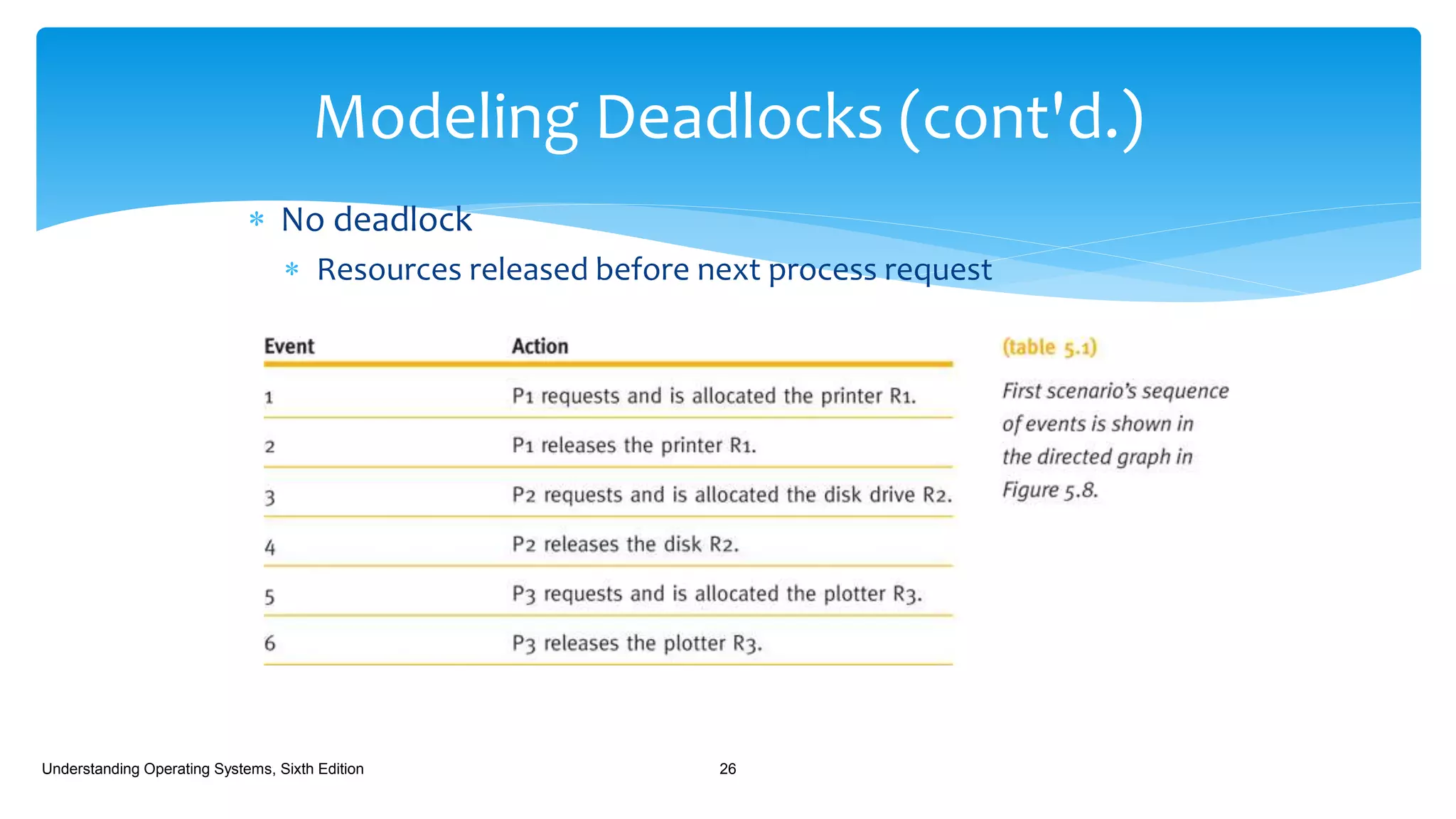

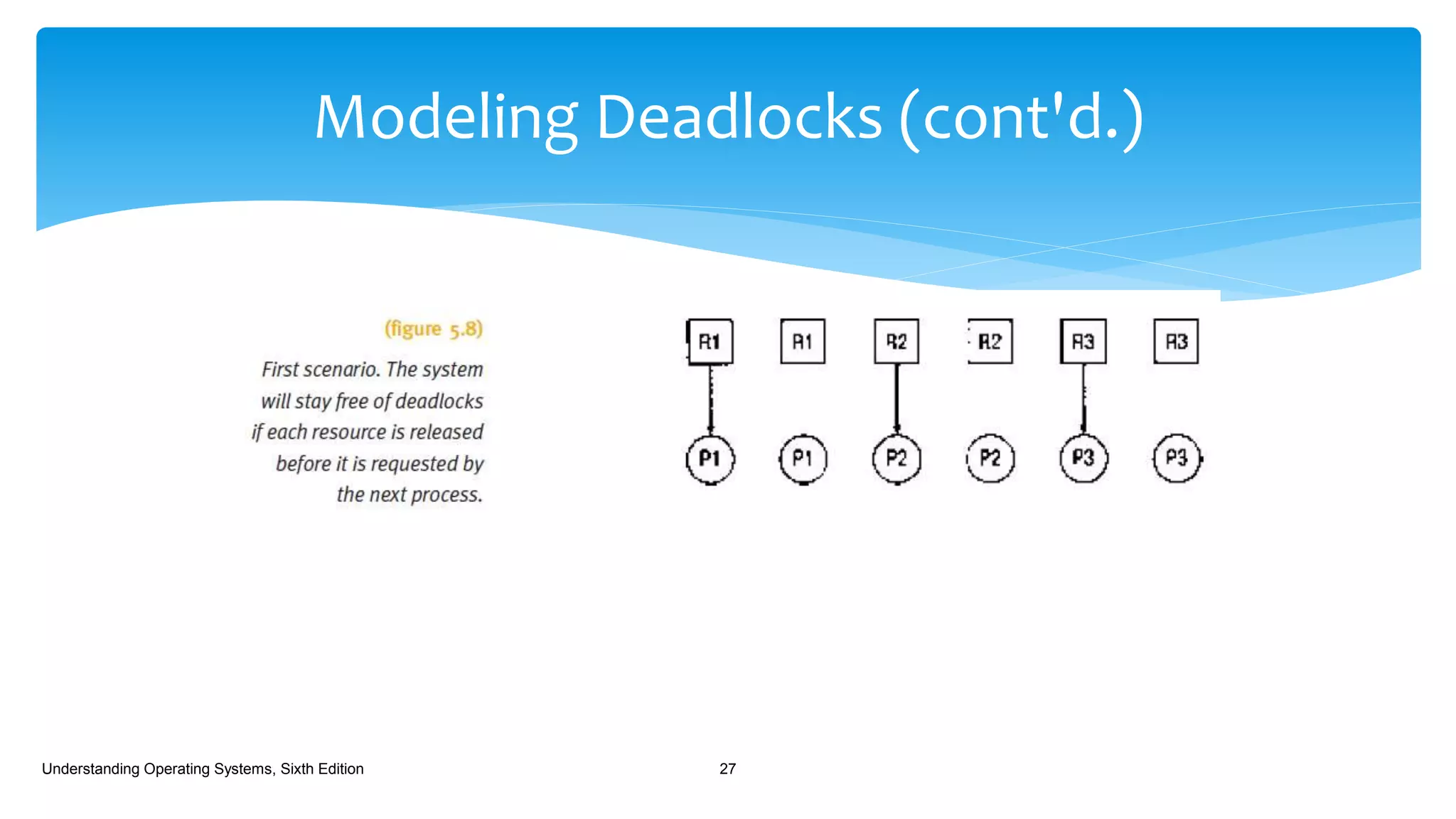

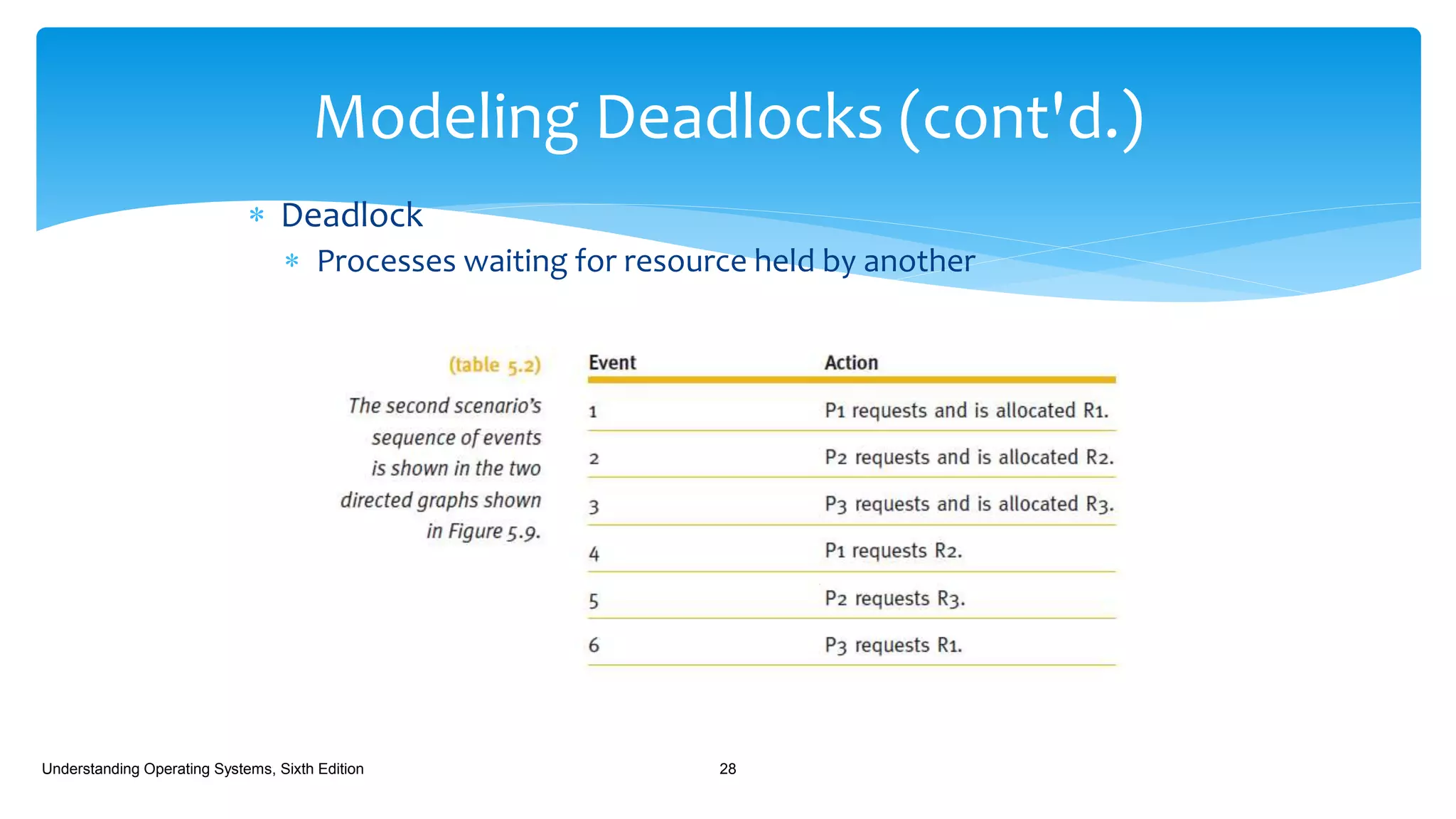

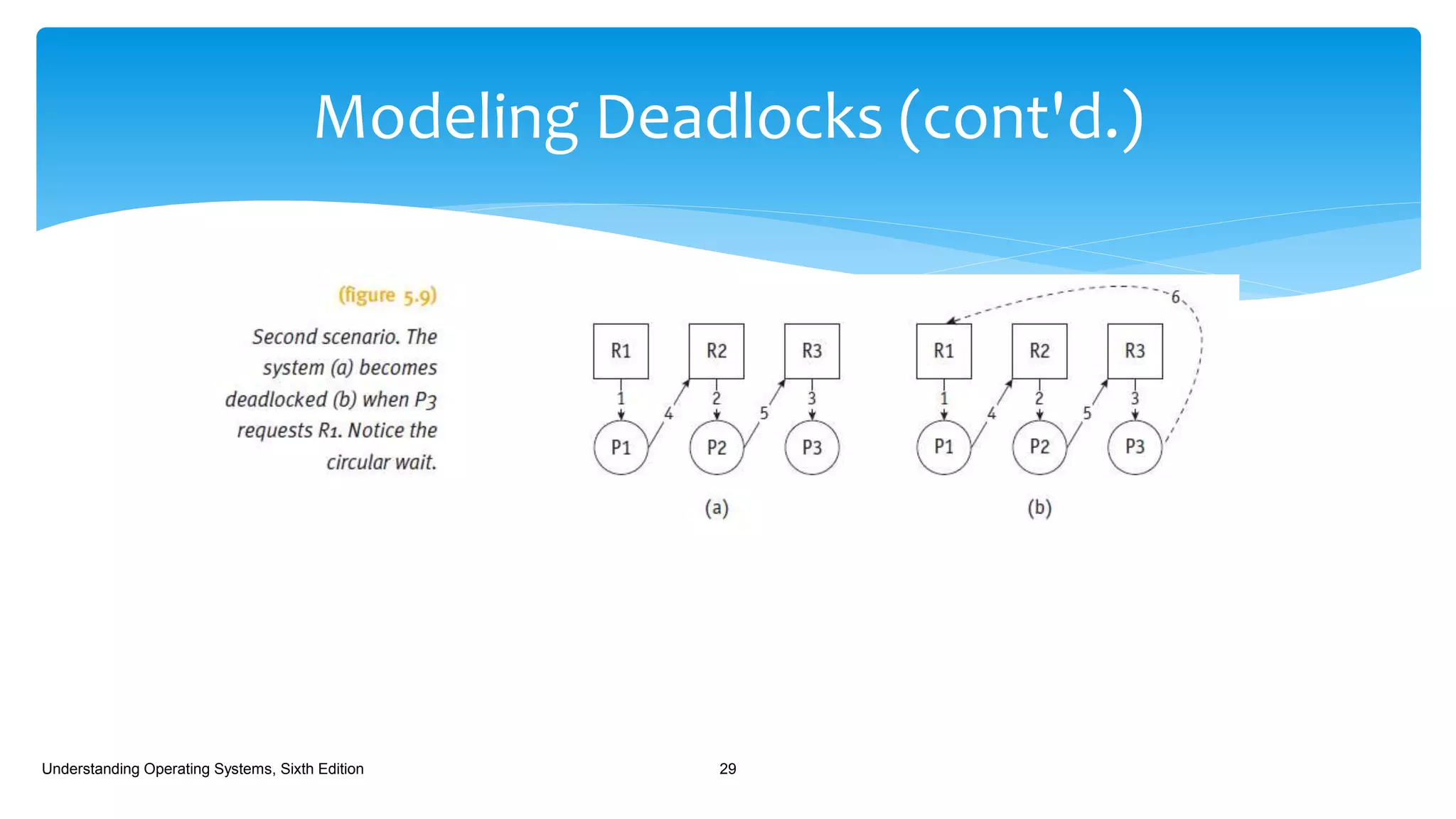

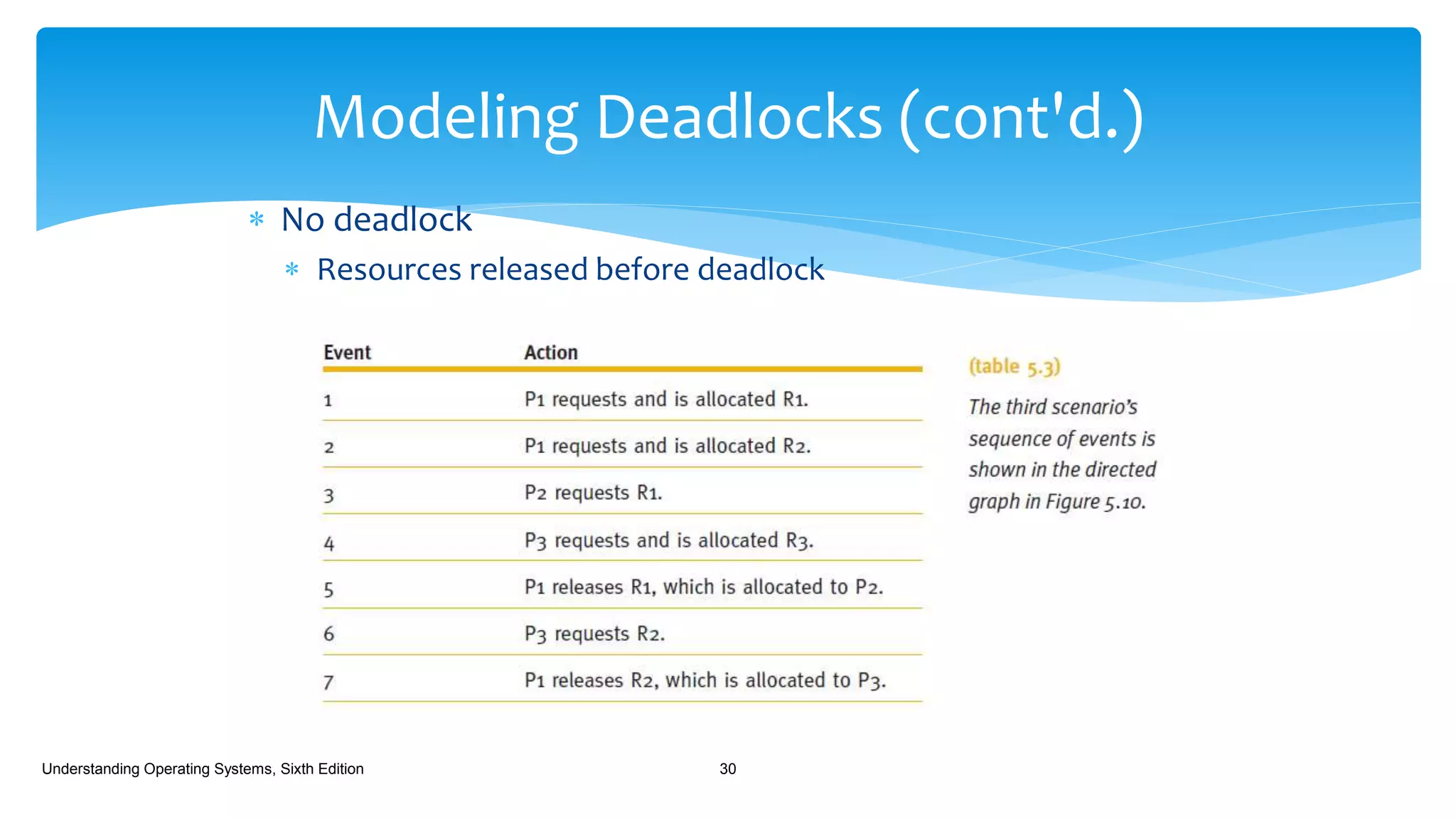

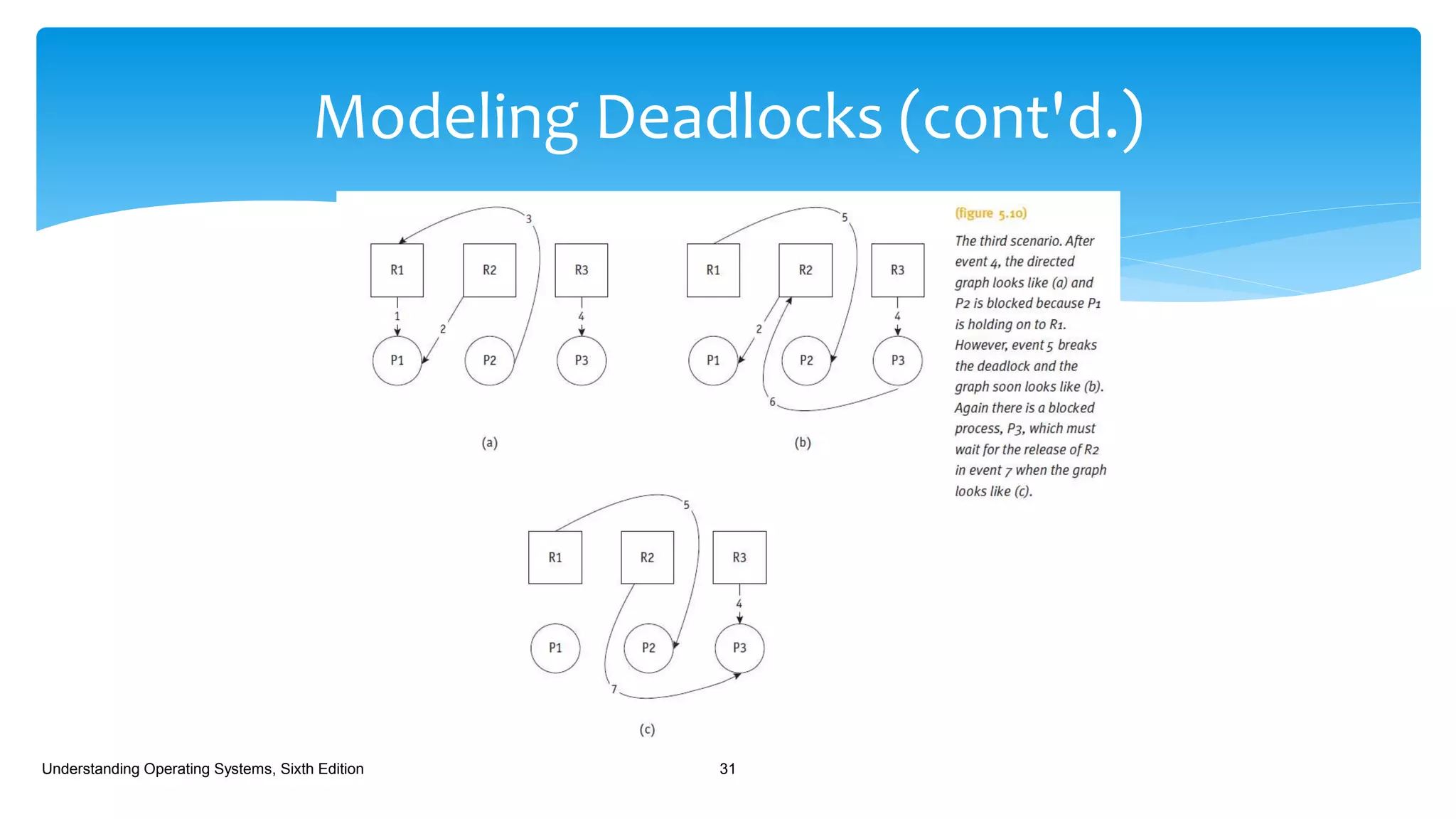

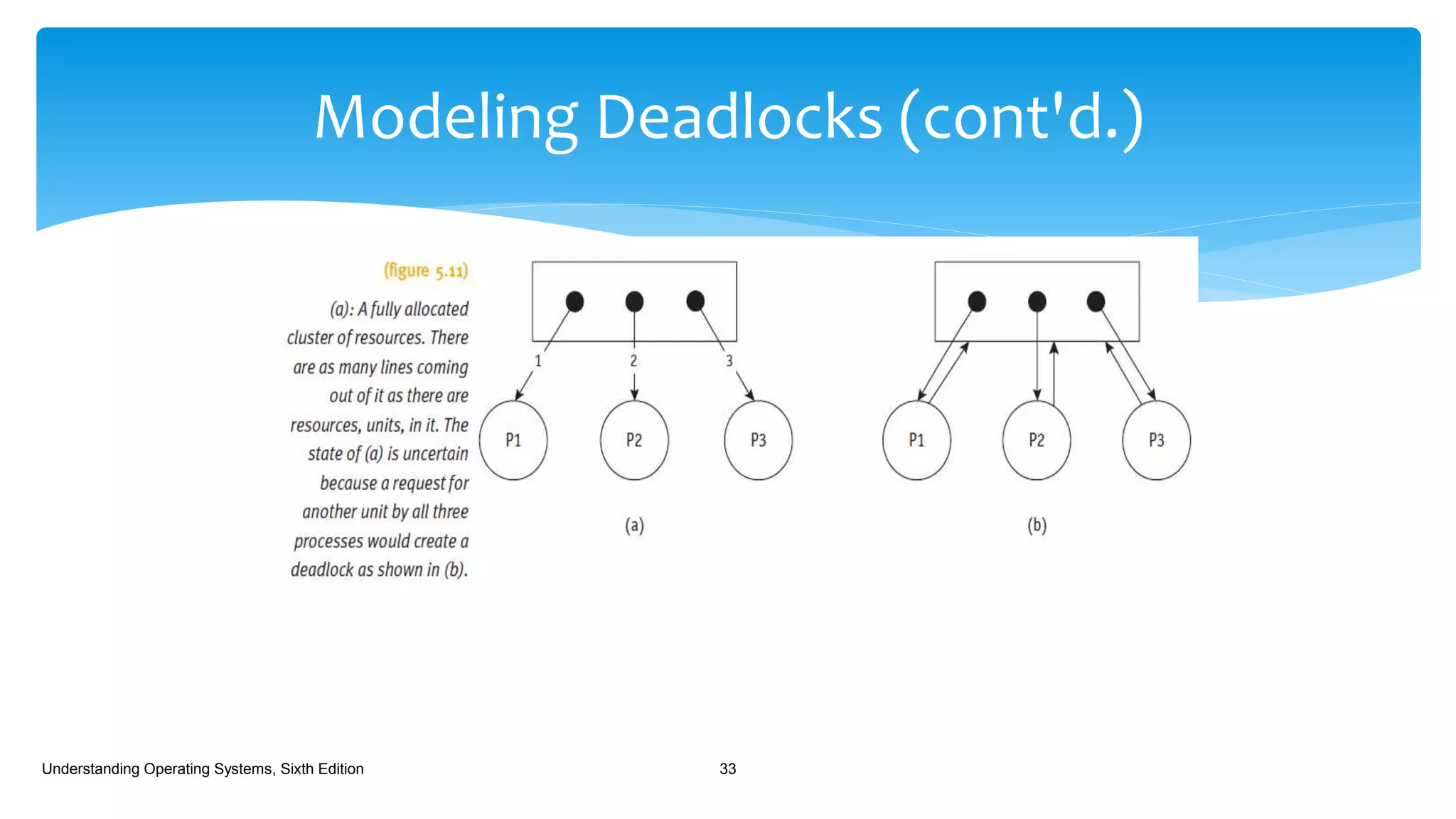

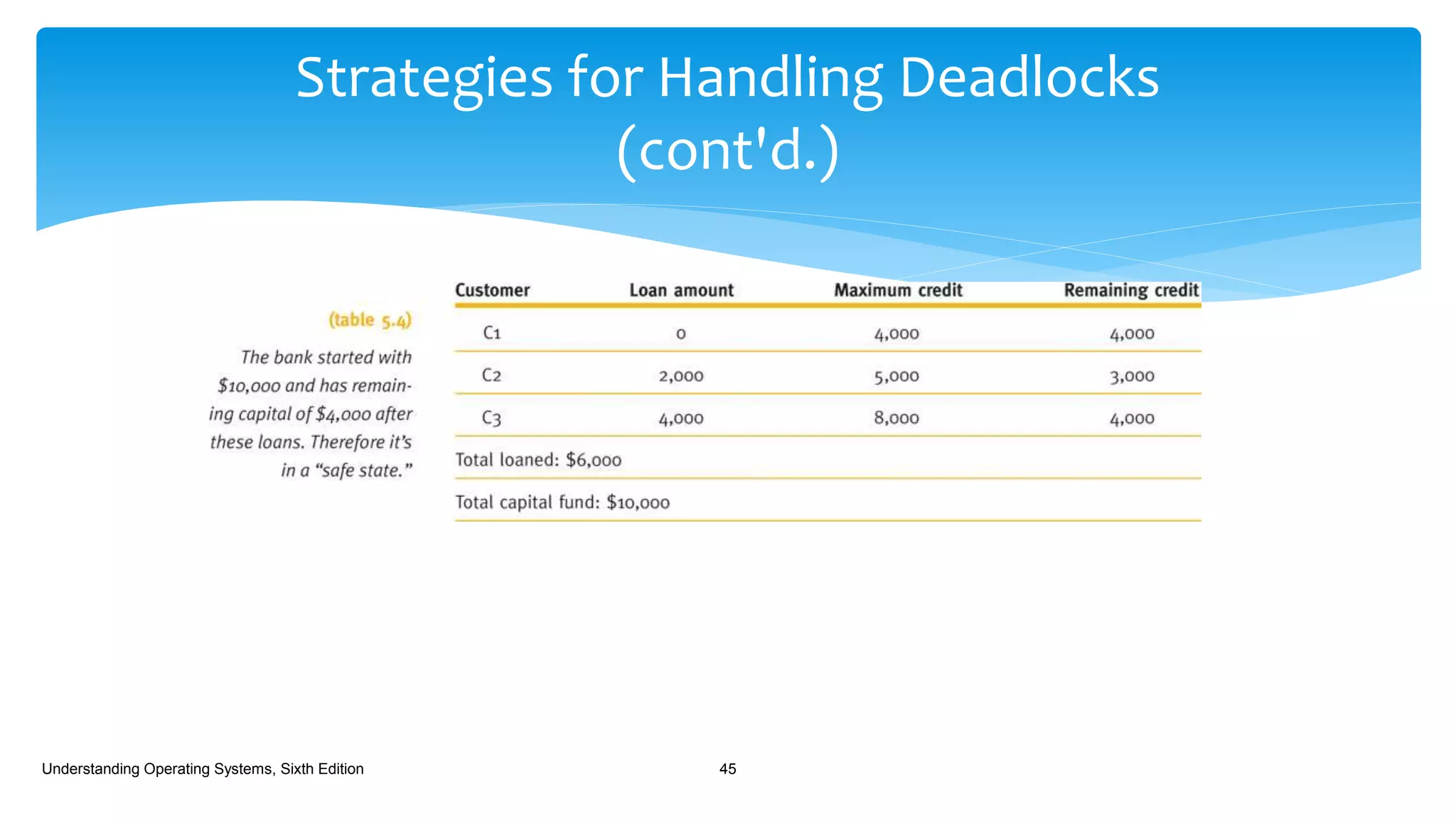

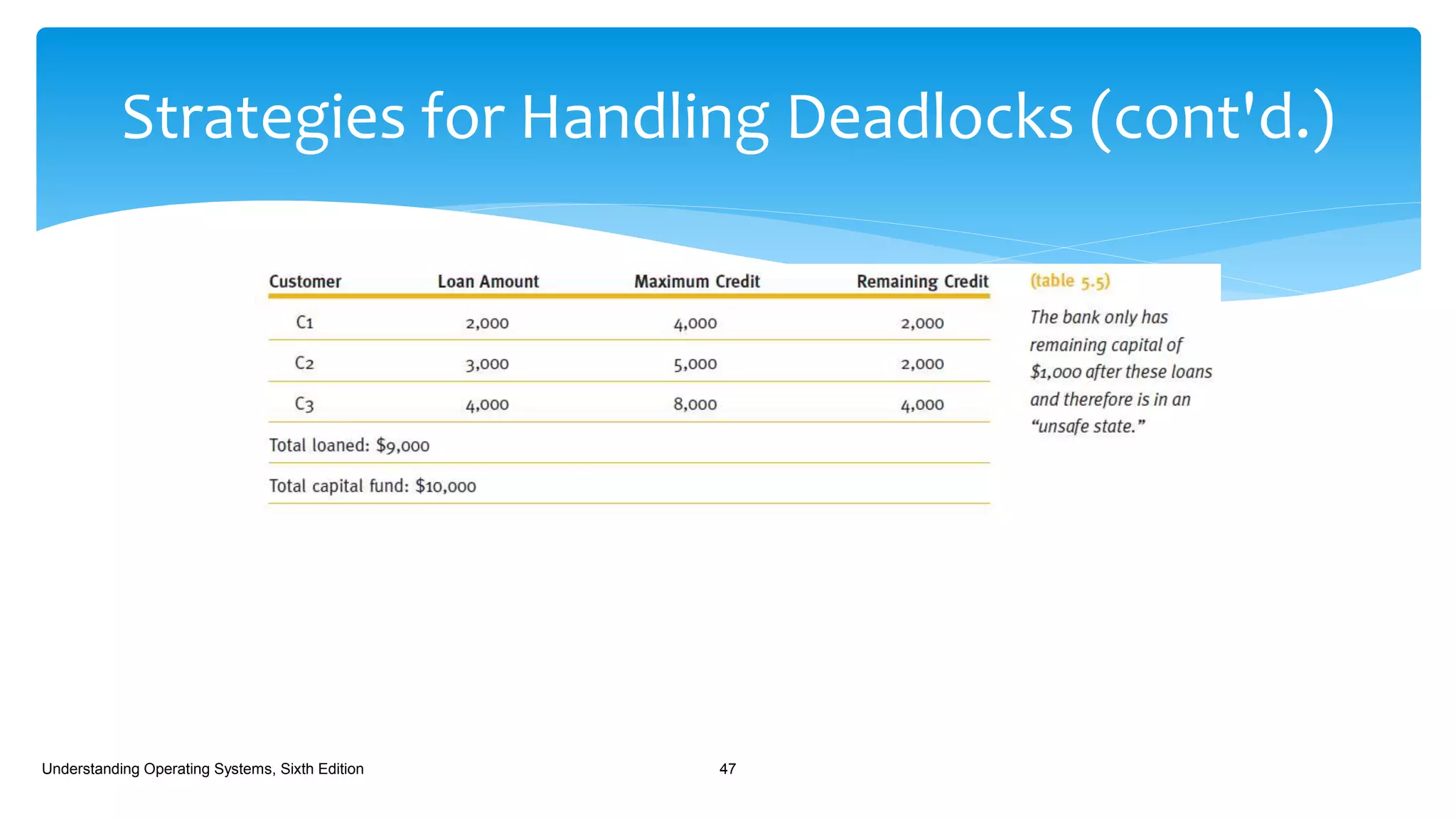

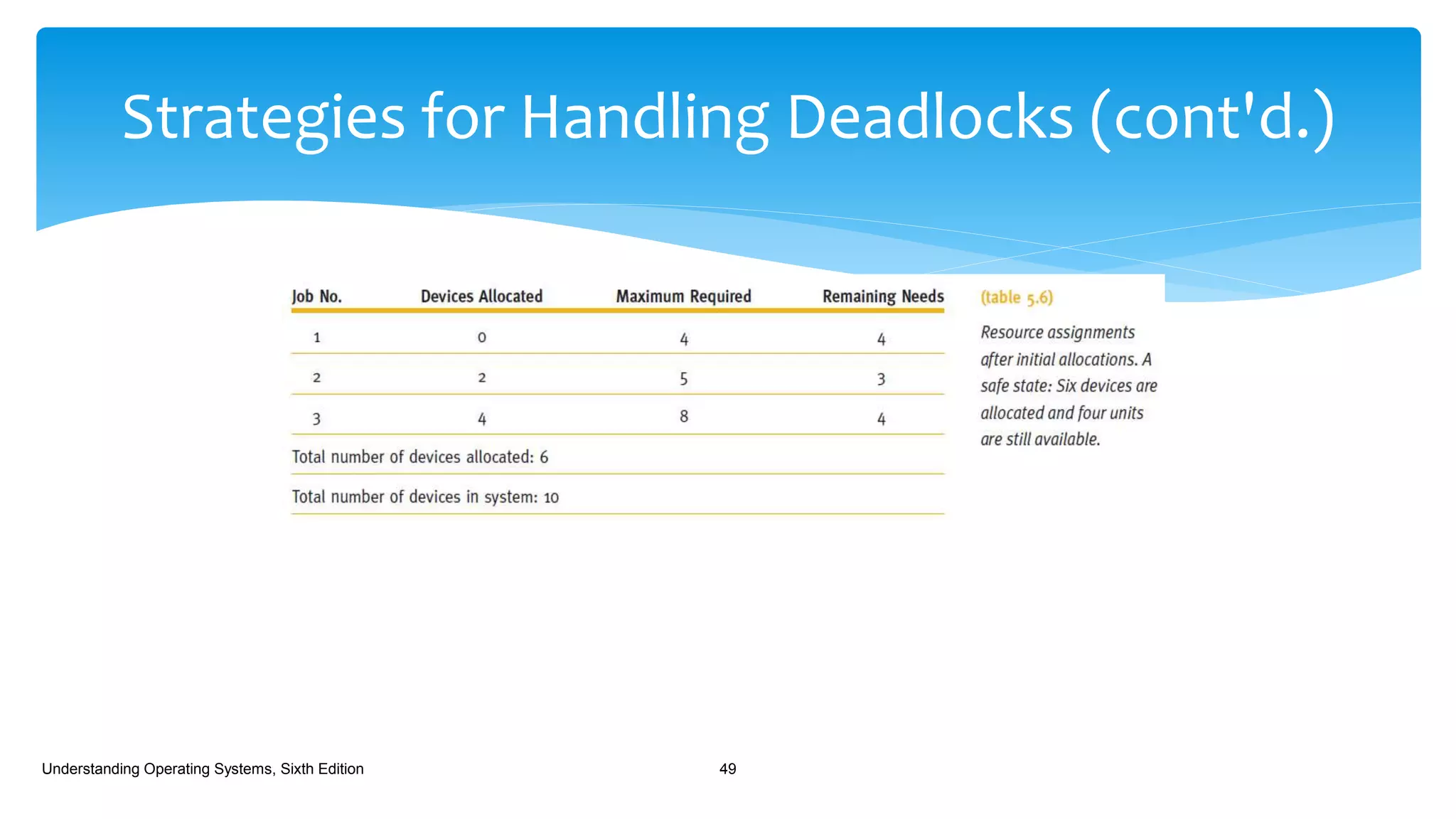

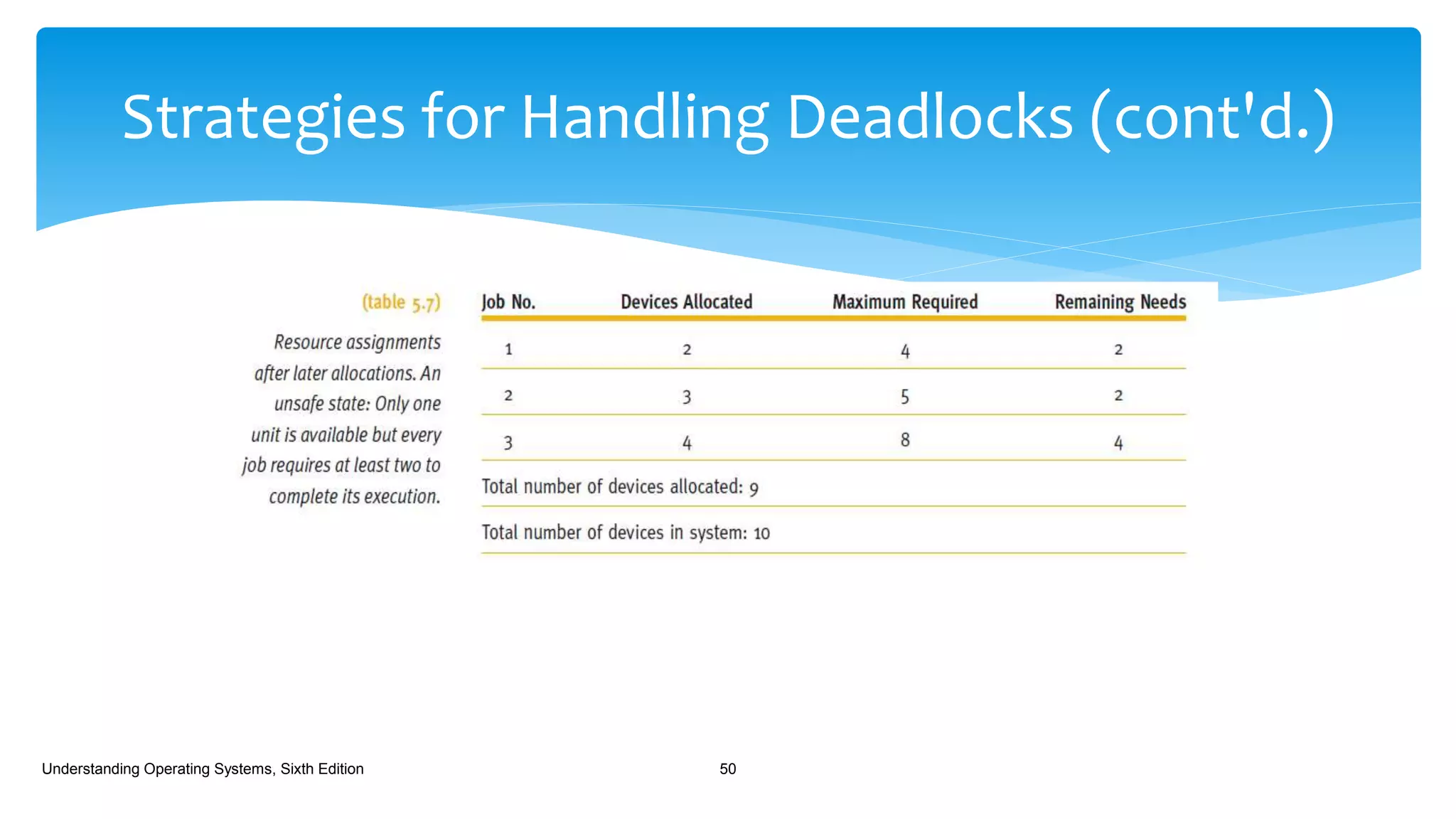

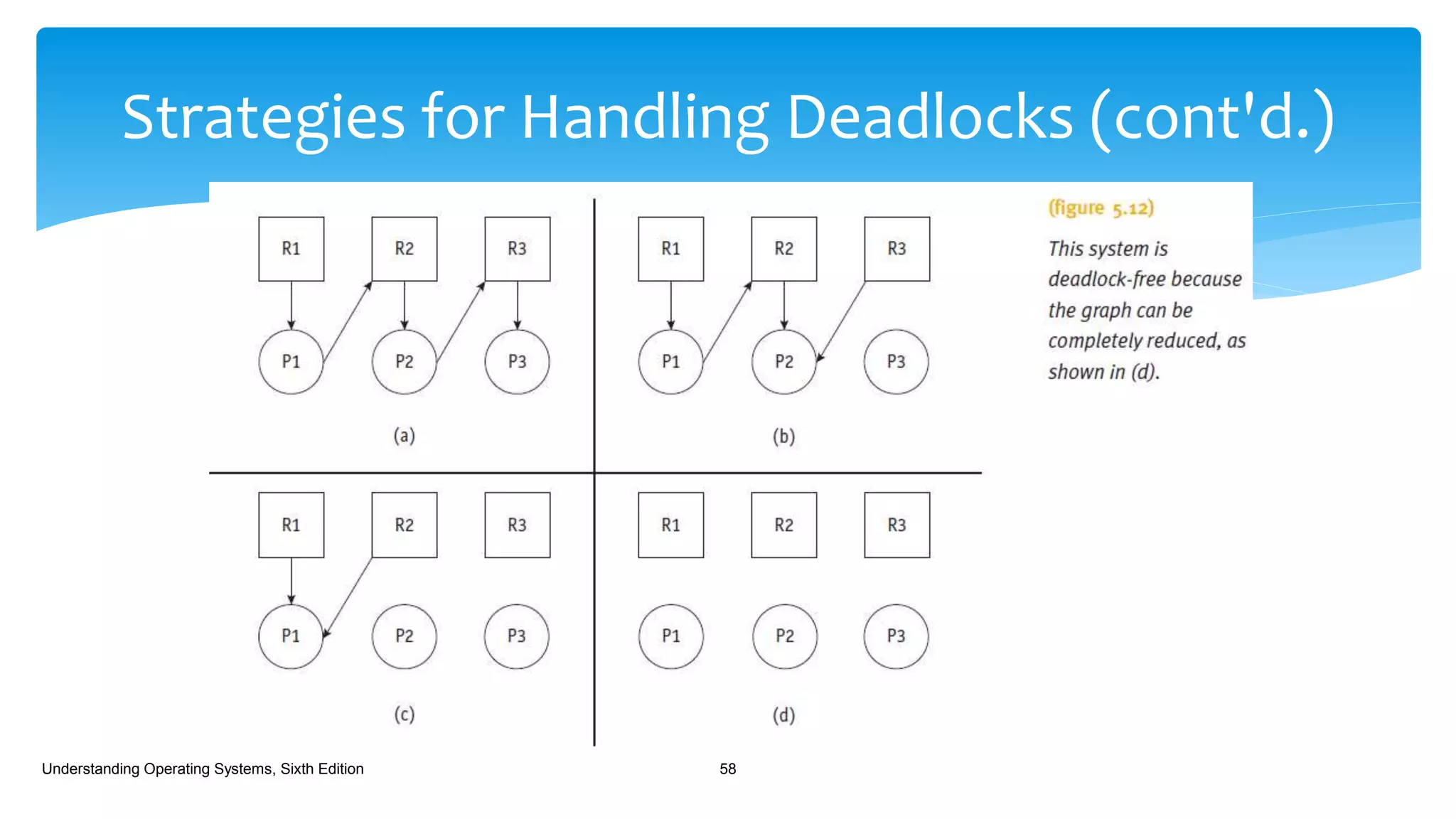

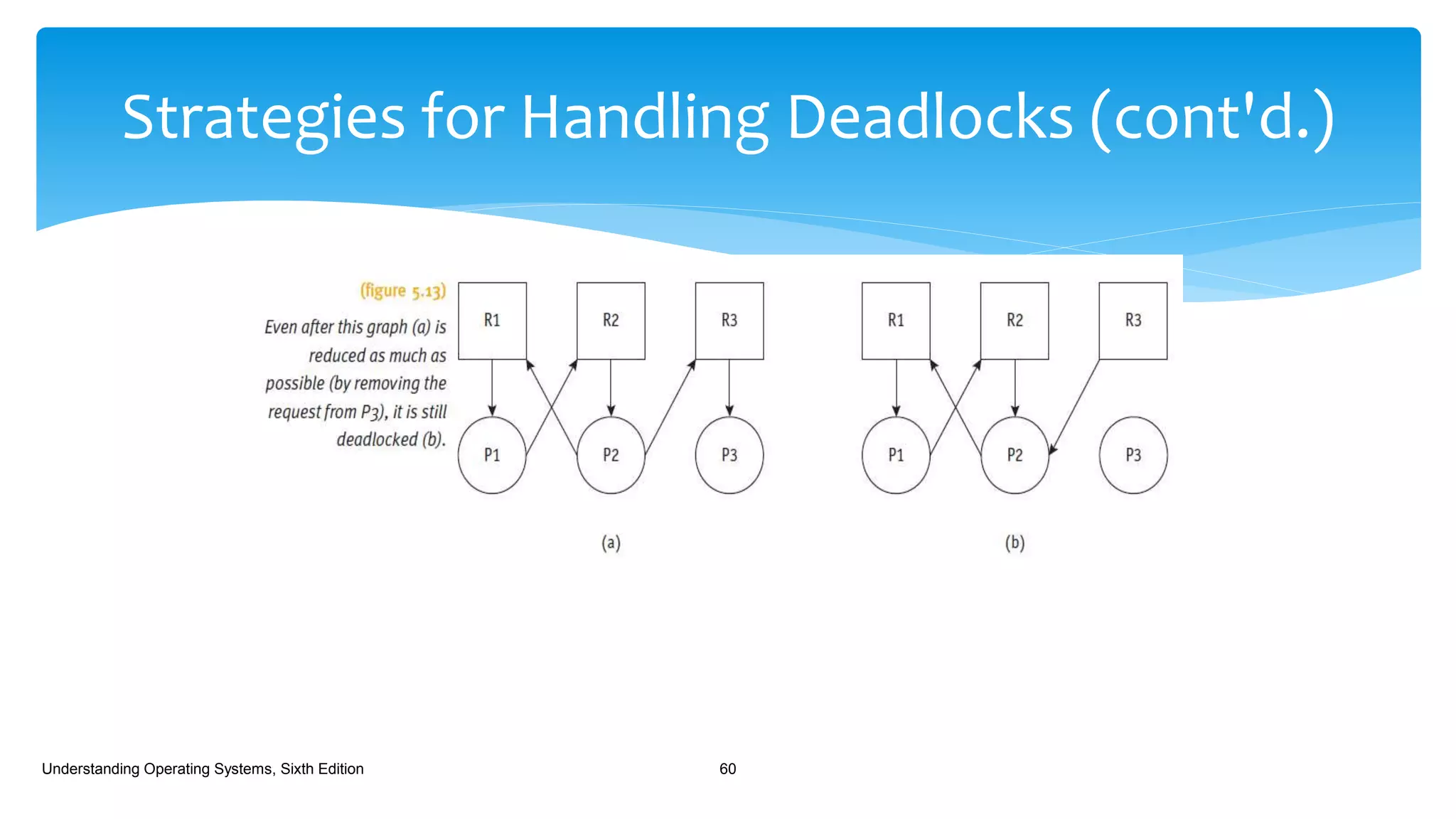

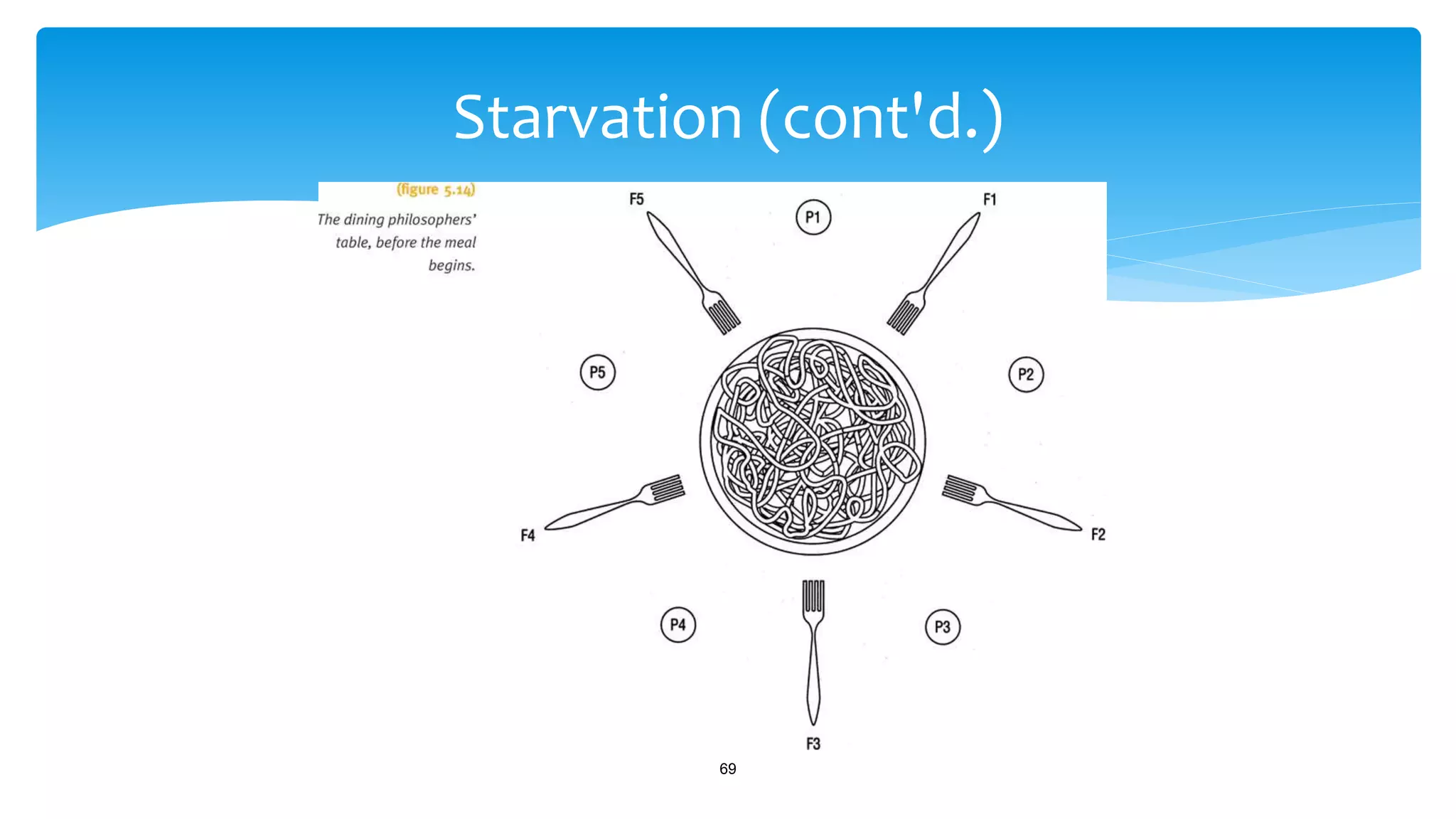

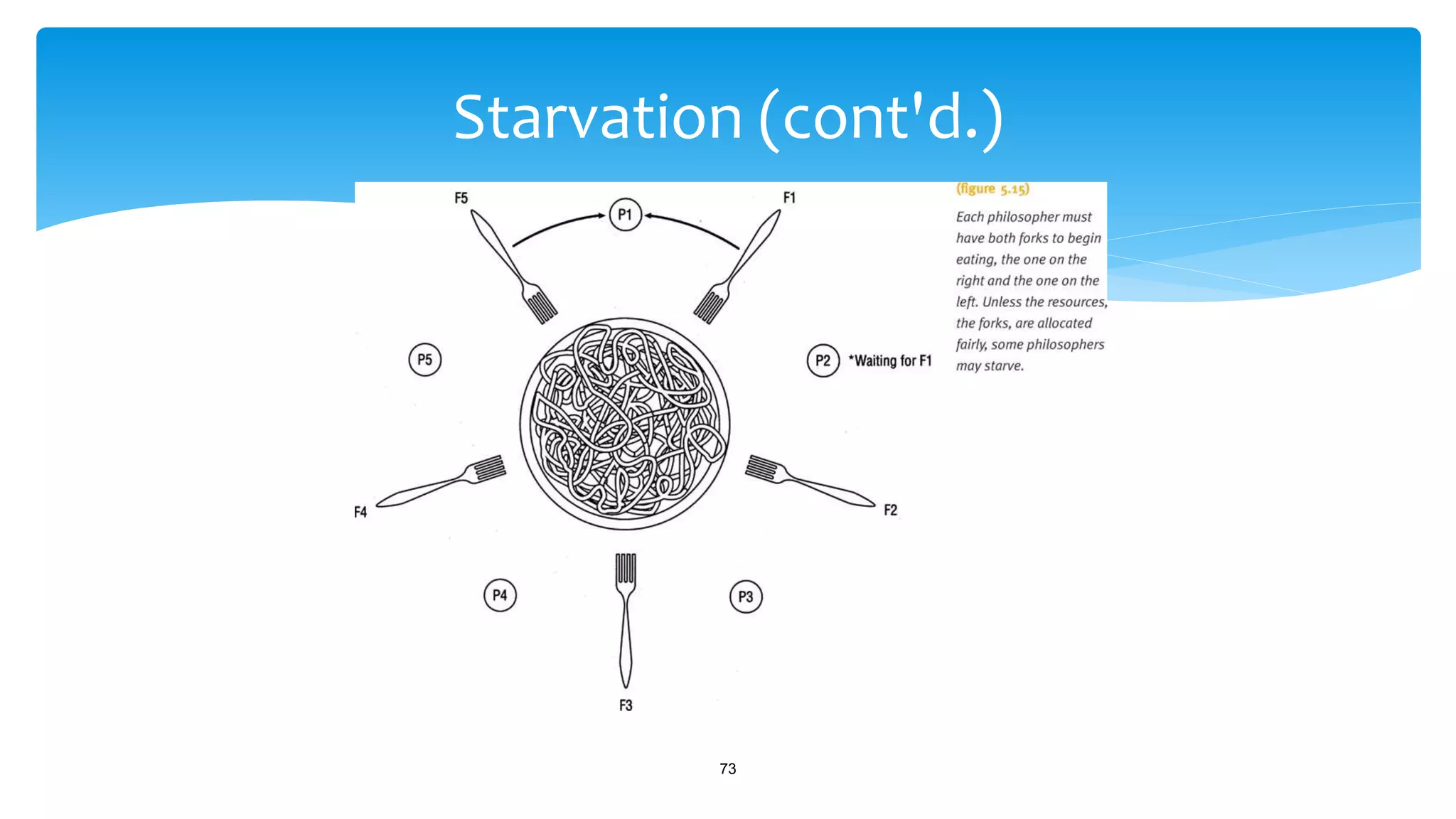

The document discusses process management in operating systems, detailing the cycle of resource requests, usage, and release. It defines deadlock and presents seven different scenarios where deadlocks can occur, including file requests, databases, and dedicated device allocation. Strategies for preventing, avoiding, and detecting deadlocks are also explored, highlighting the complexities and required conditions for deadlock situations.